- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

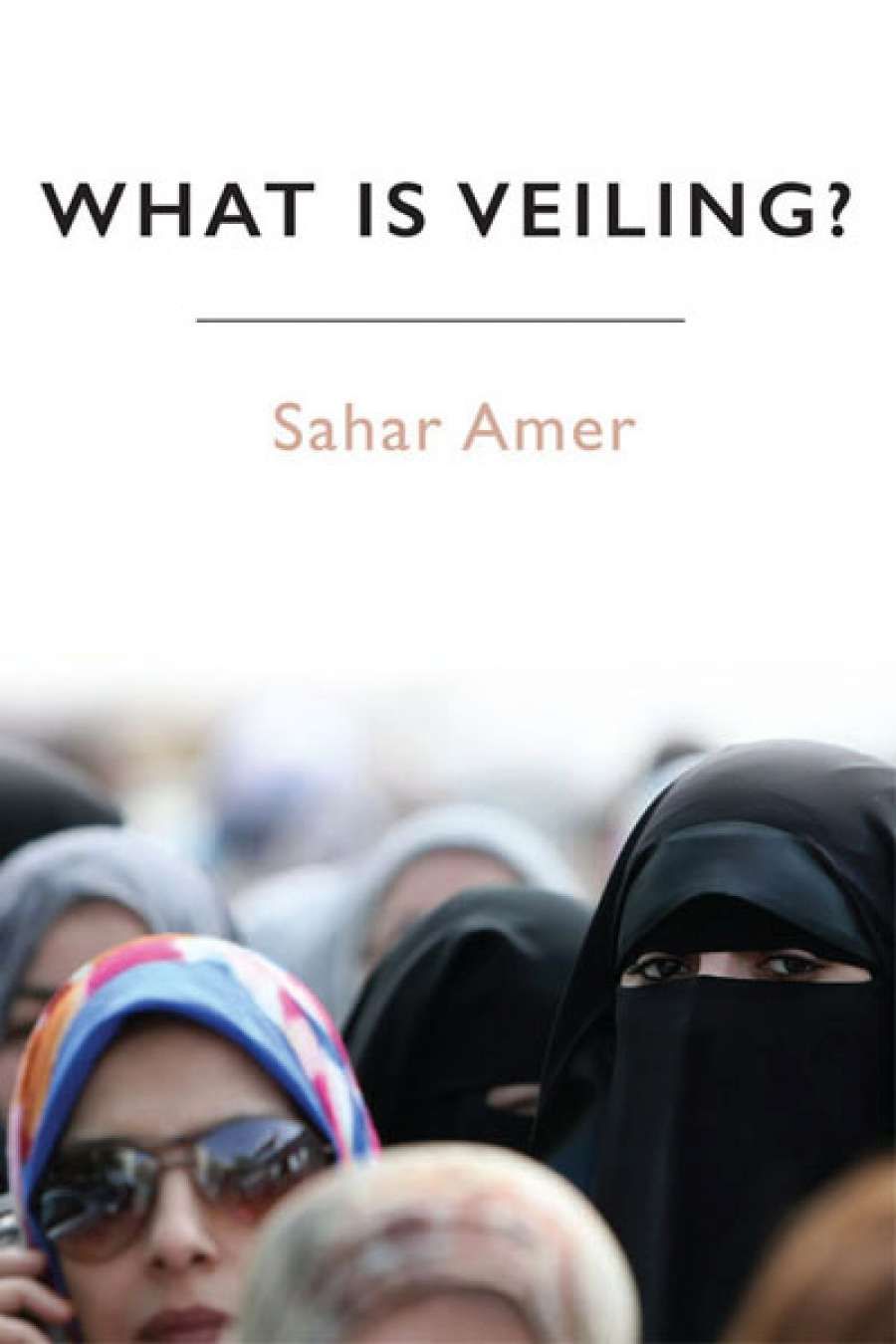

- Custom Article Title: Carolyn D'Cruz reviews 'What is Veiling?' by Sahar Amer

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Veiled views

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a child growing up Catholic in the late 1960s, I wore a black lacy veil over my hair to church every Sunday. After losing my religion sometime in my mid-teens, I had forgotten about this veil wearing until I found myself arguing with far too many people about the ‘burqa ban’. The general vitriol, together with the presumptions many people hold about Muslim women in particular, and Islam more generally, make me wonder how veiling has generated such significance in everyday life, national policy, and foreign affairs.

- Book 1 Title: What is Veiling?

- Book 1 Biblio: Edinburgh University Press, $34.99 pb, 248 pp

In this context, What Is Veiling?, written by Professor Sahar Amer of the University of Sydney, is a welcome contribution to much-needed public education on what the cover flags as one of Islam’s ‘most controversial and misunderstood traditions among both Muslims and non-Muslims’. The first point Amer makes is that ‘Islam did not invent veiling’ and that veiling has been practised by other religions, including Christianity and Judaism. Amer encourages us to ask, ‘How did this piece of clothing become so emotionally and politically charged?’ If we follow her sensitive introduction to practices of veiling over different times, regions, political climates, and religions, we are likely to agree with her simple yet edifying findings: veiling means more than one thing to those who wear them and those who choose not to. Given the variety of veils, it is wrong to reduce them to one type, such as the burqa (among many types of Muslim dress for women, others include: chador, hijab, niqab, and shalwar qamis). The multiplicity of meanings attached to the wearing of veils over different historical, religious, and cultural contexts defies the homogenising forces that perpetuate the reductive meaning assigned to its different forms in public debates today.

It is no easy task to intervene in a debate that has become so wedged into defending or criticising Muslim women who wear different forms of veiling, but Amer manages to move the discussion away from such polemics deftly and elegantly. This three-part book fosters a more critical attitude to the limited positions available: such as secularism vs religion, nationalism vs multiculturalism, feminism vs oppression.

Situating veiling in Islamic sacred texts, as well as in progressive and conservative Muslim politics, Amer shows what ought to be obvious to us all: Islam as a religion and Muslim as an identity are not homogenous. The Qur’an is open to interpretation, subject to multiple translations, irreducible to what it literally says, and its poetic language propels different commentaries on how to live according to its word. The hadith – a collection of texts containing eyewitness reports of what the prophet Muhammad said and did – has few references to Muslim women’s and men’s attire, as does Islamic jurisprudence, which is a translation of the Qur’an and hadith into a practical legal system. Jurisprudence here is not to be confused with the Law of God (sharia), as it often is in Euro-American (and Australian) mainstream media. Along with Muslim progressives, Amer acknowledges how any rendition of the sacred book, Islamic history, and Islamic law will carry its own biases and assumptions, where there can be no definitive word on veiling requirements extracted from core Islamic texts. Furthermore, veiling, she argues, cannot be attributed to religion alone.

Sahar Amer

Sahar Amer

Amer’s attendance to historical and regional detail connects current arguments about veiling as a symbol of gender oppression and the alleged backwardness of Islam as a patriarchal religion to the guise that the European ‘civilising mission’ of nineteenth-century imperialism gave itself, where ‘white men save brown women from brown men’ (Amer curiously misattributes this phrase to Chandra Mohanty instead of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak). Against this ‘civilising mission’, Amer underscores how Muslim women also wore the veil as an act of resistance against colonising powers, showing solidarity with one another. While observing how Orientalist stereotypes of Middle Eastern otherness in nineteenth-century European painting, photographs, postcards, and film are so readily resurrected in contemporary ‘civilising missions’ of military infiltrations in Muslim majority societies today, Amer prompts us to consider how the same stereotypes bolster current justifications for legislating against forms of veiling in countries where Muslims are a minority.

By far the strongest and most novel contribution Amer makes to public debate is the section that weaves the words of Muslim women themselves through present-day cadences of Islamic feminism, hijab poetry, stand-up comedy, and fine arts. Amid the consumerist language of choice, the Muslim fashion industry and birth of the burkini (a blend of burqa and bikini), beauty pageants, and Muslim dolls, Amer demonstrates that the meaning of veiling is far from singular and transparent to the onlooker. As indicated by the linguistic shift in Egypt from muhajjabat (covered women) to mutahajjibat (women who cover), there is a new emphasis on the agency involved in claiming Muslim identity and the choice to veil. Among other terms riding this new wave of women’s agency are ‘hijabistas’, ‘fashionable fundies’ (fundamentalists), ‘makeuphijabs’, and ‘muhajababes’. Following Amina Wadud, Amer is well aware that ‘the hijab of coercion and the hijab of choice look the same’ (emphasis in original). But for those who are so quick to opine about veiling, perhaps the lesson is learning how to listen to those who are most affected by the discussion.

Comments powered by CComment