- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

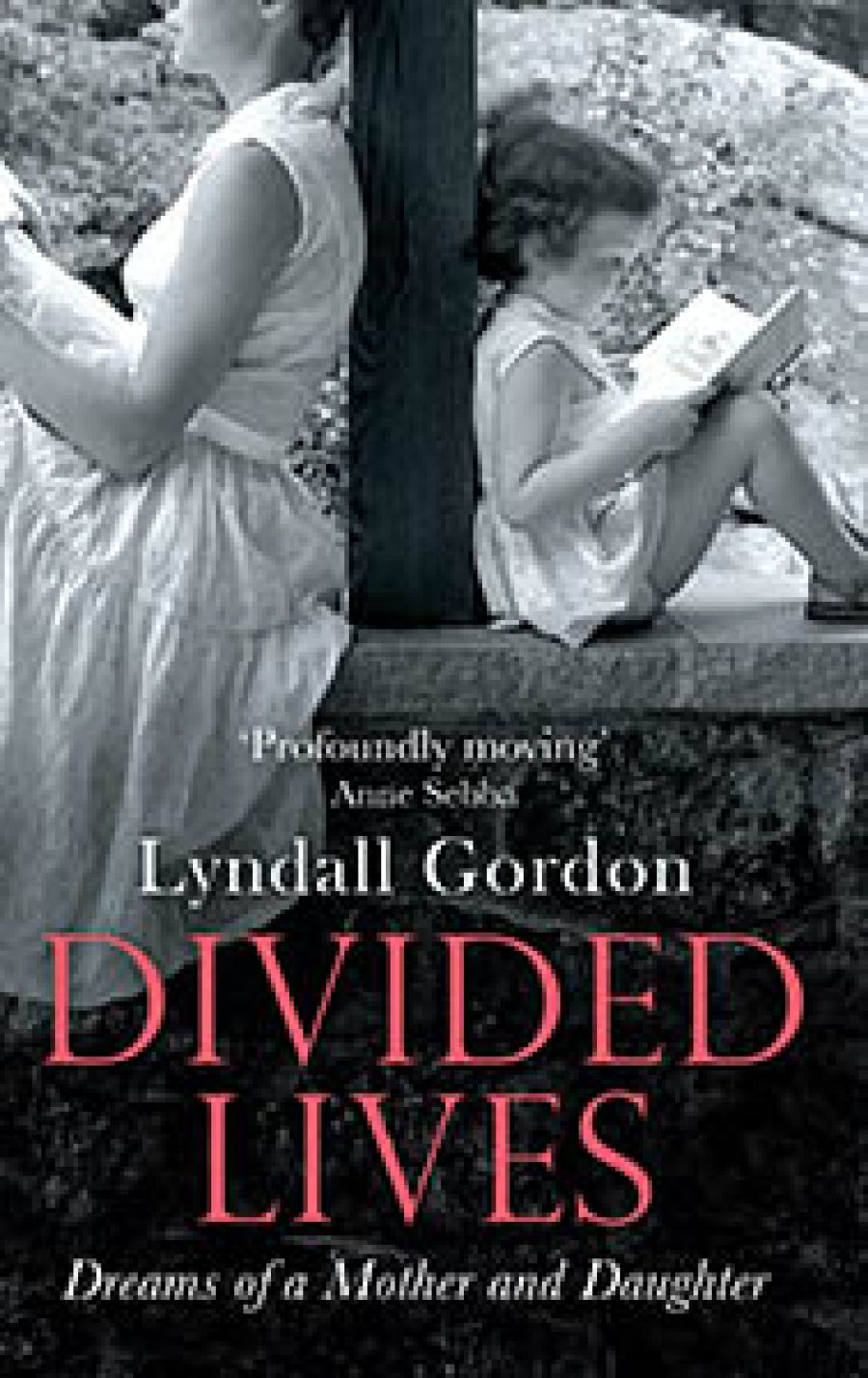

- Custom Article Title: Dorothy Driver reviews 'Divided Lives: Dreams of a mother and a daughter' by Lyndall Gordon

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The biographer and her mother as secret sharers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Two thirds of the way into Lyndall Gordon’s part memoir, part maternal biography, there is an episode of profound risk to the self. At the age of twenty-four, having recently moved from Cape Town to New York, Gordon is being treated for post-partum depression. This is 1966. Electro-convulsive therapy seems not to have helped, and her psychiatrist is urging longer-term treatment in an asylum in order to turn her – so it seems to Gordon – into the self-sacrificing wife and mother her own mother had wished her to be. Her husband, who has hitherto supported Dr Kay, makes a sudden turn. ‘Do something with your life … I’ve always thought you could write biography.’

- Book 1 Title: Divided Lives

- Book 1 Subtitle: Dreams of a mother and a daughter

- Book 1 Biblio: Virago, $35 pb, 328 pp

Although there is more shock treatment, and concomitant memory loss, Gordon is by 1968 enrolled for doctoral study at Columbia University. A decade later she has published Eliot’s Early Years, the first of the literary biographies that will win her a scholarly reputation. By 1984 she has produced Virginia Woolf: A Writer’s Life and has a permanent position at St Hilda’s College, Oxford. There are no further mental breakdowns.

Four more biographies follow: of Charlotte Brontë (1994), Henry James (1999), Mary Wollstonecraft (2005), and Emily Dickinson (2010). She writes a second Eliot book, later amalgamated with the first to form T. S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life (1999). She also produces her first experiment in memoir cum biography, Shared Lives (1992).

Her new book, Divided Lives, covers the same time period as Shared Lives, and adopts the same generic strategy, but the angle is different. Whereas, in the earlier book, female friends helped shape her life, Divided Lives focuses on her mother’s acts of shaping, but also, as the title suggests, on Gordon’s own acts of resistance. Her survival and ultimate flowering required hard work and pluck, as well as the intervention of a suitor who, as she says, valued intellectual ‘flair’ in women above good looks. Overall, the book details a young woman’s shift of allegiance from mother to husband, her subsequent assertion of autonomy while still remaining a loving mother and wife, and the forging of her career.

Lyndall Gordon, née Press, was born in South Africa in 1941, of Lithuanian Jewish descent. Judaism looms large in her formation. A motif common to both memoir-biographies is the belatedness of feminism for this generation of young Jewish women, destined first and foremost to become mothers and wives. Gordon recalls the impact of the first Women’s Liberation meeting she attended in 1970, when she heard Kate Millett give voice to her own nascent feminism. This may have been hitherto ‘unvoiced’ in herself, as she puts it, but what Divided Lives vividly shows is the complex process of its generation, with her mother both nurturing and curbing it.

Lyndall Gordon (photograph by Jerry Bauer)

Lyndall Gordon (photograph by Jerry Bauer)

Herself fraught with self-division, Rhoda Press gave contradictory directions to an admiring but anxiously watchful daughter. Rhoda was well-read and imaginative, and driven by a certain proto-feminist energy, running reading groups and doing voluntary community work. She also suffered from epilepsy, an illness that, for Lyndall, seemed to add a visionary dimension to her mother’s imaginative life. When Lyndall was ten, Rhoda left their Cape Town home to enrol in a literary course at London’s Goldsmith’s College. For six months she abandoned her domestic duties. She also became involved in – but kept pulling back from – a love affair (mostly epistolary) with a biblical scholar and Zionist, a man whom she felt to be her intellectual soulmate, quite unlike Lyndall’s father, a ‘breezy’ lawyer and part-time radio sports commentator. For her school-leaving daughter, she plotted what she no doubt saw as a more straightforward course: Lyndall would go to Israel, live on a kibbutz, learn Hebrew, and study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; then, primarily through motherhood, she would help give body to the myth of the Promised Land.

As a schoolgirl, Lyndall had already joined Habonim, a Zionist youth organisation. But her first-hand encounter with Israelis and the ‘apartness’ they forced on Arabs, obliterating their past ‘by the ideology of the Return’, was so disillusioning that the first major divide appeared between her mother and herself. Israeli policies were too much like South Africa’s, as were Israeli habits of male dominance and female submission.

Rhoda refused to accept the true reasons for Lyndall’s abandoning Israel, accusing her of being incapable of forgoing the luxury and ease that Apartheid allowed whites. In turn, Lyndall was critical of her mother’s regard for appearances and her failure to distance herself from the crass materialism of their friends. In her mother’s high-handed treatment of black servants, she saw her proclaimed political stance belied. Neither Lyndall nor her husband could stomach South Africa: they moved to New York, then she to Oxford, with their first child. Her husband would follow. ‘Ahead of his time’, he approved of the way she prioritised her career.

Gordon represents a complex mother–daughter sharing that works against the differences and the ultimate parting of their ways. This is sometimes manifested as an uncanny doubling, Lyndall’s shock treatment, for example, echoing Rhoda’s epilepsy. This doubling exemplifies Lyndall’s view of herself as a ‘secret sharer’, after the story by Joseph Conrad. But the sharing took another direction as well, as if the daughter was the mother’s other in more positive, assertive ways. This was in part due to the unusual range of roles and responsibilities Rhoda required of her. Sometimes Lyndall had to serve as her mother’s carer; sometimes she felt like her sister, hearing intimacies well beyond a child’s normal experience. Both child and confidante, both carer and cared-for, she was also both pupil and colleague: she learned about literature from her and, for a period, with her, for they enrolled as university students at the same time.

Taking her mother’s lead, Gordon rejects the notion, popular in her day, of ‘the death of the author’ – a notion adopted from Roland Barthes and largely misunderstood. In fact, not unlike Barthes, Gordon’s book confirms in multiple ways the writer’s self-creation through the act of writing. ‘Life-writing,’ as she puts it, ‘demands that we come to know ourselves through our subject.’

Particularly interesting in this regard is Gordon’s wealth of allusions to the writers whose lives shape hers and whose ‘lives’ she has herself entered and shaped. The critical insights that underlie the biographies (on one crucial occasion attributed to her mother), together with her mastery of the documentary material, explain her high reputation in the field. The methodology of both this and the earlier memoir-biography (shared lives, divided lives) is, by and large, the methodology of the literary biographies too: Gordon places writers in a meticulously researched familial and social milieu, closely examining how their most private lives are shaped by these relations. Divided Lives also suggests a process of self-creation through reading. Early in her life, for instance, Lyndall learns from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre an honourable self-identification as a Plain Jane.

Some of the darker and more poignant of Gordon’s allusions are – via Dante, T.S. Eliot, Conrad, and Virgil – to an underworld which we can read as the purgatories she herself has had to pass through to become the teacher, mother, wife, and writer she is: Apartheid South Africa, Israel, her breakdown, and, of course, her mother’s grip (‘Easy is the descent to Avernus, but to recall the step and pass out to the upper air, this is the undertaking, this the task – hic opus, hic labor est’).

Comments powered by CComment