- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

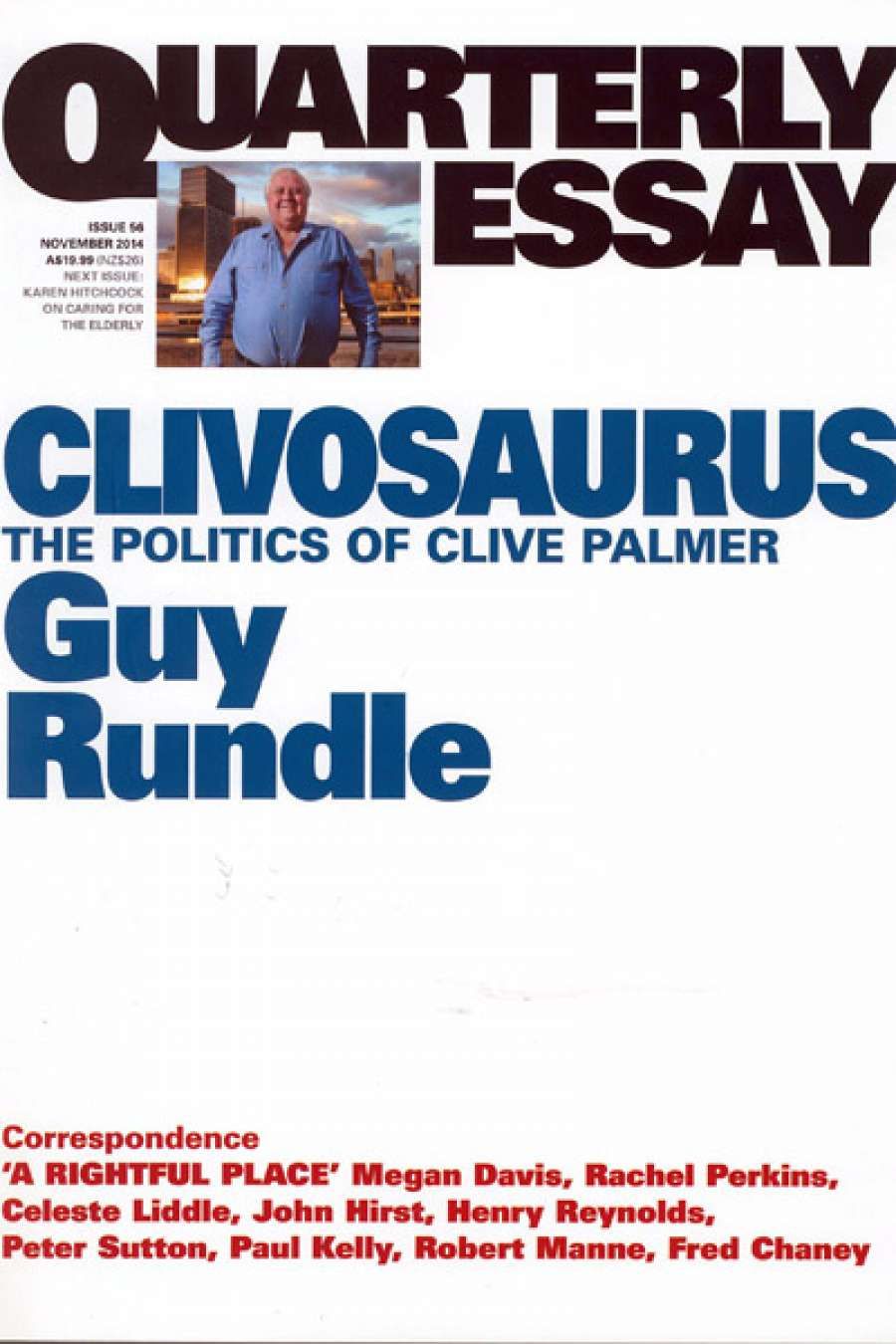

- Custom Article Title: Shane Carmody reviews 'Clivosaurus' Guy Rundle

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Who is Clive?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Guy Rundle ends his engrossing account of Clive Palmer with a disclaimer: ‘Knowing Clive, he will contradict everything asserted in this essay in the two weeks between its going to press and hitting the bookstands.’ Since the publication of this essay, Palmer has not contradicted the assertions of the essay, but his party has been challenged. Senator Jacqui Lambie has resigned from the Palmer United Party. At the November Victorian election, preference deals led to the election of micro parties to the Upper House, without a Palmer United Party member.

- Book 1 Title: Clivosaurus

- Book 1 Subtitle: The politics of Clive Palmer (Quarterly Essay 56)

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc, $19.95 pb, 116 pp

Rundle seeks to explain the origins of Palmer’s moral seriousness. The section dealing with his childhood and early career is fascinating. Rundle reveals a likeable, even admirable Clive Palmer, though he qualifies this after quoting some undistinguished poetry published by Palmer in 1981. One piece celebrates apartheid activist Steve Biko. Rundle reminds us that it appeared at the height of Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s power, when Palmer ‘was a major player in a party running a government whose cops showed no compulsion about cracking open black heads for no other reason than they were black’.

Rundle expands on the influences in Palmer’s life by examining the long shadow of Queensland agrarian populist politics, with its singularity, racism, religiosity, and short-lived parties. Pauline Hanson, Bob Katter, and the young Barnaby Joyce are all given as recent examples. For the most part, their policies and prejudices have supported the conservative political establishment. Joyce is now in the Cabinet as agriculture minister, and the xenophobic basis of Australia’s current immigration régime has its modern roots in the veneer of respectability afforded Hanson by John Howard.

Palmer does not conform to this model. He stands in resolute opposition to the policies of the Abbott government designed to undo the social compact that has defined Australia. Palmer opposes university deregulation, Medicare co-payments, and severe new policies towards the unemployed. His stance on refugees is far to the left of either major party, and his position on the Carbon Tax, the Renewable Energy Target, and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation has confounded a government convinced that a reputed billionaire mining-magnate would support them, if only from self-interest. His social conscience, in Rundle’s view, is due to his Catholicism, and his position is much closer to traditional Catholic social teaching than is the case with Tony Abbott and his predominantly Catholic frontbench.

It is true that Palmer spent millions in achieving his power base, but in this he is not unusual. Palmer won his seat in a conventional preference contest by splitting the conservative vote. His real power is in the Senate and this was largely won through a manipulation of the proportional preferential system that beggars belief. Rundle is appalled by the way this was achieved, and calls for reform, but he also applauds the fact that the government must now negotiate on each and every bill in order to have a majority.

This is an apparent contradiction: Rundle rejects the cause (preference manipulation) while welcoming the effect (more debate). In fact it betrays his deeper disregard for the official opposition. In Rundle’s view free-market ideology is as deeply entrenched in the Labor Party as it is among the Liberals, and he suggests Labor has offered meek resistance to changes like university deregulation, since it essentially agrees with it and in government would only slightly modify this and other policies. Compared to a compromised Labor Party, Palmer, for all his complexity, appears resolute and principled, a man of moral purpose. Reflecting on Palmer’s appearance with Al Gore, Rundle marks this as the point at which the maverick assumed authority: ‘It was a sense of being in control, setting the agenda and making a government bend the knee.’

Several times Rundle poses the question, ‘Who is Clive Palmer?’ The first time precedes his account of Palmer’s early years and the examination of influences that shaped him. The second and third are in the section on the politics of Queensland. The final and most significant occurs at the end of the section called ‘Gaming the System’. This explores the manipulation of the proportional preferential voting system that gave the micro parties their seats, and is prelude to a conclusion advocating radical reform of Australian democracy. That such a call can be based on a brief political career and membership of a Senate only five months old is extraordinary.

The essay contains another refrain. Rundle often reminds us that the case concerning the alleged fraudulent use of the payment to Palmer by his Chinese mining partner is still unresolved. It is yet to be revealed if this political colossus has feet of low-grade iron ore rather than clay.

Comments powered by CComment