- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Lyndon Megarrity reviews 'Kevin Rudd' by Patrick Weller

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The politics of Kevin Rudd

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In modern Australia, politics and public policy appear to reflect a narrow range of managerial, political, and economic opinions. Even the much publicised ‘listening tours’ conducted by politicians seem designed to show that they are sensitive to community concerns, but not so sensitive as to want to change policy direction. What makes current discussion of political issues so dispiriting is that over the last three decades, economic measurements and business ideas have come to dominate public life. Citizens are now treated by the public service and their masters as ‘consumers’, former public goods such as education are now narrowly viewed as a form of economic productivity, and community service providers, such as Australia Post, are written about in the media as mere businesses ripe for privatisation. Between 2007 and 2010, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd gave the impression that he might become the ‘circuit breaker’: a leader whose professed faith in the potential for government intervention and community consultation might lead to a more engaged and empowered citizenry, as well as a government more in tune with the needs of the electorate.

- Book 1 Title: Kevin Rudd

- Book 1 Subtitle: Twice Prime Minister

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 417 pp

Patrick Weller’s Kevin Rudd: Twice Prime Minister is largely about how Rudd tried to manage the high expectations of his 2007 election campaign and get results for the electorate that would justify his government’s existence. The book is structured as a conventional biography, but the author has little to say about Rudd’s first five decades that has not been covered adequately, if a little superficially, in earlier biographical portraits by Robert Macklin and Nicholas Stuart (both 2007). Weller’s real strength is in showing the reader how the machinery of government and policy were coordinated under Rudd. The author explains how the personality and style of prime ministers can affect the way policy is examined and implemented by the government in cooperation with the public service, the Prime Minister’s Office, Cabinet, and other institutional bodies.

What Weller’s work emphasises clearly is the tremendous and probably unrealistic pressure which has been placed on the shoulders of Australian prime ministers in recent times. Partly encouraged by party strategists on both sides of politics, the media has crafted a lazy narrative of prime ministers as being overwhelmingly responsible for the success and failures of their governments. Lacking the time and patience to analyse public policy, journalists focus their attention on the personality and quirks of the prime minister, to the extent that other ministers fade from view. ‘The leader is all’ media philosophy may explain Rudd’s obsessive desire for data, data, and more data on public issues, to the point where decision-making was sometimes postponed indefinitely.

The author’s writing style is genial but bland. Weller’s fundamentally inoffensive tone may be the price he had to pay in order to interview Rudd and his staff on several occasions since 2007, as well as being allowed to observe the Prime Minister’s Office at work at various times. The reader is informed that Weller has ‘known Kevin Rudd for twenty years’, but the nature of that relationship is not revealed.

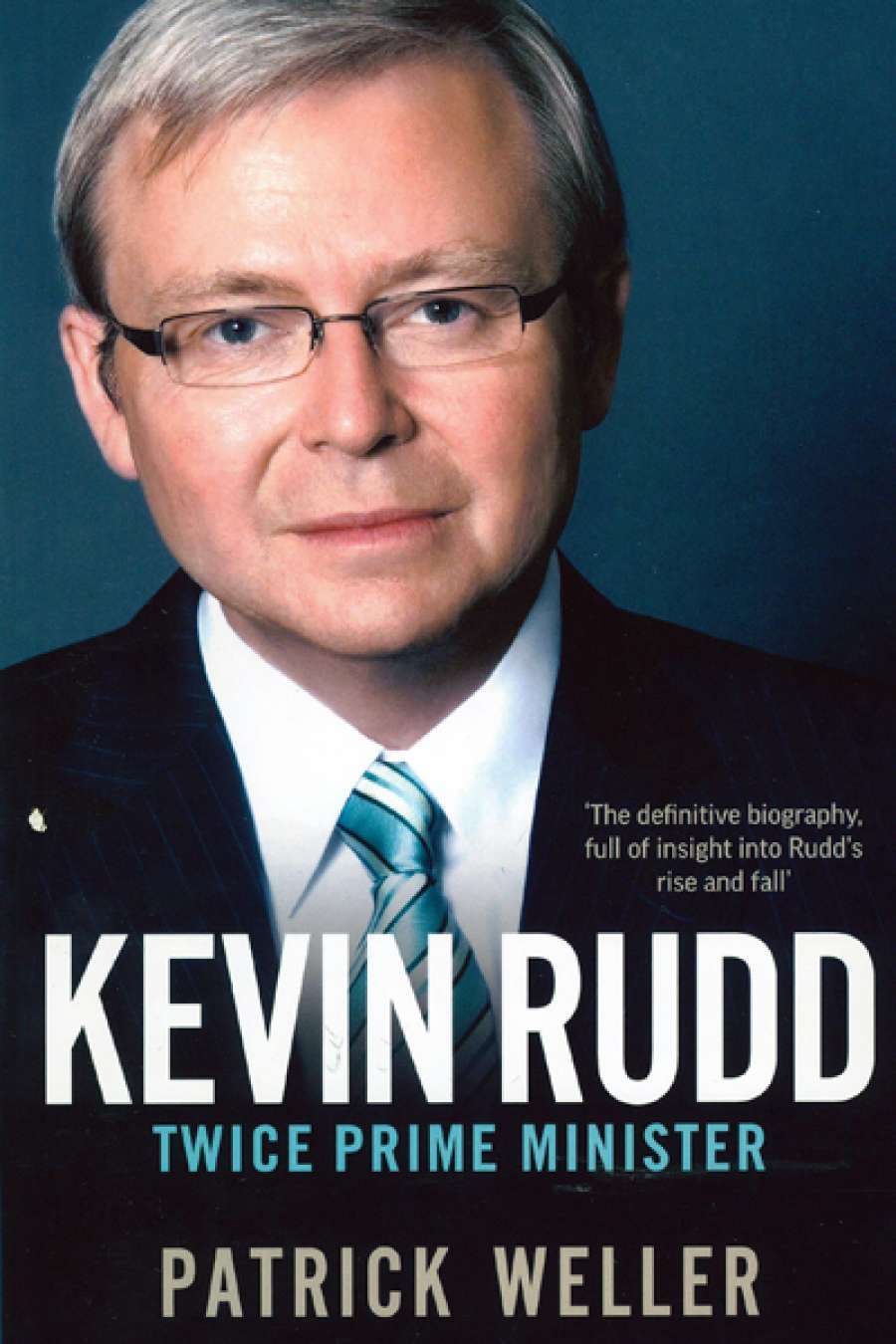

Kevin Rudd (photograph courtesy of Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade)

Kevin Rudd (photograph courtesy of Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade)

Whether it is because Weller is more interested in how political systems work than in biographical narrative, or whether the author has censored himself, Kevin Rudd: Twice Prime Minister is the antithesis of a ‘warts and all’ biography. Warts do get a cursory examination, but Weller has a tendency to state uncomfortable facts without sufficient analysis of what they might mean. Nevertheless, it is clear from this account that Rudd, as an official and later as a politician, lacked organisational and people-management skills. Keeping senior officials waiting for hours and then cancelling the meeting is one example of Rudd’s failure to appreciate the potentially negative consequences of his actions. Given that Rudd’s lack of people skills was allegedly a strong reason why he was removed from office, Weller’s failure to dig deeper when reporting unpalatable allegations against his subject is a major flaw in this biography.

Kevin Rudd’s views on aspects of his career are incorporated within the text, but it is not always clear whether Weller is summarising the contents of a specific interview with Rudd or if he is making assumptions based on a range of sources. The minimalist style of referencing makes it difficult to tell. To his credit, the author has incorporated some of the more recent literature on Australian politics between 2007 and 2013, including Bob Carr’s diary. It is a pity, though, that he does not seem to have referred to the Centre for the Government of Queensland’s Queensland Speaks website. This initiative, which has made available interviews from Queensland politicians and public servants from the 1990s, may have provided useful alternative perspectives on Rudd’s time as a Queensland policy adviser and official.

Weller makes some valid points about the media coverage of the Rudd years. David Marr is given a subtle dressing down for the ‘pop psychology’ in his 2010 Quarterly Essay, in which Rudd was simplistically portrayed as being driven by anger. Whatever the merits of Marr’s writing, it is hard not to have some sympathy for Rudd and other politicians, subject to having their every action scrutinised by a 24/7 media hungry for stories. Weller is also right to highlight the fact that once a government scheme is labelled a disaster, the media and opposition voices can become hooked on the disaster narrative and will not alter their perspective. For instance, the provision of school halls through Rudd’s Building the Education Revolution scheme was reasonably successful in terms of its outcomes, but the media coverage stressed the isolated ‘cock-ups’ rather than the scheme as a whole.

The reader of this volume is left with the impression that personal ambition, rather than anger, drove Kevin onwards, upwards, and downwards. His passion for education, the environment, and other issues seems abstract and secondary to his visceral desire to feel the adrenalin rush of being in the centre of political and government action. The final chapters in the book make grim reading. After having been rejected by his own party in 2010, it appears tragic that he could not think of a better way to spend his time than hanging around parliament and undermining his successor. Rudd’s continued presence as a backbencher and (for some time) foreign affairs minister created perceptions of division within the ALP which were unhelpful to its electoral chances. Rudd’s subsequent victory over his usurper, Julia Gillard, was pyrrhic at best. His return to centre-stage as prime minister in mid-2013 quickly ended in defeat at the September 2013 general election.

The sense of a fresh start that made the first Rudd government highly popular with voters is fading into memory. In general, the electorate has since reverted to cynicism and disengagement from the political process beyond the obligation to vote. It may be that much of our political class prefers it this way.

Comments powered by CComment