- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Mary Eagle reviews 'Strange Country' by Patrick McCaughey

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Painting Australia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

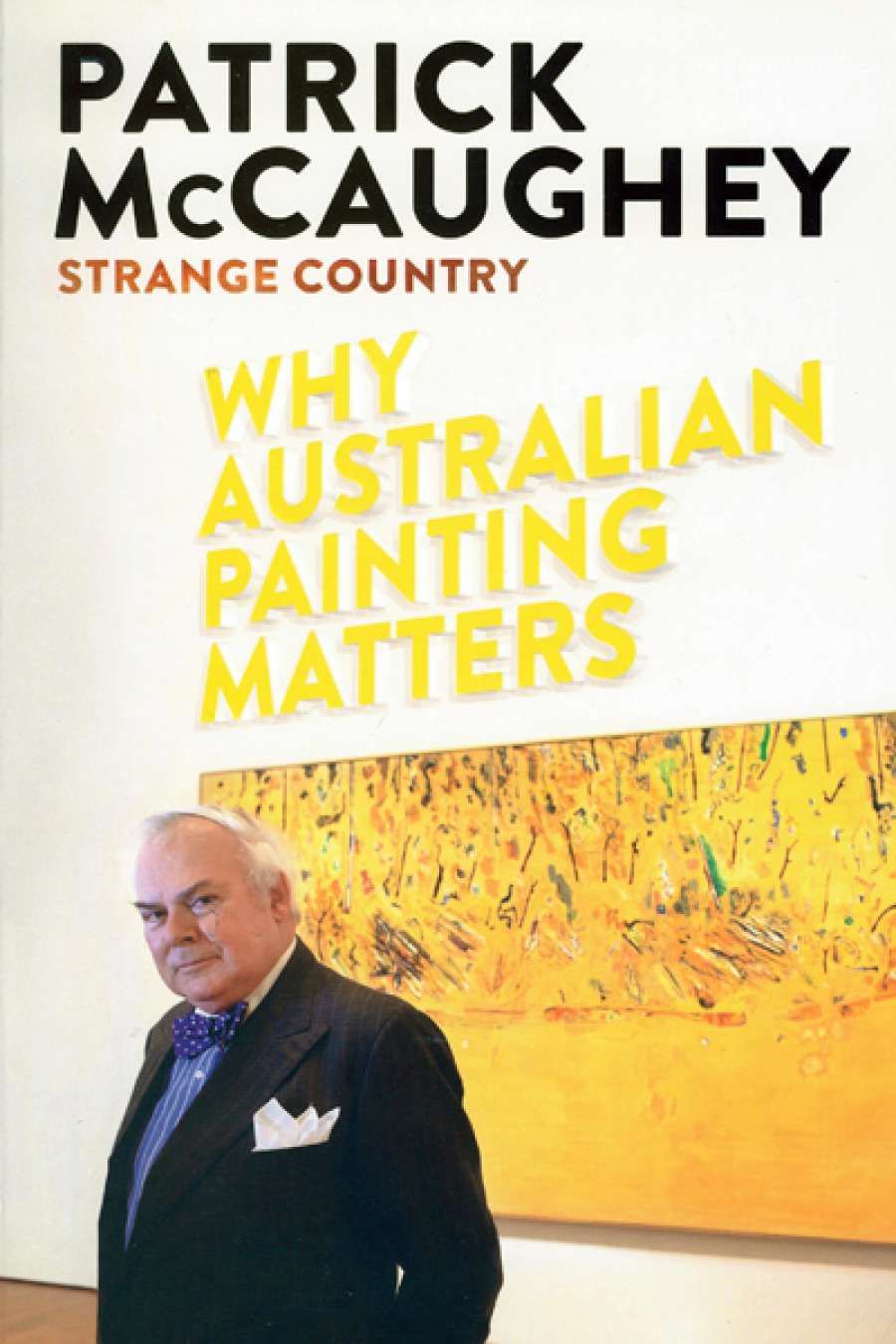

The cover assembles the book’s title and author’s name (writ very large) with a photograph of him, in an art gallery, before a wide yellow landscape by Fred Williams. Turning to the viewer, Patrick McCaughey is about to launch into a story that will satisfy the curiosity teased by the name of the book, Strange Country: Why Australian Painting Matters.

- Book 1 Title: Strange Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: Why Australian painting matters

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $49.99 pb, 376 pp

Next door, an hour later, Patrick McCaughey spoke a concept of history that was ‘Homeric’ in the more usually understood sense of a grand narrative driven by destiny. Belief in the evolution outlined for modern art by the influential American writer Clement Greenberg was to be heard behind his every word. Thomas Kuhn’s formula for the generative role of paradigms in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962)was not a neater thesis. McCaughey spoke then, as he still speaks and writes, with an orator’s flow, portentously (possibly using a tad too many tags), but always pertinently and without wasting a word.

Histories of Australian art have tumbled out one after the other in recent years, all of them using the research of many people, all of them fudging the seemingly insurmountable problem of making a coherent totality out of the mismatched pieces of a story stretching from ancient rock art through a hodgepodge of colonial striving into a meek British twentieth century cooled at the edges by splashes of war and immigration, and closing with an assumption-shattering renaissance in Aboriginal art. This book’s affirmation of art lifts it to top position.

McCaughey proffers ‘strange country’ – not innovative art – as the reason ‘why Australian painting matters’. Impossible, therefore, not to see the publication in the light of the exhibition Australia at London’s Royal Academy in 2013. Many British critics panned the exhibition: even to my loyal eyes the display was a mess and the landscape concept fatally compromised. Yet the British public attended in droves, in part because Edmund Capon performed a great service, hosting a four-part BBC series The Art of Australia, which was aired in the United Kingdom at the time of the exhibition. McCaughey now offers an equivalent gift in the form of an intelligent, readable history. A skilful writer with a knack for brisk synthesis, he has shaped a text that perfectly represents the latest scholarly opinion while also resolutely voicing his own loyalties.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Big Yam Dreaming, 1995

Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Big Yam Dreaming, 1995

The choice and weighting of the reproductions tells all we need to know about the way by which the author’s personal knowledge has informed the tale: sixty-four works of art from the nineteenth century compared with 203 from the twentieth century; eighteen works of Aboriginal art after 1970 compared with thirty-eight of Euro-Australian art of the same period. The relative number of reproductions given to artists reflects both personal preference and the landscape and painting themes of the book. At the top there are nineteen reproductions of works by Fred Williams, sixteen by Sidney Nolan, twelve by Russell Drysdale, eleven by Arthur Streeton, eleven by Arthur Boyd, nine by Tom Roberts, nine by Frederick McCubbin. Major colonial and Aboriginal artists get four each. The text is threaded with the key works and words that will hold together the narrative theme of exploration and discovery: of country, inner world, spirituality, Nietzschean vitalism, and the medium of painting.

The argument is that ‘strange country’ has pulled venturesome art in Australia and thereby made painting and place grow together indivisibly. ‘One of the most striking aspects of Emily Kngwarreye’s career was her capacity to change her style without ever relinquishing her beliefs. She made discoveries about her Dreaming and her Country in the act of painting. Her art enabled her to see and say more as the scale of her art grew.’ Colonist John Glover conveyed ‘a sense of strangeness, the “otherness” of his newfound land’. Materialistic expectations of pastoral riches to be discovered ‘led to geographic names such as Mount Hopeless’, whereas aesthetic exploration led to the outflung arm of the explorer–scientist in the foreground of Eugene von Guérard’s Mt Kosciusko that ‘sums up the visionary moment, the amazement at the scene before him, the “wild surmise” of the explorer’. From the 1850s on, the more distinguished of Australian painters ‘internalised observation into feelings about the landscape’.

Eugene von Guérard: North-East view From the Northern Top of Mount Kosciukso, 1863 (photograph courtesy of NGA)

Eugene von Guérard: North-East view From the Northern Top of Mount Kosciukso, 1863 (photograph courtesy of NGA)

Strange country has been encountered in urban, private, sexual, and spiritual realms. Perceptions of it differ. Thus McCubbin’s sense of Collins Street, Melbourne ‘as a continuous living organism, each element acting on another like a molecular charge’ was echoed mordantly fifty years later in the sour yellow faces of John Brack’s Collins Street, 5 pm. A child of the Edwardian era, Grace Cossington Smith explored light and spirituality until, in the 1960s, she was capable of informing a square stroke with divinity. Around the same time, young Peter Booth’s black paintings were opening upon ‘the void’. In European and Aboriginal art, humans and their attributes morphed into landscape, whether Old man’s Dreaming on Death or Destiny in a painting by Mick Wallangkarri Tjakamarra, or naked bathers in Afterglow (Summer Evening) by McCubbin, poor white ‘hunter-gatherers’ in a landscape by Drysdale, or the stiff chrysalis of a Bride by Boyd. At the apogee of this history, where modern art and strange country meet, is Fred Williams (a towering figure in McCaughey’s estimation) who tips the balance from engaging with the landscape as ‘a scene’ to addressing its ‘obdurate quality’ as a ‘challenge to pictorial form’.

If McCaughey is now proposing ‘strange country’ for ‘why Australian painting matters’, he believes it is the ground on which the pieces fit together, and will make a good fist of convincing us. He made his impress in the 1960s and early 1970s as one who stood for aesthetic quality as a universal standard and for Western art’s predestined path of exploration. As a critic, he measured Euro-Australian art by its timeliness in mainstream developments but was prepared to acknowledge in print that an assessment by that standard might not agree in every instance with an aesthetic ranking. Strange Country held two interests for this reader. How were the values of locality and aesthetics combined – do they combine? And contemporary Aboriginal and Western art – do they flow?

By putting contemporary Aboriginal art at the beginning of the book rather than in its chronological place, towards the end, McCaughey misses a historical turn in the progress of art, when Western painting momentarily lost itself in the expanding horizon of an art beyond its keeping. The book limps to an end partly as a consequence, and partly because, although painting has flourished in recent decades, sculpture, photography, assemblage, installation, etc. have especially thrived.

Comments powered by CComment