- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Martin Thomas reviews 'Battarbee and Namatjira' by Martin Edmond

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A new lens to understand Namatjira

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There was something of the alchemist in Albert Namatjira. Using the most liquescent of media, he created impressions of the driest terrain. Painting in watercolour involves the fluid dispersal of pigment. Yet in Namatjira we find colours distilled in such a way that each landscape glows with a quiet intensity. This evocation of light reveals the influence of Rex Battarbee, who, long before he began to tutor his famous protégé, voiced dissatisfaction with ‘traditional methods’. He developed a painting technique of his own, specifically designed to ‘achieve luminosity’. Like many an inventor, he was cautious about sharing his discovery, in part because he believed that artists should develop on their own terms. But Namatjira was so keen an observer of his then master that he would have realised if Battarbee had withheld information. So Rex decided to teach him everything he knew, both for the sake of Namatjira, whom he clearly adored, and more generally and altruistically ‘for the sake of the Aborigines’.

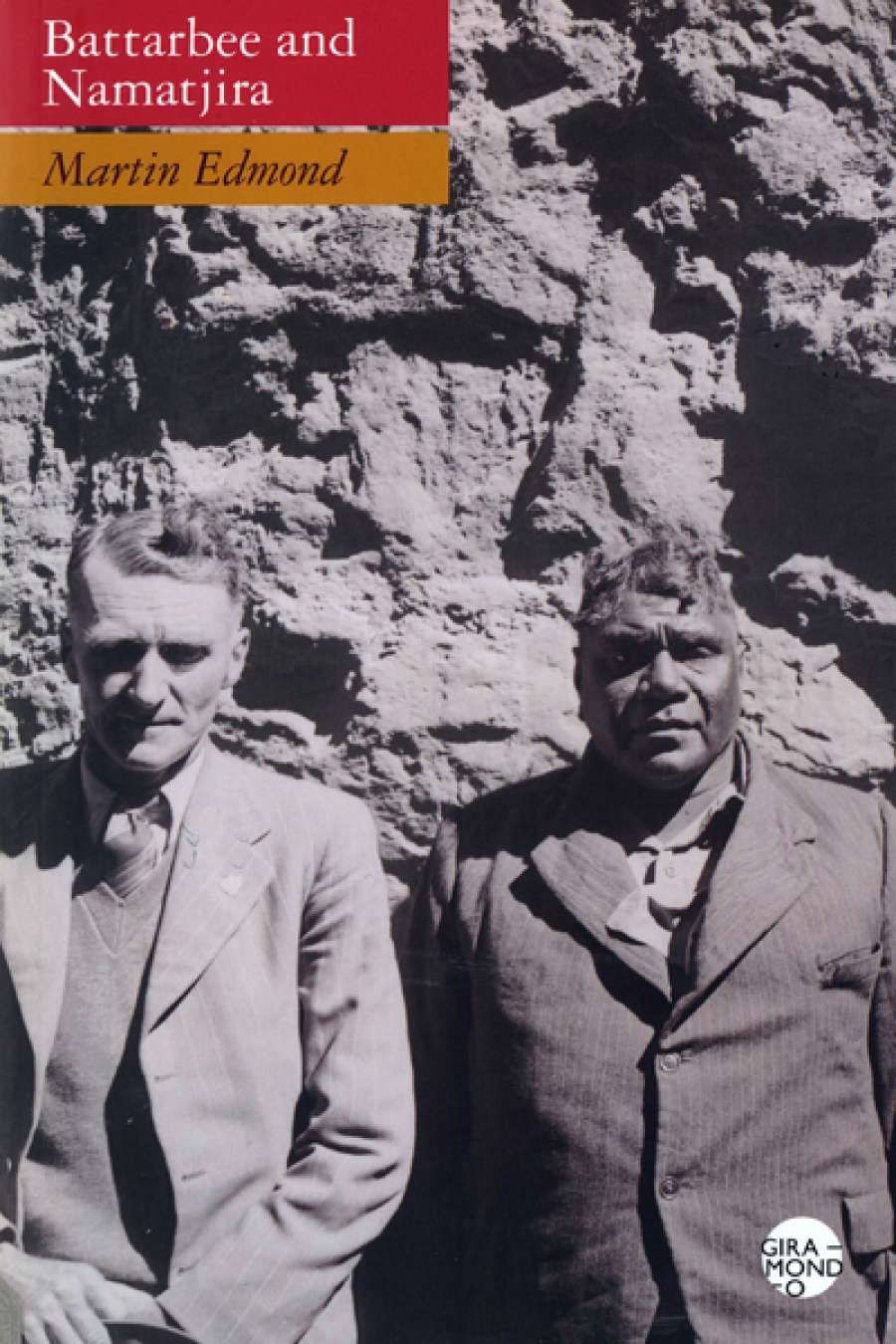

- Book 1 Title: Battarbee and Namatjira

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo Publishing, $29.95 pb, 341 pp

The Albert Namatjira story has been told many times since the gentle Central Australian shot to artistic stardom in the 1930s. The beginnings lie in the ancestral country of the Arrernte people, the terrain depicted in the paintings. There is the unique influence of the Lutheran polyglots at Hermannsburg mission, where Namatjira was raised. Success in painting plucked him from obscure occupations that included camel driving and making poker-work artefacts – an earlier artistic endeavour in which he also excelled. Once Namatjira learned to paint he did so with unbridled energy. He exhibited widely, became the first Aboriginal Australian to claim an entry in Who’s Who, and grew into something of a cultural ambassador. He sold everything he painted, often before it could be exhibited, and he made a healthy income. Then came the downfall: disappointments familial and political; a growing taste for liquor; weight gain and a decline in health; pressure, irresistible in his culture, to share his gains with kith and kin; arrest and conviction for supplying alcohol to a kinsman; death from heart failure at the age of fifty-seven. The story is familiar, and while Aboriginal Territorians are no longer wards of the state – as Namatjira was for much of his life – it is shocking to realise how little has changed.

Albert Namatjira outside Government House in Sydney, c.1947–50 (National Library of Australia)

Albert Namatjira outside Government House in Sydney, c.1947–50 (National Library of Australia)

Martin Edmond’s book plots this chronology, as do all the others. Where it differs from its predecessors is in its treatment of Battarbee, who until now has played only a cameo role in the Namatjira story. Admittedly, neither Charles Mountford, who published the first book on Namatjira in 1944, nor any commentator since, has failed to acknowledge the catalytic influence of Battarbee, a watercolourist and former commercial artist from Victoria. Yet for the most part, the mentor has remained in the shadow of the legendary figure whose dramatic rise he enabled.

In rescuing Battarbee from two-dimensionality, Edmond contributes a significant corrective to the art history of Australia. Battarbee’s plein-air lessons in painting were clearly seminal, but Battarbee’s influence went much further. He acted as Namatjira’s agent and promoter. He attended to practicalities, ensuring that the supply of art materials was maintained. He exhibited paintings and chaired the Aranda Arts Council, an organisation designed to market the work of Namatjira and the other Aboriginal watercolourists in his circle. With its modest commissions and tireless campaigning for the economic and intellectual property rights of the artists, it was a progenitor of the Aboriginal artists’ centres that later mushroomed throughout the Centre and Top End. Battarbee was an ethical and compassionate man whose own output as a painter was inevitably compromised by his role as an advocate and administrator.

Martin Edmond is a distinguished New Zealand writer who began to explore this topic when a friend shared a cupboard full of material on the two painters, gathered for a documentary film that would have been titled Albert and Rex had it ever been made. The deeply moving book that is the belated legacy of that research is a reminder of how life writing as a project has been recalibrated in recent years. Like Richard Holmes’s Dr Johnson and Mr Savage (1996) (read it if you don’t know it), Battarbee and Namatjira is a parallel biography. The two subjects were entwined by a common passion for the desert country which they knew so differently, yet rendered in forms that were roughly similar, on the face of it at least. This is a story of art and artistic influence: the migration of thought, image, and expression between individuals and across cultures. A big-picture drama is played out in the intimate context of a friendship, albeit one that became increasingly strained as the years passed.

Battarbee’s life story is scarcely less fascinating than Namatjira’s. A farming boy from rural Victoria, he might have followed in his father’s footsteps and led a life on the land. World War I intervened. In France he was so badly injured by machine-gun fire that he was left for dead in No Man’s Land. Rescue came eventually and he was repatriated to Melbourne. The war injuries plagued him for the remainder of his days; his left hand was reduced to a lifeless claw. He was in hospital for years. Reluctant to become a lift attendant or the likes, he enrolled in an art course, inspired by a sister who also painted. Fortunately, he was right-handed.

Albert Namatjira with Axel Poignant and Rex Battarbee, 1946 (photograph courtesy of Arthur Beau Palmer)

Albert Namatjira with Axel Poignant and Rex Battarbee, 1946 (photograph courtesy of Arthur Beau Palmer)

Battarbee found regular work in advertising. Yet he craved adventure, his disabilities notwithstanding. Salaried certainty was abandoned for a life of outback adventure. Travelling with a fellow artist, John Gardner, in a truck cum studio cum home, he first visited Hermannsburg in 1932. What he found there is now difficult to imagine. Thanks to Namatjira, the vivid hues of the MacDonnell Ranges have been etched into the visual vocabulary of the nation. Yet when Battarbee first went there, the country was fairly unexplored in terms of Western art. The Hermannsburg mob looked on as the painters painted, intrigued at the spectacle of familiar country depicted from so unorthodox a perspective. The sheer alterity of depicting this topography with a horizon and ‘conventional’ perspective cannot be overemphasised. It is so different from the art making indigenous to the region, with its codified symbolism of tracks, waterholes, and land forms, seen from above, that a more recent generation of desert painters has contributed to the visual conversation.

Albert Namatjira, 1949

Albert Namatjira, 1949

Melburnians were no less fascinated by Battarbee’s portrayal of the Centre. He exhibited, sold work, won awards, and for a time enjoyed fame as an artist in his own right. Cashed up from sales, his pilgrimages to the Centre became more frequent, and that is how he came to know Namatjira, whose hunger for art lessons was in no way diminished when he learned that a single painting could fetch fifteen guineas. Battarbee watched incredulously as his precocious student began to flower.

Edmond suggests that in order to understand his conjunction with Namatjira, we must recognise Battarbee’s own achievements as an artist. In sensuous prose, he argues that it is certainly time another look was taken at what Battarbee accomplished: ‘the distant purple ranges knotted like muscles along the skyline or standing as ramparts against the blue; the sand hills and gorges, the rocky faces like slabs of meat; his trees with their tracery of light and dark along the trunks; his tribal portraits and portraits of his fellow artists, some of which are awkward and strange and others replete with insights nobody else has had.’

Helen Burns, the daughter of Pastor Friedrich Albrecht of Hermannsburg remarked that ‘with Rex’s painting, it’s almost as if you are looking at a delicate curtain’. Lloyd Rees discerned in Namatjira ‘a marvellous sense of distance and of space. His eyes can look so far away and seem to know what’s there.’ Coming from a late master of the landscape tradition, this is effusive praise indeed.

Edmond is as close a reader of Namatjira’s art as he is of Battarbee’s. The descriptions of those familiar hills and ghost gums, the almost microscopic rendering of detail that is a hallmark of Namatjira’s oeuvre, make for some of the most enjoyable passages in the book. Thinking through my response to the text, and the re-engagement with the paintings it encourages, I suspect that I am not alone in regarding Namatjira’s paintings as deeply enigmatic. For all the homely familiarity, there is something uncanny in the facility with which this indigenous man adopted the visual codes of the coloniser and used them to re-present a homeland that was – and was not – his own. In comparison, the Papunya Tula painters, several of whom practised as watercolourists à la Namatjira before they turned to acrylic and canvas, offer simpler verities, rooted as they are in the certitudes of connection to country and tradition.

Namatjira, in contrast, is like hearing some old bush ballad, sung in perfect pitch – and in a foreign accent. Perhaps it was this that the modernists couldn’t stand. John Reed of Heide fame denounced his work as ‘clever aping’. Bernard Smith recorded that Hal Missingham and others at the Art Gallery of New South Wales complained that if Sidney Nolan ‘could paint primitive paintings then surely a real primitive man ought to be able to do so’. While the cognoscenti tut-tutted, the public paid what it could to get a piece of the action: originals for the lucky few; reproductions for the common herd. I have vivid memories of the latter, suspended from the picture rail in the house of an honorary aunt. Martin Edmond provides a new lens for apprehending these mysteries. In their white frames and mounts, they always looked like desert mirages that a viewfinder had preserved. Arguably, that is exactly what they are.

Comments powered by CComment