- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'Jovial Harbinger of Doom: short stories of Laurie Clancy'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A story called ‘The Burden’, which appears at about the halfway mark of this collection, begins like this: ‘Graham was finding the burden of freedom a little too much for him …’ He is working alone in his room above a Chinese restaurant near the Berkeley campus of the University of California, where he is a visiting Australian Fellow, writing a novel about, it seems, academic life. But the novel isn’t ‘coming along’. He is ‘stuck hopelessly in the middle of a quarrelsome English department meeting from which he couldn’t extricate any of his characters’. He has run out of money and food and is down to his last half gallon of Red Mountain claret. ‘Nothing for it but to do the tourist thing and wander down Telegraph avenue with a camera.’ And so begins his afternoon of boredom, inchoate intentions that evaporate as they arise, and chance meetings. Looking back on it at the end of the day, he decides there was ‘not much to show for it … Or maybe there was something there. He pulled his notebook towards him and began to write, “Graham was finding the burden of freedom a little too much for him …”’

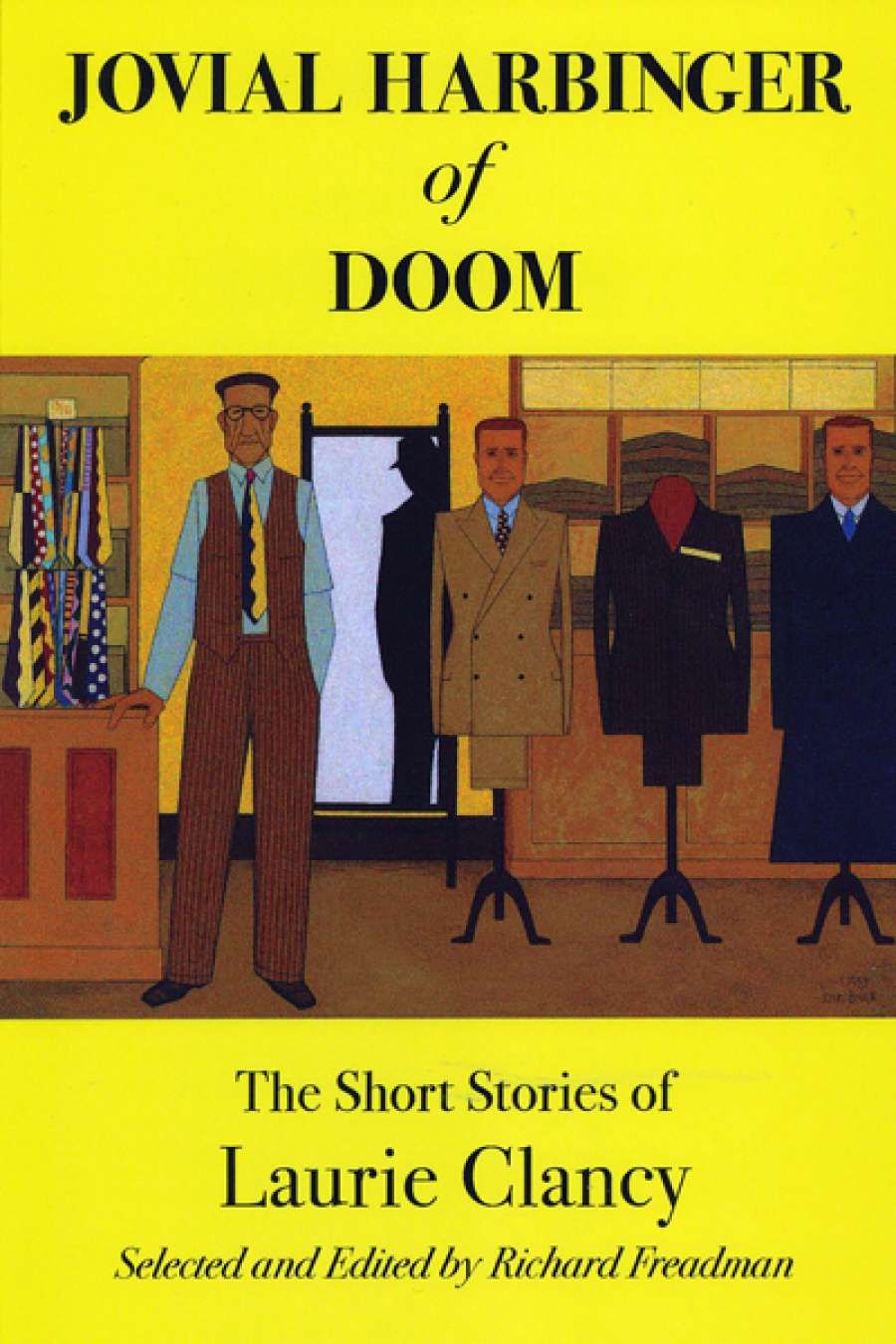

- Book 1 Title: Jovial Harbinger of Doom

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Short Stories of Laurie Clancy

- Book 1 Biblio: Michael Hanrahan Publishing, $35 pb, 407 pp

In one sense the story goes nowhere – it ends literally as it began. But the repeated sentence carries a weight and an excitement that contrast with the weariness, the implied ennui, of its opening counterpart because Graham – and shadowy behind him, Clancy – has recognised the understated narrative momentum of the ordinary, of quotidianism. If you have read the stories through in the order they appear, you realise on coming to ‘The Burden’ that it is simply adopting, more explicitly than usual, a mode Clancy has already marvellously exploited from the beginning. It is not, needless to say, that he routinely ends as he began; but many stories seem on the surface not to have advanced very far or at all until you sense the charge carried unobtrusively by the final narrative moves.

Laurie Clancy (photograph courtesy of Richard Freadman)

Laurie Clancy (photograph courtesy of Richard Freadman)

In ‘Master of Deception’, for example, the serially truant schoolboy, Fitzroy Herbert, devotes his energy and time to weaving and maintaining a ‘protective cocoon’ of concealments and false evidence so that his mother has no inkling of his double life. He has some close calls, and he needs to keep ahead of the game, the conclusion of which, presumably, lies far beyond the last words of this glimpse into his dedicated tuning of ‘the monstrous tissue of lies he has strung together’. The story ends with Fitzroy pondering his next move to fend off enquiries from the school while watching television and arraying his school books for instant, phoney attention if his mother arrives. ‘The phone rings but he decides not to answer it …’

‘The Vigil’ traces the travails of a lovesick boy obsessed with the beautiful young woman who has recently moved in next door. Before he begins actually spying on her, he listens to his parents discussing them.

‘They’re migrants, refugees,’ Leo’s mother said. ‘From one of those Balt countries.’

‘The girl’s already enrolled part-time at the university. In law,’ his father said, not to be outdone.

Leo wondered how they came to know these things. His mother did talk to the local tradesmen … but his father hardly ever left the house …

‘The three of them go to church on Sundays, regular as clockwork, the Catholic one, St Joseph’s,’ said Leo’s mother, upping the stakes.

This exchange is important to our understanding of what happens to Leo’s infatuation, but it is also a fine example of Clancy’s unobtrusive wit, as the conversation becomes a kind of verbal card game between the competing parents. At the dénouement of his passionate drama, Leo is left stunned and irresolute: the story’s last words are, ‘He stared at her.’ It is the same surrender to the weight of circumstance as Fitzroy Herbert letting the phone go on pointlessly ringing until the answering machine takes over. There are many comparable stories – among others: ‘Hitch-hiking’, ‘First Love’, ‘The Trevalen Party’, ‘The Academic Dinner Party’. These and others like them are tremendously accomplished, shaped from delicate filigrees and suggestions of experience too ungraspable to sustain conclusiveness or closure, ending as often as not with a variation on the freeze-frame. It is the mode in which I think Clancy excels.

The stories of sexual treachery, as Richard Freadman calls them in his penetrating and elegant critical introduction, are often denser and more extended. At their very best – as in ‘In Barcelona’, a Thurberesque battle of the sexes that deepens and darkens towards a shock climax; or ‘Spinning Jenny’, grim, tragic inevitability honed by an anguished narrator’s helplessness – they are triumphs of jaundiced or rueful or thoroughly self-cauterising guilt, regret, or the failure of love. Or, as things turn out, love’s absence. While there is a lot of sex in Clancy’s fictional world, there is not much love, just as there is not much nature. He is fascinated by how people make and unmake their lives in the shoulder-to-shoulder milling around of a city: to this fascination he adds a mordant, brilliant wit and an overarching sense of amiable gloom.

Perhaps he is most comfortable in the memoir-like pieces (‘How I Nearly Got to Meet Norman Mailer’) or the justly famous ‘The Annual Literary Test Match’. But Clancy – a writer of great intelligence and massive range of reference – could handle any mode or form to which he gave his full attention, and Jovial Harbinger of Doom is testament to his extraordinary gifts.

It was a stroke of genius to conclude with Laurie Clancy’s ‘Auto-eulogy’ written shortly before his death and read at the funeral by his son, Joe. It is funny, immensely moving, and – perhaps at last and without qualification – full of love.

Comments powered by CComment