- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

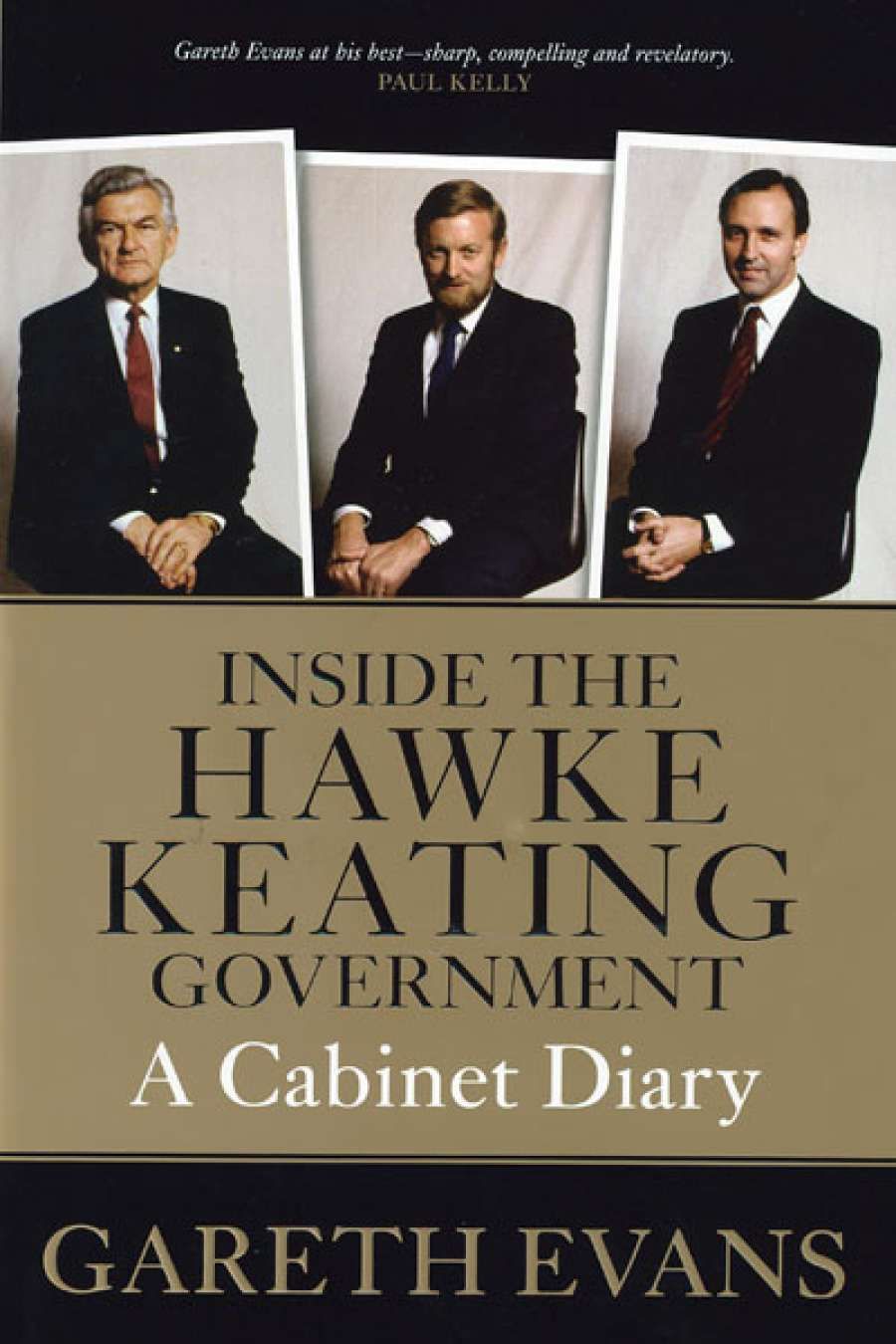

- Custom Article Title: David Day reviews 'Inside the Hawke–Keating Government' by Gareth Evans

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Diary of a confidant to Hawke and Keating

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gough Whitlam was fond of replying to requests for interviews from historians by saying that all the answers could be found in the archives. ‘Go to the documents, comrade’, was his refrain. However, official documents rarely tell the whole story, particularly those from the modern era, whose authors are conscious that their words could so easily be exposed to public scrutiny. In particular, they are usually bereft of the innermost thoughts and motivations of the politicians and public servants. By contrast, politicians’ diaries can be goldmines. Written contemporaneously, an unguarded diary entry can transform our understanding of people and events.

- Book 1 Title: Inside the Hawke–Keating Government

- Book 1 Subtitle: A cabinet diary

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $49.99 hb, 432 pp

Unlike their British or American counterparts, few Australian politicians have maintained private records of their doings. Until recently, the Hawke–Keating governments (1983–96) had produced just one published diary, that of health minister and former political scientist Neal Blewett: A Cabinet Diary: A Personal Record of the First Keating Government (1999). That diary only covers part of the first Keating government, from January 1992 to March 1993. Blewett found that the pressure of ministerial work left him with little time to maintain a diary throughout the Hawke government. It was only when Blewett decided that he would retire at the end of the first Keating government that he began a personal record of his final fourteen months in politics. As a result, the diary is written by a relatively dispassionate observer who knows his days in politics are coming to an end, and who wrongly thinks the Keating government is doomed. It is a pity that Blewett didn’t stay around. He would have been able to record Keating’s second term, when he confronted the great challenges of Mabo, the republic, and Australian relations with Asia.

While the Blewett diary is devoid of the heat and passion of a Cabinet minister trying to fight his way to the top, the same cannot be said of the latest contribution to this tiny literature. Gareth Evans was a politician who believed himself capable of becoming prime minister. With a sharp mind and a background as a legal academic, he was one of Bob Hawke’s praetorian guard when Labor leader Bill Hayden was forced to resign in 1983. When Hawke won the 1983 election, Evans, who had been elected to the Senate in 1978, confidently expected to be rewarded with high office. Apart from Hawke’s job, the one that Evans most coveted was that of attorney-general, a position which he filled with some distinction during Hawke’s first term in office (1983–84) before being shifted to the minerals and energy portfolio. Evans had fallen in Hawke’s estimation after authorising RAAF flights to spy on the dam-building activities of the Tasmanian government. Dubbed ‘Biggles’ by the press, he was invariably portrayed wearing an aviator’s goggles by cartoonists. He had also pushed too hard to create an Australian bill of rights in the face of opposition from Hawke and some of his colleagues.

Evans’s subsequent failure to gain pre-selection for a lower house seat ended any ambition he harboured of succeeding Hawke as prime minister. It was in this context that he began keeping a diary. He intended to provide an account that would be as full and frank as possible. Like Blewett, his exemplar was the British politician and diarist Richard Crossman; he even went on a pilgrimage to Crossman’s farm in Oxfordshire, where he looked admiringly ‘from the boundary fence, at a place which must be something of a shrine’.

Again, like Blewett, Evans found that the task of emulating Crossman was beyond him. Whereas Crossman published a three-volume diary of his six years in the Labour Cabinet, Evans only managed to keep a diary for two of the thirteen years he spent in the Hawke–Keating ministries. The daily task of recording his thoughts proved too overwhelming.

Despite this, the diary covers a crucial period in the Hawke government, from September 1984 to October 1986. It was a time when Hawke and Keating were pressing ahead with their economic reform agenda. This was based on notions of economic rationalism, which caused Evans to be ‘alarmed – like a great many others in the [Labor] movement – about the prospects of the Party losing its soul’. It was also a time when Keating was thwarted in his desire to introduce a consumption tax and became vociferous in his criticisms of Hawke, and intent on staking out his own claim to the leadership.

Bob Hawke, 2012 (photograph by Eva Rinaldi)

Bob Hawke, 2012 (photograph by Eva Rinaldi)

Evans was a confidant to both men, and his diary provides a unique record of the deterioration in their relationship. It corroborates Keating’s suggestion that Hawke lost focus for a year or more after discovering in late 1984 that his younger daughter was a heroin addict. The diary has Keating complaining in July 1985 of the dangerous ‘state of drift’ into which Hawke had slumped and which ‘would bring the Government down’. In Keating’s view, Hawke was a ‘lucky mug who doesn’t know what he wants to do with the country, what he wants to do with his life, or where he wants to lead the Government’.

In November 1985, Evans witnessed a heated argument between Hawke and Keating, during which ‘they were both pale and tense and almost shaking with anger’. This was ‘a marriage of convenience and no more’, he observes. Seven months later, during a late-night chat with Keating, both of them agreed ‘that after each having been screwed dozens of times by Hawke, there wasn’t much left of the first fine careless rapture, but we didn’t have to be in love with him for the marriage to keep jogging along’. Which it does for another five and a half years, arguably making the eight-year Hawke government and the five-year Keating government the most successful and productive ones since World War II.

Apart from charting the growing estrangement between Hawke and Keating, Evans’s diary covers the beginning of his campaign to become foreign minister and the dogged political pursuit by the Liberals of the radical High Court Justice and former Attorney-General Lionel Murphy, who had been a passionate advocate of human rights and an inspiration for Evans. After Murphy’s reputation and position were tarnished by allegations of impropriety due to his association with a dodgy solicitor, the diary concludes with the judge’s death from cancer in October 1986. It was ‘a great Australian tragedy’, said Evans, who reminded journalists of Murphy’s ‘intellectual energy, his genuine passion for ideas, and his commitment in particular to the ideals of justice, equality and human rights’. Evans could have been speaking about himself.

We may have only two years of Evans’s remarkably frank diary entries, but they will be read with interest by present-day political junkies and picked over by grateful historians for many decades to come.

Comments powered by CComment