- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Michael Shmith reviews 'Rules of Engagement' by Kim Williams

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The ‘lifescape’ of Kim Williams

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What this is not, as Kim Williams is quick to tell us (introduction, paragraph two), is a dog-bites-Murdoch account of that nasty business in August 2013 that saw Williams summarily ousted as chief executive of News Corp Australia. Other disgruntled former Ruprechtian courtiers such as former editor-in-chief of The Herald Sun Bruce Guthrie, who sought and won legal redress and indeed wrote an account of his experiences (actually called Man Bites Murdoch), have told their stories, and told them well. But this is not the path of the enigmatic and enlightened Kim. Instead, as he says, this is a book about ‘one of the most precious things in life that drives most of us … our passions’.

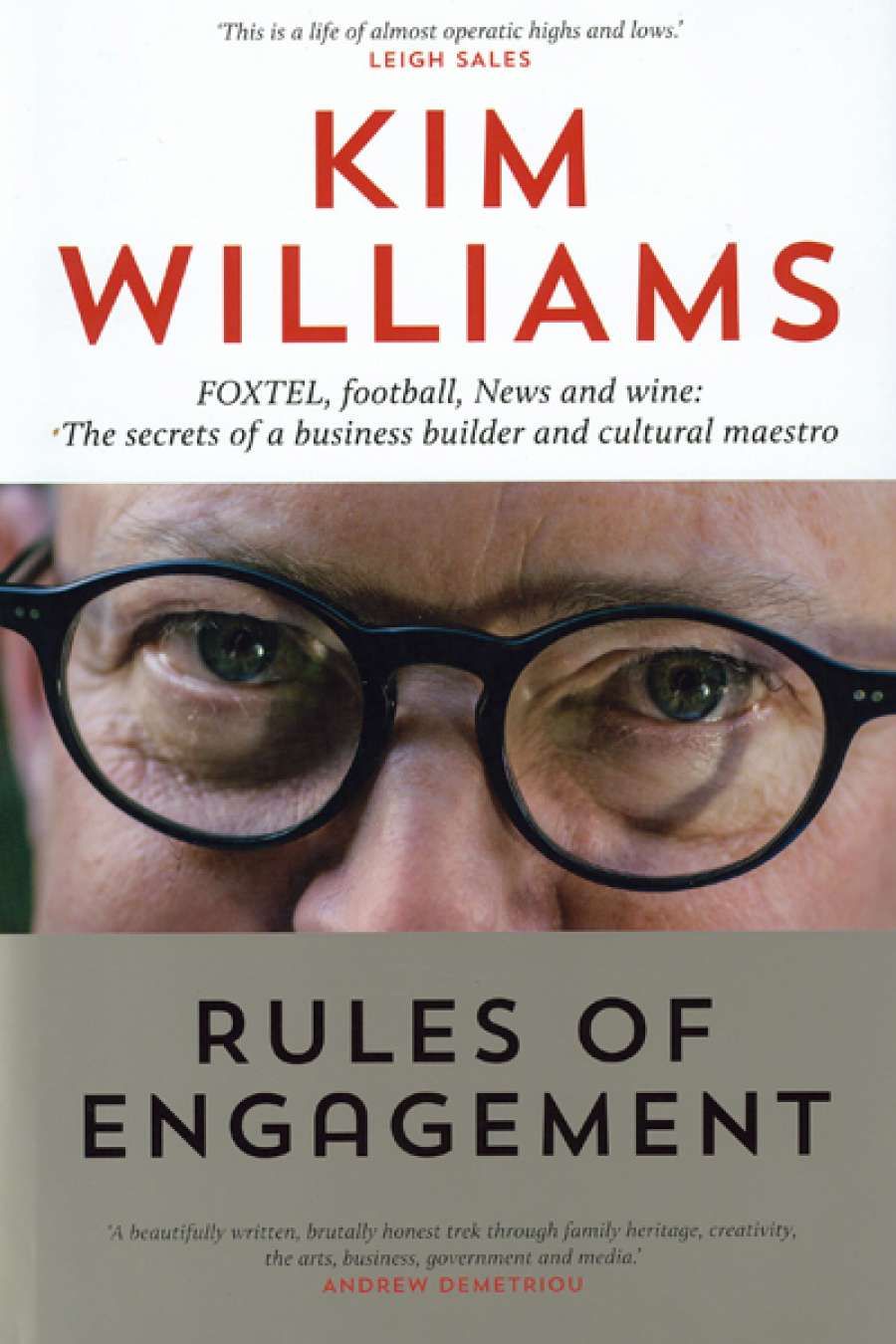

- Book 1 Title: Rules of Engagement

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $44.99 hb, 325 pp

Williams’s life has been just that: passion; but passion tempered with a hard-headed business sense that took him to the top of Australia’s media tree. Like many others, I hope the story he says ‘is best left for another day’, will materialise sooner rather than later. But don’t bet on it. Williams says he has written in detail about his News Corp experiences, but this won’t be released for ‘many years hence’. Meanwhile, we must judge his own story as he tells it: limitations apply. As they said about the Titanic, that wretched iceberg only got in the way of what was up until then a cracking good yarn.

Williams prefers to call his memoir a ‘lifescape’, as indeed this one turns out to be. The subtitle defines Williams’s ‘lifescape’ as ‘Foxtel, football, News, and wine: The secrets of a business builder and cultural maestro’. This cumbersome description, a cross between a self-help manual and speaker-agency blurb, does not exactly clarify the point or purpose of this book. Indeed, its author has gone out of his way to make his book an anti-memoir: ‘… not a chronological narrative … It is the story so far told through a series of reflections on experiences and ideas that have shaped and influenced the course of my life.’

The result is what used to be known as a commonplace book – a piecemeal assemblage of the incidental and curious, presented in no particular order except to reflect the character of its compiler. In art terms, this fragmentary ‘lifescape’ is more of a collage than realistic. For good measure, Williams refused to have an index, advising us to ‘read the book’ instead.

Kim Williams

Kim Williams

Yet, persevere, and there are rewards. What has always fascinated me about Kim Williams is his equal facility and success in two very different fields of endeavour: the Dionysian and Apollonian sides of his nature. In his case, the first is his cultural side, especially music and film, and the second his more hard-headed business side. Not every chief executive can claim to have been music assistant to Italian composer Luciano Berio and his wife, the great mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian (let alone having an affair with Berberian, who was the same age as Williams’s father). But then, not every musician grows up to work with (and be sacked by) Rupert Murdoch or to be told by Kerry Packer, ‘You’re stealing my fucking money.’

As good old Nietzsche had it, the seemingly contradictory Apollonian and Dionysian forces are mutually dependent. Without Apollo, there can be no form or structure; without Dionysus, no energy and passion. And there is that ‘passion’ thing again.

So as we duck and weave through Williams’s life, ’twixt music manuscript-paper and annual reports, concert halls and think-tanks, board rooms and screening rooms, themes and variations occur and reoccur in all sorts of ways. These are complemented by various lists, large and small, of what one could term Kim’s favourites – films, television series, books, wines, and quotations. ‘Five favourite and pertinent aphorisms’, including George Bernard Shaw and H.L. Mencken, concludes with ‘If you don’t know what and why you are doing something then you will inevitably get lost and run out of provisions’: Kim Williams.

His narrative begins in startling, endearing fashion, with a chapter devoted to his mother, Joan, whom he calls the most important influence on his life. Despite dying in 2008, the late Mrs Williams remained an active presence to her son: ‘… bold and confident in life and, as I now discovered, in death.’ Indeed, just two weeks after crossing over, Joan manifested herself, silent and stern, to her son during a speech to the NSW Public Education Foundation. When a book begins like this, how could one not keep going?

Mind you, there are some stumbling blocks along the way. Curiously (for me, although business journalists might think differently), the strictly corporate chapters on media and marketing etc. veer towards the bullet-point didactic; the chapter on wine is suited more to a specialist journal. Yet, in the chapter ‘Political Encounters’, Williams rightfully gets stuck into ‘the parade of unusually ignorant and ill-informed persons standing for public office’, arguing ‘the system cries out for change’. (Kim, have you ever thought of standing for parliament?)

Williams is at his most incisive when he writes about human qualities rather than broader subjects. For example, his chapter on the meaning of friendship and trust takes a swipe at the cult of celebrity, and how ‘the ephemeral all too often rules the day in our media’. He is just as enlightening on the subject of listening, which he calls ‘our least developed skill and yet the world is dependent on it’. Here, in Williams’s view, business and music are as one:

When listening to a piece of music you move into another space in a way that requires you to surrender yourself to the composer and the performers in order to follow that which is happening and take from the experience all that it offers. Over time it becomes second nature and with practice it translates into other dimensions of life – especially thinking and conversation.

What Rules of Engagement needed overall was better, tighter editing. Various spelling errors worm their way in. For example: Nikolaus Harnoncourt is spelt thus, not ‘Nicholas’; Musica Viva’s legendary general manager, the late Regina Ridge, is not ‘Rydge’, although she appears here with both spellings; Eugene Goossens is not ‘Goosens’; the composer is Penderecki, not ‘Pendereski’; Rupert Murdoch’s daughter Elisabeth is named after her grandmother and is not ‘Elizabeth’; and it is Roberto Rossellini, not ‘Rosselini’. Such typos, irritating rather than ruinous, nevertheless take the edge off.

Comments powered by CComment