- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'Red Apple' by Phillip Deery

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is about a moral panic resulting in the deployment of huge police and bureaucratic resources to ruin the lives of some unlucky individuals who were, or seemed to be, Communist Party members or sympathisers. None of Deery’s cases seems to have been doing anything that posed an actual threat to the US government or population; that, at least, is how it looks in retrospect. But at the time the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the FBI judged otherwise and saw them as dangerous anti-democratic conspirators pledged to undermine, if not overthrow, the state. (Does any of this sound familiar?)

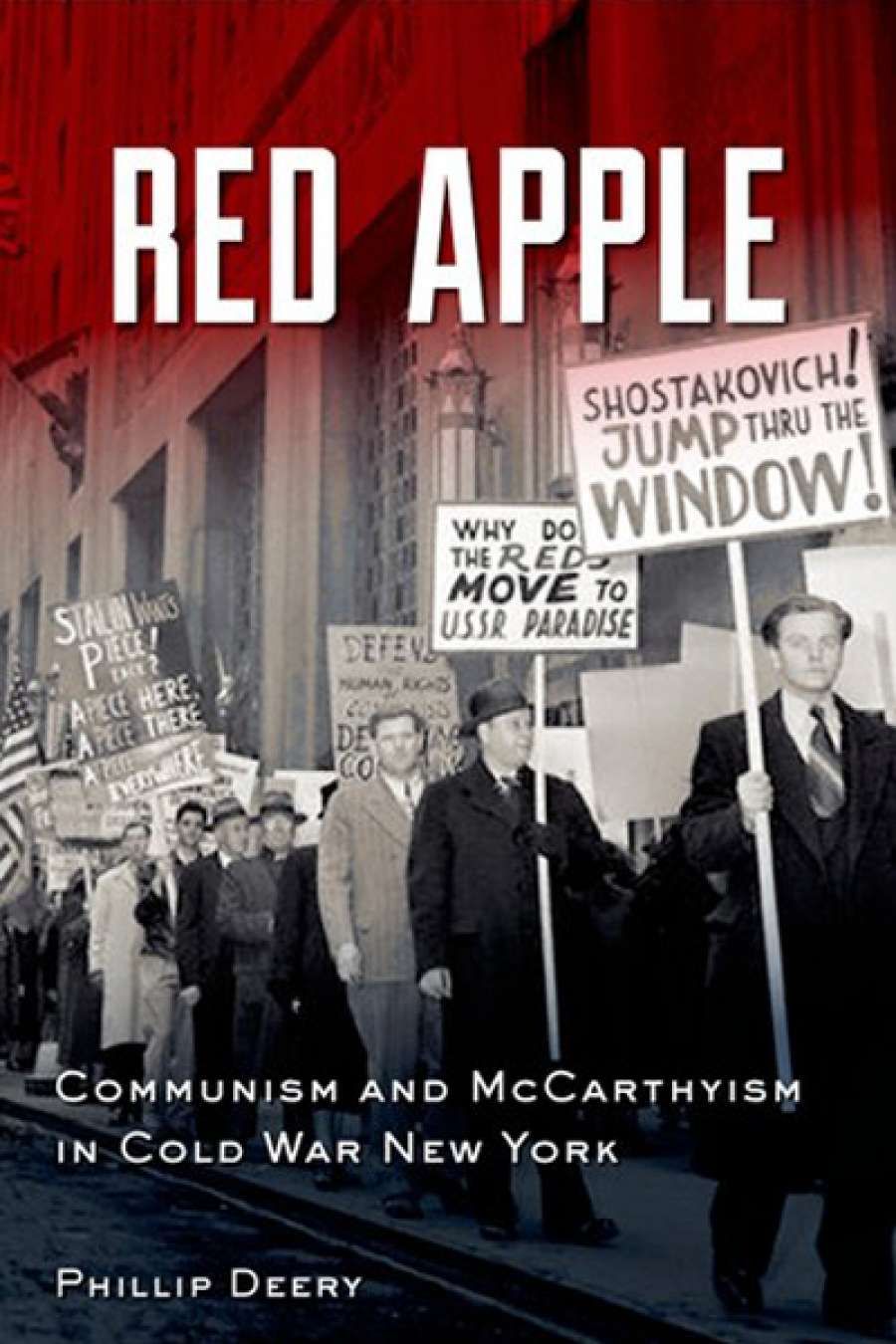

- Book 1 Title: Red Apple

- Book 1 Subtitle: Communism and Mccarthyism in Cold War New York

- Book 1 Biblio: Fordham University Press (OUP), $41.95 hb, 263 pp

Four of Phillip Deery’s five chapters deal with American victims of the anti-communist panic of the late 1940s and early 1950s: the surgeon Edward Barsky, the writer Howard Fast, New York University professors Lyman Bradley and Edwin Burgum, and the lawyer O. John Rogge. Most of them are linked by membership in the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC), an alleged communist ‘front’ organisation whose main interest, in fact, seems to have been helping anti-Franco refugees after the Spanish Civil War, particularly those in Mexico. The JAFRC motif is a useful organising device for the book. Another good decision of Deery’s was to complicate the familiar American story by introducing an outsider: the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, an unwilling member of the Soviet delegation to another ‘front’ organisation, the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace held at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York in 1949. (Deery, generally even-handed and judicious, calls suggestions of Soviet financing for this conference ‘fanciful’, but I wouldn’t be so sure: were the Soviets such laggards compared to the CIA that they didn’t give a little help to their friends?) Shostakovich and his fellow Soviet delegates were of course objects of suspicion to US authorities, but his victimisation came from other sources: on the one hand, the Soviet authorities, which the previous year had subjected him to harsh public criticism and now required him, as a delegate, to toe the party line and deny any resentment; and, on the other hand, anti-communist Western liberals who attacked him at the Waldorf conference as a Soviet mouthpiece.

Shostakovich was not a member of the Soviet Communist Party, though he would join – under pressure and against his better judgement – in 1960. Of the Americans, Barsky, Fast, and Burgum were party members; Bradley and Rogge not, but associated with causes that were also supported by communists. The conventional wisdom about ‘front’ organisations is that the front was a façade and the only thing that mattered was the communist presence behind. In the case of Barsky and JAFRC, however, this does not seem to be the case. While Barsky was a communist, his passion seems to have been for humanitarian work, first in Spain during the Civil War, where he worked as a surgeon at the front, and later looking after Spanish refugees through JAFRC. Called before HUAC, he and other board members, including Bradley and Fast, were judged to be in contempt for refusing to produce JAFRC’s books and foreign correspondence and were sentenced to three months’ imprisonment apiece.

One of the most depressing elements of the story is the eagerness with which people and institutions of which one might expect better, like universities and publishing houses, cooperated in persecution, often going far beyond what might be justified in terms of prudent self-interest. Lyman Bradley’s employer, New York University, was a private institution, and as such less vulnerable than state universities with their budgetary dependence on state legislatures. It had a past tradition of protecting academic freedom. All of this was forgotten when Bradley, an associate professor of German, was held in contempt of HUAC. The university suspended him without pay, and then, after he had served his short prison sentence, dismissed him. A year or so later, Edwin Burgum, an associate professor of English, suffered the same fate after being called before the Senate’s McCarran committee and taking the Fifth Amendment (against self-incrimination) on the question of Communist Party membership. The zealousness of NYU’s vice-chancellor in pursuing Burgum’s expulsion in 1952 was evidently related to the University’s ambitious building plan: if you need investment, you don’t rock the boat.

While terms like ‘saint’ were applied on the left to those victims like Barsky and Bradley, who took their punishment without changing their convictions, things were not always so simple. O. John Rogge, who had acted for JAFRC in its troubles with HUAC, was increasingly at odds with the pro-Soviet orthodoxy on the left, making himself unpopular by asking why the United States was blamed for everything and the Soviet Union for nothing. He started to find more common ground with friends in the State Department, and even the FBI, though as a lawyer he continued to defend civil liberties cases. The troubles of the bestselling author Howard Fast started when the New York Board of Education ordered his Citizen Tom Paine (1943) removed from public school libraries and publishers began to shun him. Later his books were removed from US Information Service libraries abroad along with those of other suspect writers, and in 1950 he was denied a passport. But Soviet anti-Semitism worried him from the early 1950s, and in 1957, after Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, he left the party. Both he and Rogge were savaged on the left as renegades.

Fast and Shostakovich are the true domestic and international celebrities on Deery’s list. Fast’s novels were as popular in the Soviet Union, where he earned substantial royalties, as they were in the United States. Shostakovich had had huge early success in the Soviet Union, propelling him into a privileged cultural élite. Condemnation of his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1936 was a career setback, but it did not dislodge him from his privileged position or lead to his arrest (though a number of his friends would be arrested in the Great Purges); and he was fully back in favour at home after his wartime Leningrad symphony, which also made him an international celebrity. Another career setback, though not a life-threatening one, came in 1948, which meant that his usual nervousness was accentuated at the Waldorf Conference.

Both Fast and Shostakovich can be seen as double victims, hit from the left as well as the right. At the same time, they were the two who, in career terms, survived their Cold War pillorying in comparatively good shape. Fast finally published his novel Spartacus in 1951, and his re-establishment in the United States was complete by the late 1950s, when Stanley Kubrick made it into a major motion picture. He was, of course, never forgiven in the Soviet Union. Shostakovich was not only confirmed in his status as top Soviet composer in the 1950s but also, by a strange quirk of fortune, became the darling of the post-Stalin Soviet intelligentsia as an articulator of their common suffering. In the West he was seen for a few decades as a Soviet hack, but then achieved posthumous liberal rehabilitation when Solomon Volkov’s dubious Testimony (1979) portrayed him as a quasi-dissident.

The lesser fry fared worse. Barsky lost his licence to practise medicine for a while, Bradley and Burgum never got back into academia or found solid ground outside, and Burgum’s wife committed suicide. When times changed in the United States, with the Great Society reforms of the 1960s, ‘the subjects of this book were demoralized, embittered, or no longer politically active’.

Comments powered by CComment