- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: James Walter reviews 'Triumph and Demise 'by Paul Kelly

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Paul Kelly’s considerable research ability, enviable political knowledge, narrative skill, and indulgence in polemics all figure in his new book. The former qualities make it a must-read for the politically engaged; the latter is so pronounced that such readers may succumb to frustration and throw the book at the wall before reaching the valuable final chapter where at last we arrive at a coherent account of the systemic roots of ‘the Australian crisis’.

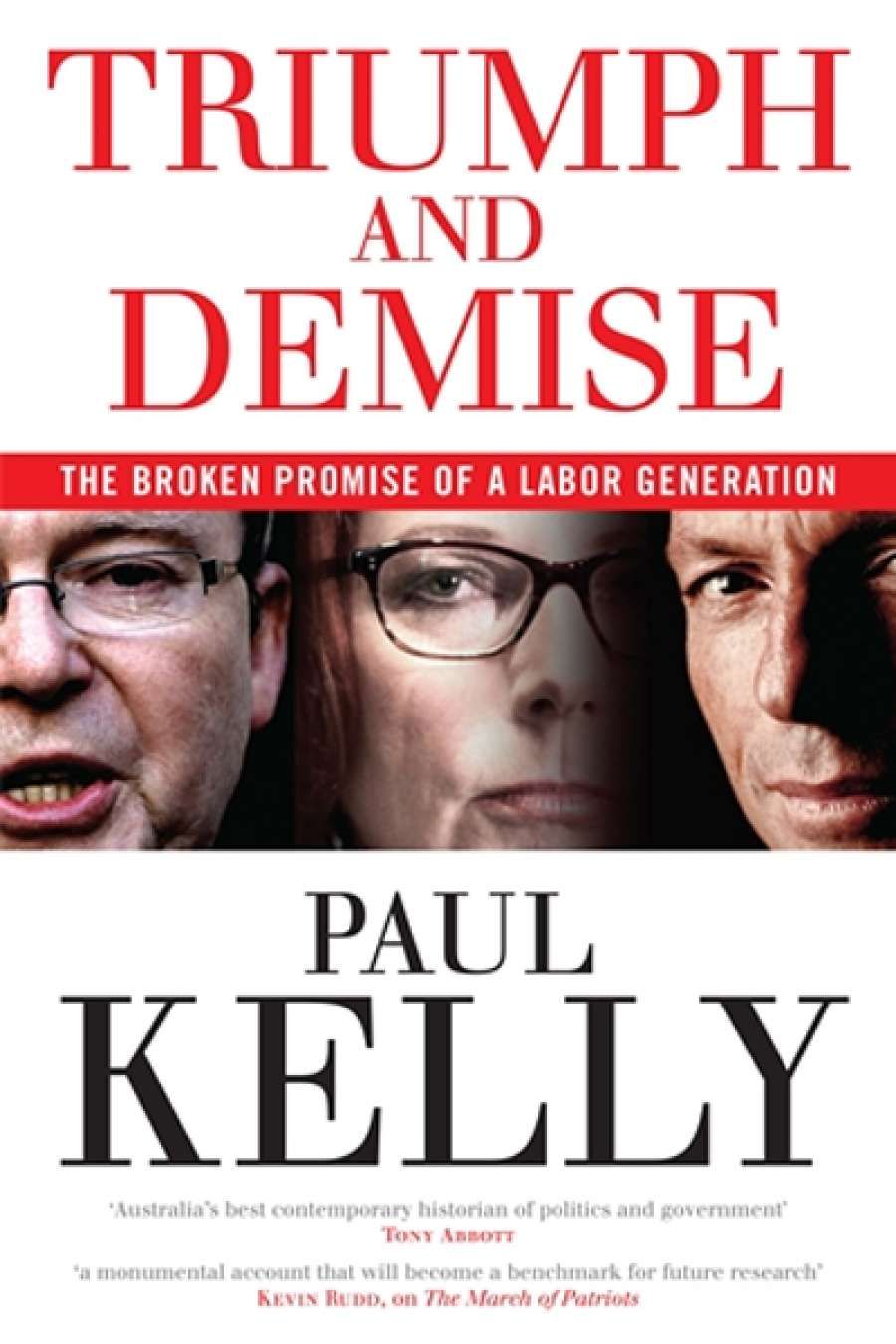

- Book 1 Title: Triumph and Demise

- Book 1 Subtitle: The broken promise of a Labor generation

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $49.99 hb, 560 pp

Kelly’s dissection of the failures of the Rudd and Gillard governments complements his earlier works, The End of Certainty: Power, Politics and Business in Australia (1992) and The March of the Patriots: The Struggle for Modern Australia (2009). These celebrated heroic economic policy reform between the 1980s and, roughly, 2004. The question then is: having done so well, how did it come to this? Much of Kelly’s discussion – as is the case in contemporary commentary more broadly – centres on the capacities of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, and their relations with each other, colleagues and subordinates, the policy community, the party, and the public.

Many books – by participants, biographers, and journalists – were rushed out following the Rudd–Gillard ‘demise’, including Gillard’s own memoirs. Kelly reveals little that could not be gleaned from other sources, but the advantage of his work is that of the accomplished researcher: with the detailed knowledge that provides context, he has interviewed all the major players (including Rudd), and synthesises competing accounts plausibly, giving us the nuance that others have missed. Thus, while his version of what happened in the days before Rudd’s deposition by Gillard is broadly in accord with her own, it incorporates a range of perspectives that illuminate where she is disingenuous or self-deceiving. Equally, Kelly reminds us of what many have forgotten: that Rudd and Gillard sold themselves to their party as a package, and that for three years, in the run up to the 2007 election and well into Rudd’s initial term, the partnership worked effectively.

Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd at their first press conference as deputy leader and leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006. (photograph by Adam Carr)

Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd at their first press conference as deputy leader and leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006. (photograph by Adam Carr)

Much will be made of what is said to be Kelly’s ‘forensic’ attention to detail. In some instances this is compelling. His interpretation of the collapse of the Gillard government’s ‘Malaysia solution’ to the problem of asylum seekers, for example, is very good. It underlines the laziness of commentary that dismissed it as simply another example of hasty conception and disregard for due diligence. On the other hand, Kelly has his own investment in climate change policies – I will return to this – and if forensic detail is what you want, Philip Chubb’s even more closely researched Power Failure: The Inside Story of Climate Politics under Rudd and Gillard (2014) is more informative and incisively analytical.

Kelly’s argument, at least to the end of the penultimate chapter, is that the failure of reform ‘is really the responsibility of Rudd and Gillard … [Their] generation underperformed … It should have governed better and for longer … The Rudd–Gillard leadership rupture ruined the government.’ In conjunction, he insists that ‘disastrous policy problems in relation to climate change, economic reform, the mining tax, budget management and sustainability, boats policy and hospitals policy’ demonstrate that their policy framework was fatally flawed.

Pairing such assertions begs the question: was it disastrous leadership or flawed policy that sank the reform agenda? Surely it could be both, but Kelly’s propensity for ringing declarative sentences suggests at first one thing, then the other. Kelly sidesteps such conundrums in the final chapter by turning to the systemic problems of contemporary politics: ‘the Australian crisis’ is that ‘the business of politics is too decoupled from the interests of Australia and its citizens’. Why? The erosion of political culture, the decline of the parties, the obsession with polls, the relentless media cycle, the descent into a combat politics that has destroyed the cross-party consensus essential for reform, the failure of communication between the political class and the community – all of these, he concedes, have made ‘the pivotal factor’, leadership, nigh on impossible: ‘it is by no means certain that Bob Hawke and Paul Keating would have succeeded in the contemporary system.’

There is much to reflect on, and to argue with, in this final chapter, but it is only here that a narrative that has been plausible in particulars but perplexing in overview finally seems coherent. The problems that bedevil the book as a whole are twofold. The first is Kelly’s proclivity for delivering an ‘as it happened’ narrative with a relentless barrage of opinionated judgement; the second, his unacknowledged investment in a specific, narrow formulation of the reform agenda.

Kelly cannot allow his material to speak for itself. Scarcely a page passes without some ex-cathedra pronouncement on the failures of his protagonists. This is what frustrates: the flow is interrupted as the reader is badgered, told what to think. It is also curiously inconsistent. Early in the book, Gillard’s deposition of Rudd is the death warrant of the Labor government: ‘By her action, Gillard assumed responsibility for the consequences.’ But then, most attention is given to Rudd’s failures in government (twenty-one of the book’s thirty-three chapters), reflecting what Gillard has argued: that he was impossible and eventually dysfunctional, leading to another verdict – ‘A competent prime minister would not have been deposed. Rudd was removed by a groundswell of personal animosity and mass panic … [He] faltered at his point of supposed policy strength: as a policy leader … the caucus lost faith.’ In the end, as noted above, Kelly holds Rudd and Gillard jointly responsible, then temporises by conceding ‘The Labor government was broken by the pressures of the system.’

This is of a piece with veering from one statement to another on the causes of Gillard’s ‘ruin’. On page 430: ‘In the end, Western Sydney would ruin Gillard.’ Then again, on page 456, ‘It was the polls that ruined Gillard.’ By page 467 it is feminism: ‘The feminist/misogyny tactic was a tragic false step.’ An approach less given to hyperbole would temper such definitive statements, carefully assessing how factors operated in concert. It reminds me irresistibly of Roy and HG calling the AFL final: every development in the game described as the ‘killer’ move, only to be succeeded by another, moments later, with a delirious dénouement when all inconsistencies are swept aside in a final, hectoring, Olympian overview.

Kelly’s hectoring in the end is about us: our failure to recognise the obvious. ‘Australia’s worst delusion,’ for instance, ‘is that because it has no economic crisis it has no political crisis.’ Above all, it is about our failure to engage with the unfinished business of economic reform. He allows only one framing of the future agenda, refusing to acknowledge the crises now besetting global market economics, or to grant credence to alternative views. The witnesses he calls to testify about what went wrong and what now must be done are from the big business councils. Dissident economists, the churches, social services, and community activists are conspicuously absent: they have no grasp of the national interest. Kelly alone speaks for hard-headed economic realism.

Early in the book, Kelly provides a fair reading of Ross Garnaut’s climate change reports and describes Garnaut as the ‘guardian of the reformist creed’. But in his extended chapter on Gillard’s mishandling of climate policy, not only is science missing, but he also ignores policy entrepreneurs once central to his faith, such as Garnaut, Hawke’s adviser, who has continued to adapt to changing circumstances. Hence the difficulty with Kelly’s representation of climate politics: Garnaut (as did Nicholas Stern) presents climate change as the fundamental reform challenge for the maintenance of viable economies, and identifies the business leaders on whom Kelly relies as the obstructionist rent seekers of our time. Arguably, it is undue deference to their opinion that has produced what an adviser to Angela Merkel (hardly a radical) recently described as ‘the suicide note’ for the Australian economy: is this, instead, ‘the Australian crisis’?

Comments powered by CComment