- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Nature Writing

- Custom Article Title: Jane Goodall reviews 'The Lake's Apprentice' by Annamaria Weldon

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Samuel Johnson had some advice for aspiring writers. ‘Read over your compositions,’ he said, ‘and where ever you meet with a passage which you think is particularly fine, strike it out.’ One imagines the impact of this recommendation on an eighteenth-century student of literature, clutching a page of overblown rhetorical flourishes and faux erudition. Our crimes of vanity in writing are very different now – more likely to take the form of descriptive tours de force of the kind fostered in creative writing classes.

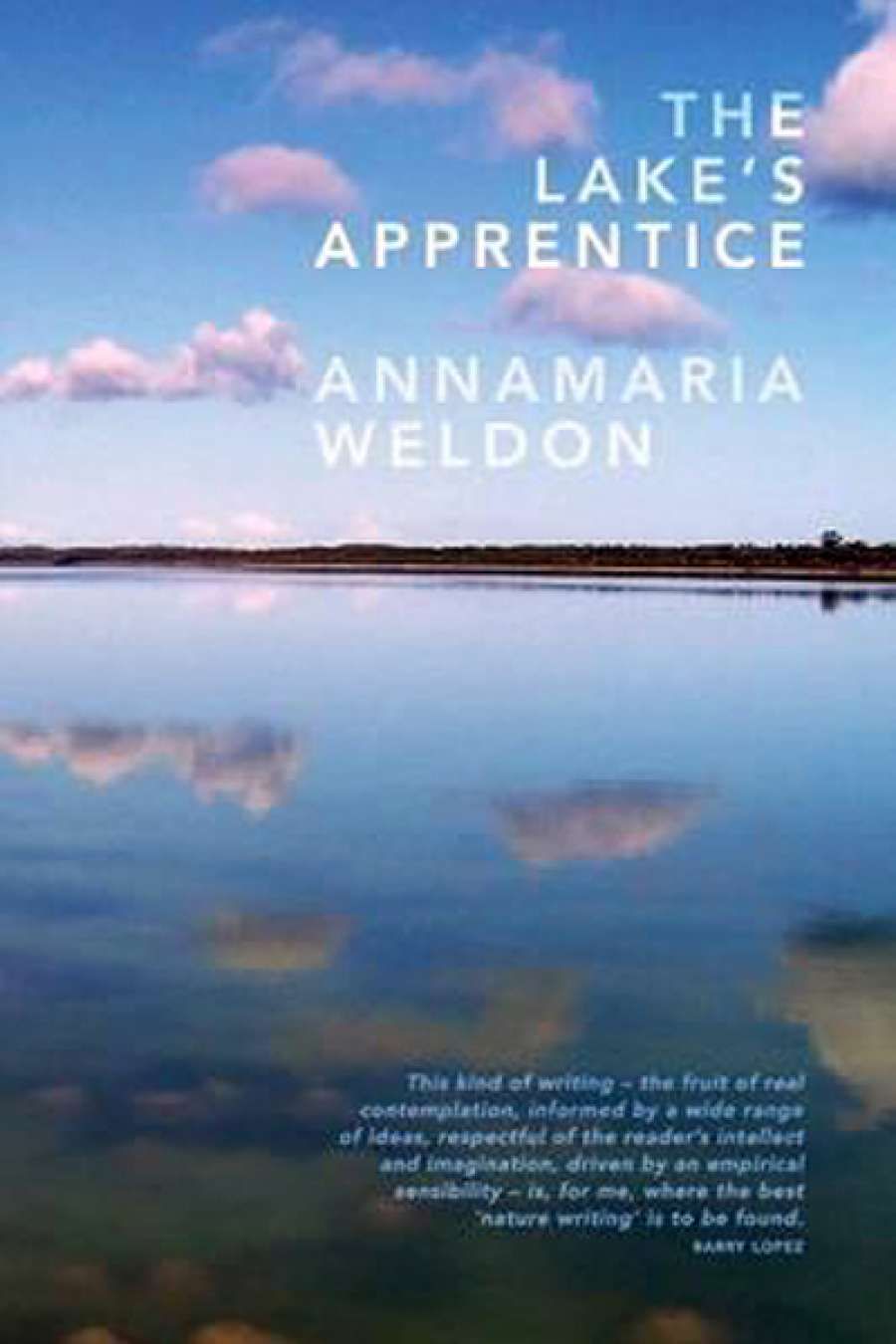

- Book 1 Title: The Lake's Apprentice

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.99 pb, 245 pp

Johnson’s stern medicine is perhaps nowhere more acutely required than in the area we call ‘nature writing.’ It was a common or garden practice in Johnson’s time, usually consigned to small scribbled notebooks that were put away in a drawer when they were full; but now we have residencies, grants, and prizes for it. Some of our most revered literary figures are known for it. Everyone, it seems, wants to be Annie Dillard, and quotations from her work are introduced to serve as dynamic lifter for the surrounding text.

Well, what’s wrong with that? Dillard is herself a stern influence. She offers a model of austere writerly discipline and also of a self-effacing, almost puritanical approach to being-in-the-world. Annamaria Weldon, who readily acknowledges the Dillard influence in The Lake’s Apprentice, also acknowledges that nature writing presents an especial challenge to the sense of self. Her opening poem is prefaced by a quotation from Mark Tredinnick’s The Blue Plateau: ‘There is a practice of belonging and it starts with forgetfulness of self.’

Weldon’s title, The Lake’s Apprentice, implies this kind of practice. It is a long-term commitment, undertaken, in her case, over five years, beginning with a 2009 artist’s residency at Lake Clifton in the Yalgorup National Park in Western Australia. The book is a collection of poems, photographs, and journal writings about the Lake and its biosphere, drawn from observations made in all seasons with the guidance of traditional owners. None of it has come easy. It takes some stoicism to put up with hours lying amid tick-infested brush to get the right angle on a photograph, sitting in a cold wind to watch birds take off in the dawn light, walking uphill in dense scrub.

The results are, in places, arresting. There are some wonderful photographs – textural close-ups, wide-angled panoramas, abstract studies of light on water. The best of the poems seem to almost lift off the page like the birds they describe. And yes, there are some ‘particularly fine’ examples of word craft. Black swans flying in low at dusk ‘look like long black stitches which night gathers to its shore’. The Nullaki Peninsula is ‘folded like a hinge between two skies’. Should a writer really strike out such things?

Of course not, and yet there is a trap here. Call it the vanity trap, and it makes its catch when the wrong kind of self comes hovering into the foreground, seeking attention. The second of the images I have just quoted is included in a prefatory piece called ‘The Practice of Belonging’ and is actually italicised as one of the ‘best lines’ gifted to her by the place she sets out to evoke. Elsewhere, Weldon chooses quotations from her own work as epigraphs.

Picking your own best lines is a habit that will definitely lead you into the trap. It cultivates a self-consciousness about effect, an overvaluation of composition at the level of the word. Writing has its own geologies, and paying too much attention to the surface can lead to an inattention to the deeper layers. This is where Dillard excels. All her works, however long or short, have deep thematic substrata. There is granite down there, and it may glint when the light hits it, but its formations are not to be easily played with.

The Lake’s Apprentice is an assembly of texts held together by a potent spirit of place, but there is a lack of craft in their formation as individual pieces, and the book as a whole is deficient in connective tissue. Recurring images and narrative points that form the through-lines come across as repetition rather than development.

Lake Clifton, Western Australia (photograph by Sean Mack, 2008)

Lake Clifton, Western Australia (photograph by Sean Mack, 2008)

Weldon’s account of the loss of her connection to country in her native Malta, and the slow formation of a new bond with the land as an Australian immigrant might have been linked with some wider reflections on the fundamental divide between indigenous and settler relationships to the land.

The dominant symbolic element in the book is the presence in Lake Clifton of thrombolite colonies, primordial egg-like stones that harbour dense colonies of microbacteria; they actually breathe, and are credited with producing the oxygen that originally made the environment habitable for mammalian life. There is a potent association with indigenous creation stories, and a range of geological and biological analysis to draw on, but the exploration of this material lacks depth and determination.

Perhaps the apprenticeship, long as it may already seem, has not been long enough. The lure of getting a book out there may conflict with the more nebulous project of developing a timeless relationship with a place that is redolent with its own forms of poetry and story.

Comments powered by CComment