- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

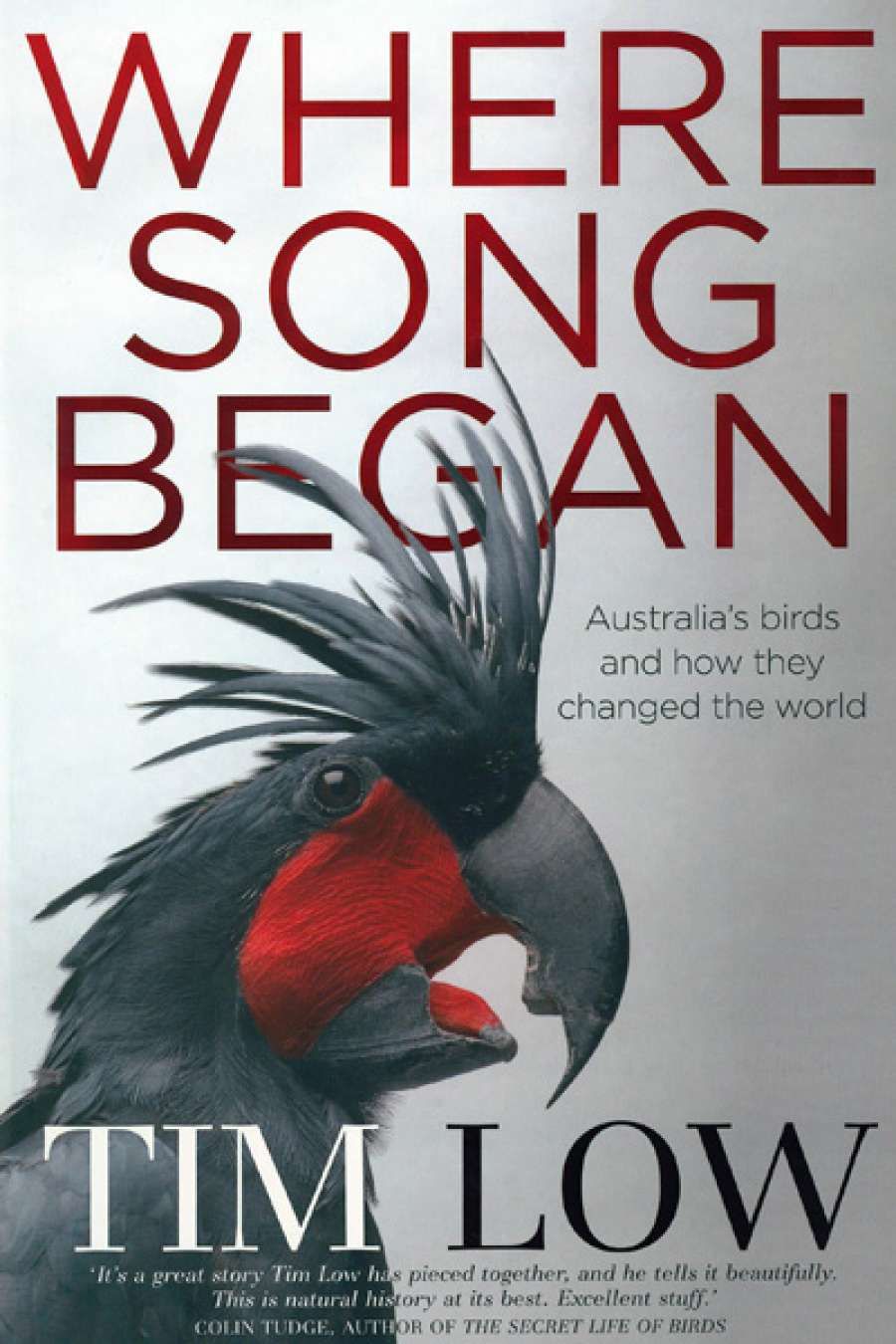

- Custom Article Title: Peter Menkhorst reviews 'Where Song Began' by Tim Low

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia’s birds stand out from the global avian pack in many ways – ecologically, behaviourally, because some ancient lineages survive here, and because many species are endemic. The ancestors of more than half of the planet’s ten thousand bird species (the songbirds) evolved right here (eastern Gondwana) before spreading across the world. Indeed, Tim Low claims in this important and illuminating book that Australia’s bird fauna is at least as exceptional as our mammal fauna, which has such remarkable elements as the egg-laying monotremes (platypus, echidna) and our marvellous radiation of marsupials (kangaroos, quolls, bandicoots, possums, etc.). Can this be so? As a mammologist, my initial response was that Low’s claim is a bit rich, but, after reading this book, I take his point.

- Book 1 Title: Where Song Began

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia's birds and how they changed the world

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $32.95 pb, 406 pp

One would have thought that Australia’s birds were already well known and understood. Of the many books on the subject, none has had the impact on this reviewer of Where Song Began. Tim Low is one of Australia’s best natural history writers. Here he has collated, digested, and interpreted a huge volume of recent scientific literature and meshed it with insights derived from the historical literature and his personal travels. The book is really a series of essays about disparate aspects of Australia’s bird fauna: how it differs from those of other continents; why those differences arose; the significant role of this continent in bird zoogeography and evolution; and the critical function of birds in Australian ecosystems, particularly as pollinators, pest controllers, and dispersal agents. In the final chapter, the varied relationships between Australians and our birdlife are thoughtfully examined.

The last few decades have been an exciting time for students of Australian birds. The rate of accumulation of knowledge, due partly to the incredible advances in genetic technologies, has made it difficult to keep up, even for professionals. This book provides a brilliant entry to this new world in which traditional northern hemisphere views about bird evolution and the colonisation of Australia by birds have literally been turned on their head.

But birds cannot be understood in isolation from their environment. Low’s background in botany and ecology shines throughout as he interprets how Australia’s constantly changing environment has channelled bird evolution and behaviour down particular and sometimes unique paths. He rightly points out that New Guinea is biogeographically as much a part of Australia as is Tasmania, both having been regularly connected to the continent during glacial maxima when sea levels were lower.

For example, the two Straits – Torres and Bass – were absent for the 90,000 years prior to 11,000 years ago, allowing ample time for extensive faunal and floral exchange. And there has been considerable species exchange in both directions, as exemplified by our crested bellbird, which inhabits dry, semi-arid scrub and mallee; its closest living relative, the rufous-naped bellbird, lives in high-altitude rainforest in New Guinea. Presumably, their shared ancestor inhabited rainforest because Australia’s dry lands are a recent development (about six million years ago). The proto-crested bellbird, stranded on Australia, had to adapt to drying conditions, while the New Guinea form has continued to enjoy its montane rainforest habitat.

An illuminating opening chapter considers why species that are large, aggressive, raucous, and often brightly coloured tend to dominate Australian bird communities. Low links these trends to our ancient continent, with its leached, infertile soils and unpredictable, but mostly sunny, climate. Our vast forests, woodlands, and tropical savannahs are dominated by sclerophyll vegetation (notably the genus Eucalyptus and its close relatives), which does not give up its nutrients easily – the leaves offer little nutrition, seeds are enclosed in woody capsules that require bolt-cutter beaks to open, and fruits are rare.

The rose-crowned fruit-dove which is common in northern Australia

The rose-crowned fruit-dove which is common in northern Australia

Instead, our trees and shrubs exude carbohydrates in the form of nectar, honeydew, and lerp. This massive sugar resource is avidly exploited by our fauna, including insects, mammals, and birds – notably the honeyeaters. Honeyeaters form Australia’s largest bird family (with sixty-nine species in Australia and another fifty or so in New Guinea) and dominate Australian bird communities in diversity, number, and behaviour. They are almost constantly alert, active, belligerent, noisy, and communal, ganging up on competitors and threats – a whole bird community with attitude (attention deficit disorder?), powered by plant sugars. There is nothing comparable elsewhere.

After feeding on nectar, birds often carry a dusting of pollen on the feathers of their forehead. Some of these pollen grains may be deposited on the flower of another plant and fertilisation may ensue. Low’s thoughts about the potential spatial scale of this process are fascinating – could the migratory and nectarivorous swift parrot be the vector responsible for genetic exchange between blue gums in southern Victoria and those in eastern Tasmania?

In his introduction, Low states that he has adopted an informal and conversational language, but one chosen with enough care that he feels safe in inviting scientists to trust it. My judgement is that he has succeeded admirably, although occasionally I winced at what seemed like over-reaching towards populism, such as replacing the adjective ‘nectarivorous’ with the adjectival noun, ‘nectar bird’. But these are matters of personal taste – the message remains accurate. The detailed referencing and bibliography will help the reader to clarify any uncertainties resulting from the informal language.

Far from being yet another book about Australian birds, Tim Low has produced an original, quirky, and thought-provoking overview of Australia’s bird fauna, actually of Australia’s biota, aimed at a general readership. Importantly, he has achieved this with scientific validity intact. Read it and change the way you look at the Australian bush and its inhabitants.

Comments powered by CComment