- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Dina Ross reviews 'Jean Galbraith' by Meredith Fletcher

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

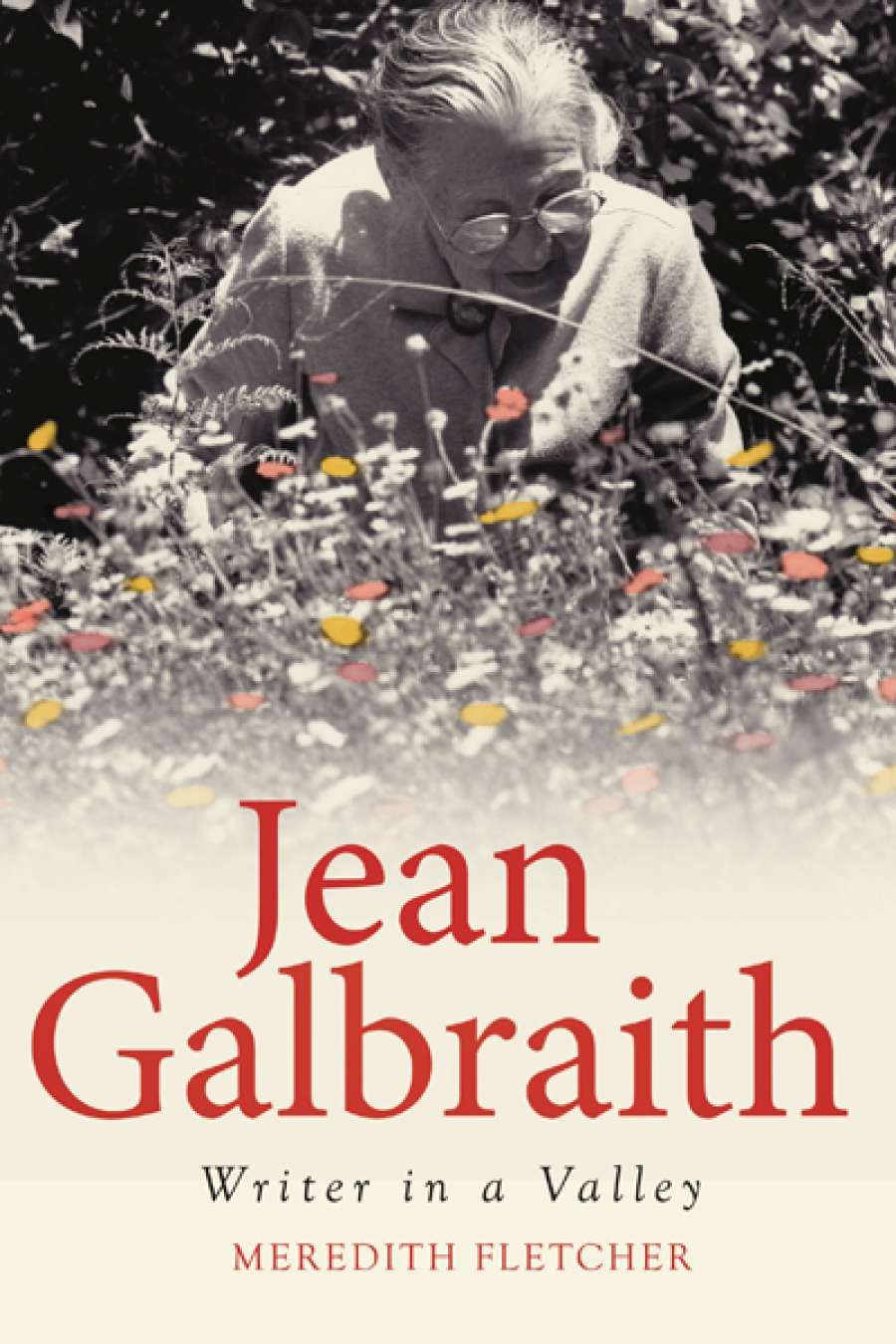

The last photographs taken of Jean Galbraith show a wrinkled woman in her eighties, with wispy hair pulled back in a bun, wearing round tortoiseshell spectacles, thick stockings, and sensible shoes – the kind of person you might expect to see serving behind the counter of a country post office early last century, or pouring endless cups of tea at church fêtes. Yet her unprepossessing appearance belied the extraordinary woman within. For Australian nature lovers and botanists, Jean Galbraith was an icon. Over the seventy years of her writing career (her last article was published when she was eighty-nine), she turned botanical writing into an art form, branched into television and radio scriptwriting, wrote children’s books, lectured tirelessly on the beauty of Australia’s native flora, and became a fierce advocate for conservation. When she died in 1999, aged ninety-two, she had earned many awards and accolades, including the prestigious Australian Natural History Medallion.

- Book 1 Title: Jean Galbraith

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writer in a valley

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 292 pp

Jean Galbraith was not born into a family of botanists or academics. Her forebears and parents were bakers and farmers who emigrated from Scotland in the 1870s to settle in the lush valleys in Gippsland, Victoria. Bounded by the foothills of the Great Dividing Range to the north and the Strzelecki Ranges to the south, Jean’s childhood was spent in a magical landscape of wildflowers and rich pasture, with the bush close by. She described it as ‘the very fabric of my being’. From an early age she collected and grew plants and flowers in her garden, painting and writing about them in notebooks. A shy, near-sighted child who suffered from asthma and eczema, she spent much of her time at home.

The Australian Garden Lover, December 1926 (State Library of Victoria)

The Australian Garden Lover, December 1926 (State Library of Victoria)

Writing came naturally, an escape from loneliness. Her first article appeared in The Leader when she was thirteen. By sixteen, as an active member of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria, she was assisting the organiser of the FNCV, H.B. Williamson, at the annual wildflower show at Melbourne Town Hall. With Williamson as mentor, Galbraith met other enthusiasts and greatly increased her understanding of Australian flora. Her appetite for knowledge was voracious. Soon she was contributing articles to the Victorian Naturalist magazine and was involved with other horticultural societies as a botanist. At the same time, she redesigned the layout of the family garden. She was keen to use Australian natives as well as exotics, which distinguished her garden from others of the period. Her garden boasted roses, wildflower borders, various wattle species including an early black wattle, an orchard with nut trees, cherry, peach, apple and quince, and a vegetable garden. Over the years she rejoiced in the riot of colour ‘dancing’ along her sweeping lawns. Her garden became both a passion and an inspiration for much of her subsequent writing.

In 1925, aged nineteen, Galbraith began contributing articles under the pen name ‘Correa’ to the monthly Garden Lover magazine. Australia did not have a strong tradition of nature writing until then, and Galbraith was one of its pioneers. Here is an example of her style: ‘Orange twigs and ruby stems threaded the maze of leaves, and, in a mystery of colour, yellow deepened into green and crimson ... Tremulous globes of silver and spots of shrill white fire threw lances jewel bright across the air.’ Her poetry and lyricism enchanted her readers, bringing a uniquely feminine perspective to a literature that had been hitherto dominated by men.

By her mid-twenties, Galbraith was a garden and nature writer, a botanist developing expertise in Australian flora, and an experienced gardener. She was also the daughter who stayed home, caring for relatives as they aged. It was a role she adopted willingly. Galbraith was never romantically linked – her most extensive correspondence as a young woman was with the nature writer John Lothian, then in his seventies.

As Galbraith’s confidence grew, she began publishing in other venues. She also became a committed conservationist. She wrote forceful articles, leading to laws being passed protecting many of Victoria’s wildflowers. In the 1950s, she liaised with the State Electricity Commission, other public utilities, and Premier Henry Bolte to protect vast areas of bushland under threat of industrial development, with mixed success. A measured campaigner, she sought the difficult middle ground of ‘balanced development’, with conservation at its heart.

Galbraith’s best-known work, Garden in a Valley, a collection of her articles amalgamated into book form, was first published in 1939. It was given a lukewarm response and only received true recognition many years later. When the book was reprinted in 1985, a bemused Galbraith suddenly found herself famous. Visitors flocked to the gentle octogenarian’s home, and she welcomed them to her garden.

Galbraith wrote several other books, including a field guide to Australian wildflowers – no mean feat, as there are more than twelve thousand species in Western Australia alone. She particularly enjoyed writing for children. Her ‘Grandma Honeypot’ nature stories, first recorded for the ABC, became children’s favourites in the 1960s and were collected in a book by Angus & Robertson.

Environmental historian and researcher Meredith Fletcher, an adjunct research fellow at Monash University, brings a great deal of warmth and admiration to Galbraith’s biography. She turns a quiet, scholarly, modest existence into a book that breathes real life into its subject and celebrates the uniqueness of a Victorian landscape threatened by the modern world.

Comments powered by CComment