- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Asian Studies

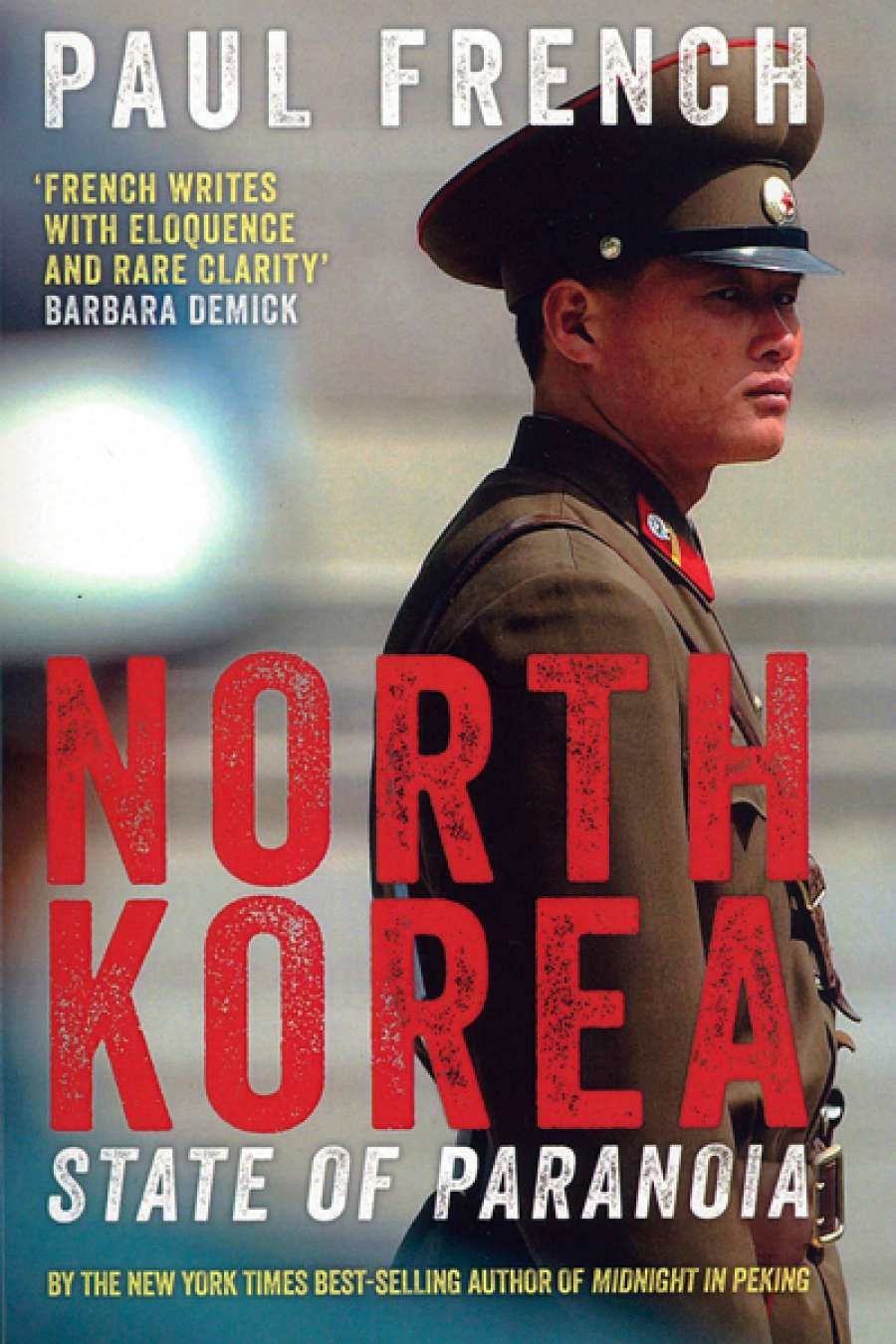

- Custom Article Title: Richard Broinowski reviews 'North Korea: State of paranoia' by Paul French

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nuclear weapons as parley

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

North Korea always gets media attention for negative reasons: a border skirmish with its southern neighbour; a missile trial launch or nuclear test; vitriolic propaganda attacks on South Korea, Japan, or the United States; or the appalling findings of some human rights group like Michael Kirby’s recent UN Commission of Inquiry on North Korea’s human rights abuses. The picture that emerges is one of unrelenting misery within North Korea and unreasoned aggressiveness towards its enemies – a dangerous and unpredictable country which, if it cannot be reformed, is best either shunned or guarded against.

- Book 1 Title: North Korea

- Book 1 Subtitle: State of paranoia

- Book 1 Biblio: ZED Books, $26.95 pb, 478 pp

Unrelenting misery is not, of course, the whole story. As film-maker Anna Broinowski (my daughter) shows in her documentary Aim High in Creation (2014), at least seventeen million North Koreans live fairly ordinary lives. They are not locked up, and unless there is a long drought or violent flood causing crop failure, they don’t die of starvation. However, according to the United Nations, malnutrition is widespread. There is also a lively and inventive film industry which seeks, within the limits of technological capacity and ideological constraints, to emulate the achievements of that of South Korea.

Like Broinowski, Paul French attempts to humanise the country, or at least Pyongyang. In the opening chapter of his North Korea: State of Paranoia, he describes the basic but liveable city apartment blocks hastily thrown up after the Korean War, during which the city was comprehensively flattened. Canteens serve adequate meals to workers, clothing is generally available – make-up too. The owners of the few private cars are fined if their cars are dirty, or if they smoke while driving. Traffic lights are turned off to save power, and young women chosen for their beauty direct traffic. But electricity supply is uncertain, there is little or no heating in winter, and lifts and lights don’t always work. Inhabitants too poor to be able to afford a Japanese-made ‘Seagull’ bicycle take overcrowded buses or walk, mainly walk. There are very few obese people in Pyongyang, or indeed, in the whole country.

French goes on to provide a lucid and comprehensive account of the Juche state, the very Korean fusion of Marxism–Leninism and Confucianism, under which the three Kims – Il-sung (1948–94), Jong-il (1994–2011) and Jong-un (since 2011) – have each succeeded in exerting iron control over the State. In the 1960s, the North had seventy-five per cent of the peninsula’s mines, ninety per cent of its electric generation, eighty per cent of its manufacturing plants, and was wealthier than South Korea in GDP. Kim Il-sung promised that everyone would soon wear silk, live in houses with tiled roofs, and eat three square meals a day.

Metro in Pyongyang (photograph by David Eerdman)

Metro in Pyongyang (photograph by David Eerdman)

None of these dreams eventuated, and that is why North Korea, under its current ruler, may be capable of entertaining perestroika (ending central planning), but never of embracing glasnost (increasing openness and transparency in government). To be open would mean admitting massive economic failure and would destroy the myth of the Kims’ invincibility.

By 1975 the DPRK had virtually declared itself bankrupt with an external debt of $5.2 billion. Its labour reserves were dwindling, its research and development were increasingly confined to the military sector, and corruption and under-performance were rife in state-owned enterprises. Quality failures in light industries occurred more often, and economic incentives to stimulate the agricultural sector to alleviate food shortfalls were not permitted. Other countries, including North Korea’s only friend, China, were loath to invest in what was rapidly becoming a basket case. Free-trade zones at Sinǔiju and Rajin-Sŏnbong lost impetus as investment was always too little, too late. Free traders at Kaesŏng struggle on, but without much conviction.

French rightly observes that a chronic national power shortage contributed to the economic malaise. When drought reduced the output from hydroelectric plants between 1990 and 1999, and antiquated thermal plants were not replaced, generating capacity dropped by forty per cent. No power meant no fertiliser, a lack of food, stoppages of Soviet-inspired heavy industries like cement and steel plants, and general economic torpor.

Half-hearted economic reforms were attempted. Prices were adjusted, the currency was devalued against the American dollar, farmers’ markets similar to the Cuban agropecuarios were permitted, small businesses and restaurants similar to Havana’s cuentapropistas opened. Nothing worked because free-enterprise innovation was thwarted by massive state interference.

The year 2002 was supposed to be the year of recuperation. Instead, food shortages reached famine proportions and growing numbers of defectors fled to China. Internal economic agonies were compounded by an increase in foreign censure. South Korean president Kim Dae-jung’s ‘Sunshine’ policy of reconciliation faltered, and President George W. Bush lumped North Korea together with Iraq and Iran as ‘rogue states’. To cynical outside observers, there were two ways the régime could die – either by reforming itself, or by not reforming itself.

French, however, highlights a much-overlooked fact: that at various stages since the Korean War both North Korea and its antagonists have tried to reconcile their differences and develop normal relations. A flurry of North–South engagements in the early 1970s led to a North–South Joint Communique between Kim Il-sung and Park Chung-hee in which both sides agreed to stop slandering each other and reunify the country peacefully without outside interference. When parts of the ROK were flooded in September 1984, Pyongyang offered relief assistance which Seoul accepted. In the early 1980s, thirteen rounds of bilateral economic talks were held, and in September 1985 a series of family reunions were arranged.

Jimmy Carter (photograph by the Naval Photographic Centre)

Jimmy Carter (photograph by the Naval Photographic Centre)

Two unlikely envoys, Billy Graham and Jimmy Carter, visited Pyongyang on behalf of President Clinton in 1993. Their endeavours led to the 1994 Framework Agreement under which South Korea, Japan, and the United States would build two ‘proliferation resistant’ 1000-MW light water nuclear reactors to alleviate North Korea’s power shortage, and supply bunker oil during their construction. In exchange, North Korea would close down its own nuclear reactor, which was generating plutonium for its nuclear weapons program, stop trying to enrich uranium, adhere to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and allow IAEA inspections of its nuclear facilities. Former Defence Secretary William Perry visited Pyongyang in May 1999, Vice Marshal Jo Myong-rok went to Washington in October 2000, Foreign Secretary Madeleine Albright to Pyongyang a month later. ROK president Kim Dae-jung visited Pyongyang in June 2000, as did Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in October 2002.

For some years, especially after negotiation of the 1994 Framework, North Korea cooperated in nuclear matters. It gave American engineers free run of its nuclear facility at Yongbyon, and allowed the dismantling of some nuclear facilities. But it became clear towards the end of Clinton’s term in 2001 that a recalcitrant US Senate would not allow the supply of reactors, and the attitude of Pyongyang soured.

In the introduction to his book, French makes the valid point – frequently overlooked or ignored by Western propagandists – that it was the Americans, not the North Koreans, who caused North Korea to return to their nuclear weapons program. The result, three nuclear tests and several ballistic missile firings, have underlined North Korea’s determination to develop its capacity as an effective nuclear weapons state. With some justification, Pyongyang argues that it is the only guarantee it has to deter its enemies from attacking it with nuclear weapons or bringing about a régime change.

Pyongyang’s weapons program is also a plea for attention. French quotes Kim Jong-il as saying in 2003 that ‘The missiles cannot reach the US, and if I launch them, the US will fire back thousands and we would not survive. I know that very well. But I have to let them know that I have missiles. I am making them because only then will the US talk to me.’

That has been the mindset of all three Kims. Despite the indefinite postponement of Six Party Talks between Beijing, Washington, Seoul, Tokyo, Moscow, and Pyongyang, negotiation continues to be the only way of mitigating confrontation and heading off dangerous clashes on the Korean peninsula, especially between the United States and the DPRK. French knows this, and his well-researched book underlines the point many times. It belongs, in rare company, on the same shelf as the enlightened works of the American academic Bruce Cumings.

Comments powered by CComment