- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a long tradition of physicians turned writers, including Chekhov, Keats, Conan Doyle, and Somerset Maugham. More recent doctor–novelists include Alexander McCall Smith, Michael Crichton, and Khaled Hosseini. In Australia, Peter Goldsworthy is probably our most prominent writer–physician, with John Murray and now Paul Komesaroff joining the tradition.

Medicine provides plenty of material for the novelist. As Peter Goldsworthy said in an interview in the Medical Journal of Australia: ‘You can’t write a novel unless you have constant human contact – talking to people, listening to what they say, and studying their character – medicine’s perfect for that.’ A medical practitioner sees diverse people, often in crisis. They watch relationships change, and fail to change. They witness messy storylines being played out in front of them. They confront birth and death, disease and desire.

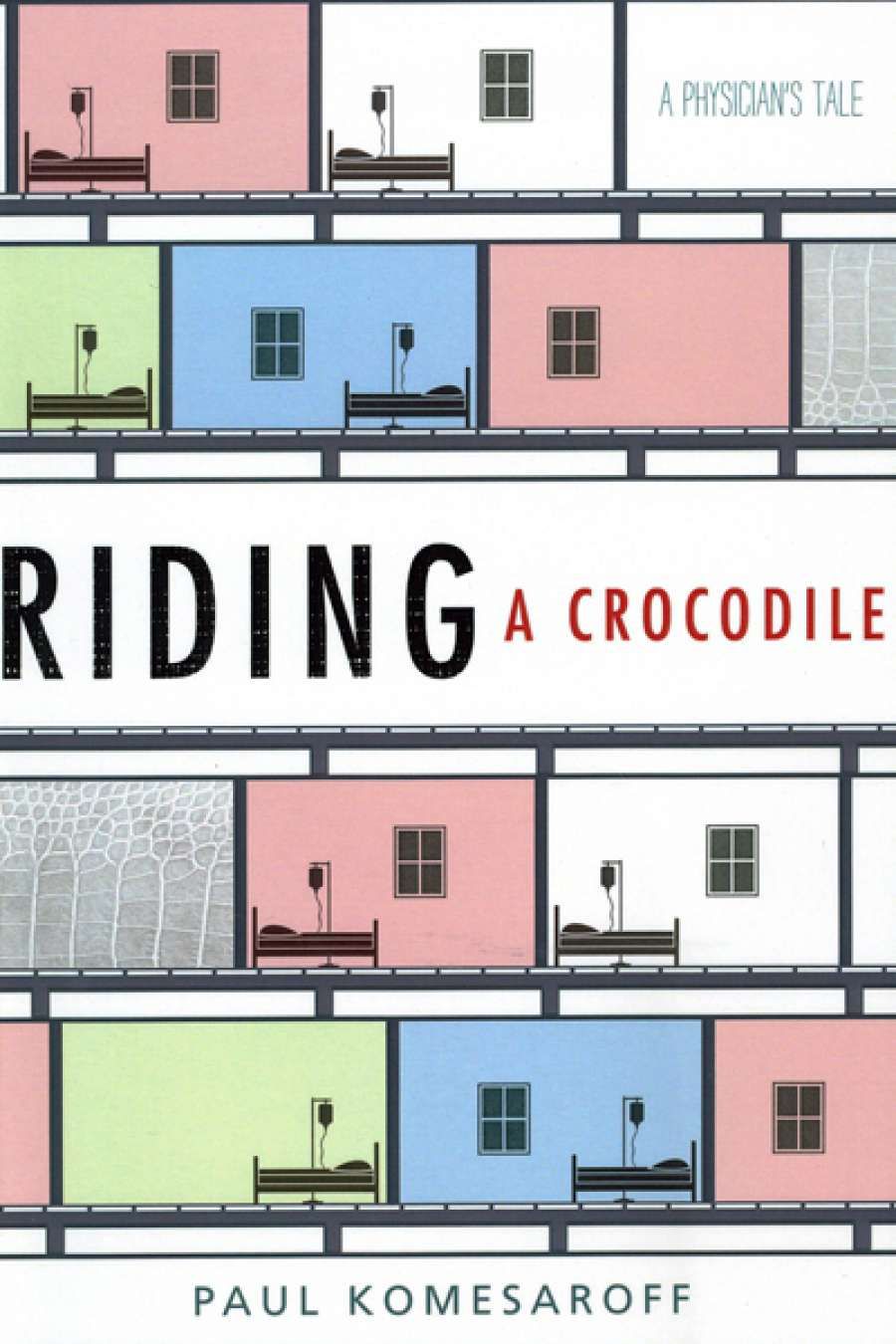

- Book 1 Title: Riding a Crocodile

- Book 1 Subtitle: A physician’s tale

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $26.99 pb, 357 pp

American doctor and writer Ethan Canin noted in the New York Times that ‘for a writer, medicine has the merit of constantly bringing you close to the dark side of life’. Like Canin, Komesaroff has worked in hospitals, and he draws on this darkness for both plot and theme. The novel’s protagonist is Professor Abraham Nevski, a caring, likeable doctor, though not without flaws. A series of unexpected deaths occur in the hospital, and Nevski starts to investigate. At the same time, he is mourning the death of his wife and fighting the growth of corporate managerialism at the hospital. While the book is more hospital story than detective story, there are some interesting twists in the mystery and aspects of the dénouement were surprising.

It is not plot, however, that gives this book its energy, but rather the themes it explores. I imagine that Komesaroff is fascinating to talk to, in particular about the issues his novel raises. At what point should we move from medical intervention to palliative care for patients over seventy? Who can make decisions about an individual’s quality of life? What role should family wishes play in decisions about medical care for very ill or disabled people? How should financial, medical, and ethical issues influence hospital decision-making? These and many other ethical questions are raised in this novel, both through the action and through Nevski’s inner monologue and discussions with colleagues. To explore these issues, Komesaroff goes further: he has Nevski write an article about ethics in medicine, extracts from which are included in several chapters of the novel. These sections, reproduced with modifications from Komesaroff’s Experiments in Love and Death (2008), are interesting meditations on the complexity of medical ethics in practice, but they do interrupt the flow of the novel.

Komesaroff uses detailed case histories of hospital patients in a similar way. Each one is fascinating, but the use of so many becomes overwhelming. There is a reason why novels, like soap operas and our own friendship circles, usually have between ten and thirty key players or characters. This seems to be the number of people and inter-relationships we can hold in our own minds. (Francis Spufford suggests this may be because we once lived in hunter–gatherer groups of this size.) In a novel with well over fifty characters, as here, the author is unable to develop the characters and the reader doesn’t care much about most of them. The characters seem to exist largely for illustrative purposes.

Paul Komesaroff (photograph courtesy of UWAP)

Paul Komesaroff (photograph courtesy of UWAP)

Of all the patients, I was particularly intrigued by Ursula Timoshenko, who sees Nevski regularly and pours out a litany of medical jargon about her ailments as if ‘words were, and remained, her life’. Although her conversation and seeming hypochondria are extreme, she is neither a caricature nor comedic figure but rather a figure of tragedy, caught in the mesh of her own grief and traumatic past. For me, she was one of the few characters beyond Nevski and the young registrar, Rebecca, who came to life. She illustrates nicely Nevski’s (and one suspects the author’s) belief that, ‘You don’t have to climb Mt Everest or swim the Amazon or go bungee jumping to experience the limits of experience … You don’t need to ride a crocodile. You just need to listen to the stories of people.’

Like the characters, the dialogue can be stilted and unconvincing, all too obviously serving the novel’s themes. There is repetition, as we are unnecessarily given Nevski’s inner monologue as commentary on the action. It is a strange conjunction: such sophisticated ideas in a novel that is rather unsophisticated in terms of writerly craft. The pen-and-ink illustrations and commonplace chapter headings (‘Late Night Phone Call’ or ‘Inner Tumult’) add to the amateur feel of the book. And yet, here we have an Australian novel of ideas, starting with a quote about the death of the other from philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. This is a novel that lays out the complexity of clinical practice in a way that makes it interesting and comprehensible to lay people. Komesaroff also mounts a convincing critique of how economic rationalism is imported into the health-care system and of simplistic approaches to rationing care and to euthanasia. Like a hospital, this novel is an odd mix of the intriguingly complex and the mundane.

Comments powered by CComment