- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Media

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The age of David Syme

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Syme made his name and his fortune in newspapers – specifically The Age – and his life’s course might be compared with the workings of a gigantic web offset press.

I have watched such machines at work. They start off slow; the rolls of naked newsprint snake by gently, round and round. When the presses roar to life the noise is astonishing; the paper is stretched like the thinnest of skins as it flashes, smooth and furious, through the machine, soaking up words and pictures. If the paper breaks, the whole thing unravels and the run must be reset. So it was with Syme, the brilliant but perplexing man who owned and ran The Age from 1860 until his death in 1908. At its peak in the 1880s, only the London dailies had higher circulations. One in ten people in Melbourne bought a copy.

- Book 1 Title: David Syme

- Book 1 Subtitle: Man of The Age

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 hb, 447 pp

The frenetic course of Syme’s life was interrupted several times by what biographer Elizabeth Morrison calls ‘a breakdown in health’. These snaps are perhaps even more interesting than the ordinary flow, because they humanise a man whose drive to know, breed, build, acquire, control, dictate, and copy check was otherwise unrelenting.

Syme has been the subject of two political biographies, in 1908 and 1965, but Morrison’s ambition is to reveal the many other sides of the radical liberal newspaper man’s life, notably his family, his farming (he bred livestock and grew fruit in the Yarra Valley, Riverina, and elsewhere), his property development (in 1906 his six-storey ‘Melbourne Mansions’ opened on Collins Street), and his writing. Syme was the author of four books on industrial science, representative government, science, and the soul.

Aside from an overview ‘prelude’ chapter and a suggestive ‘afterword’ – in which Morrison speculates that Syme exhibited some signs of paranoid personality disorder – the book is a chronological, meticulously researched if somewhat conventional scholarly account of a remarkable life.

Born in 1827 in North Berwick, Scotland, Syme was the youngest of seven children. His father, George, had trained as a minister but worked as a parish schoolmaster; he squabbled vigorously with the local Kirk. Unlike his three older brothers, Syme was not sent to university. Indeed, no provision was made for his future. George died when Syme was seventeen; after that, his brothers looked out for him.

At fourteen, David dreamed of being a sailor. He taught himself to navigate and to smoke. At eighteen, he was drawn to theology. By twenty, he wanted to become a linguist. He became proficient in Hebrew and started to learn Arabic, immersing himself in pre-Christian societies. Then, in 1847, he snapped. As Morrison observes: ‘Driving himself to study, overworked, he reached a point of nervous exhaustion and, most likely, deep depression.’ A spell in Europe followed, probably funded by his brothers. On his return to Scotland, Syme worked as a reader on one of Glasgow’s fourteen newspapers. Compared with studying ancient languages, the work was a doddle and Syme was pleased with his performance although journalists may have felt otherwise. A manager noted that his proofreading was ‘severe’.

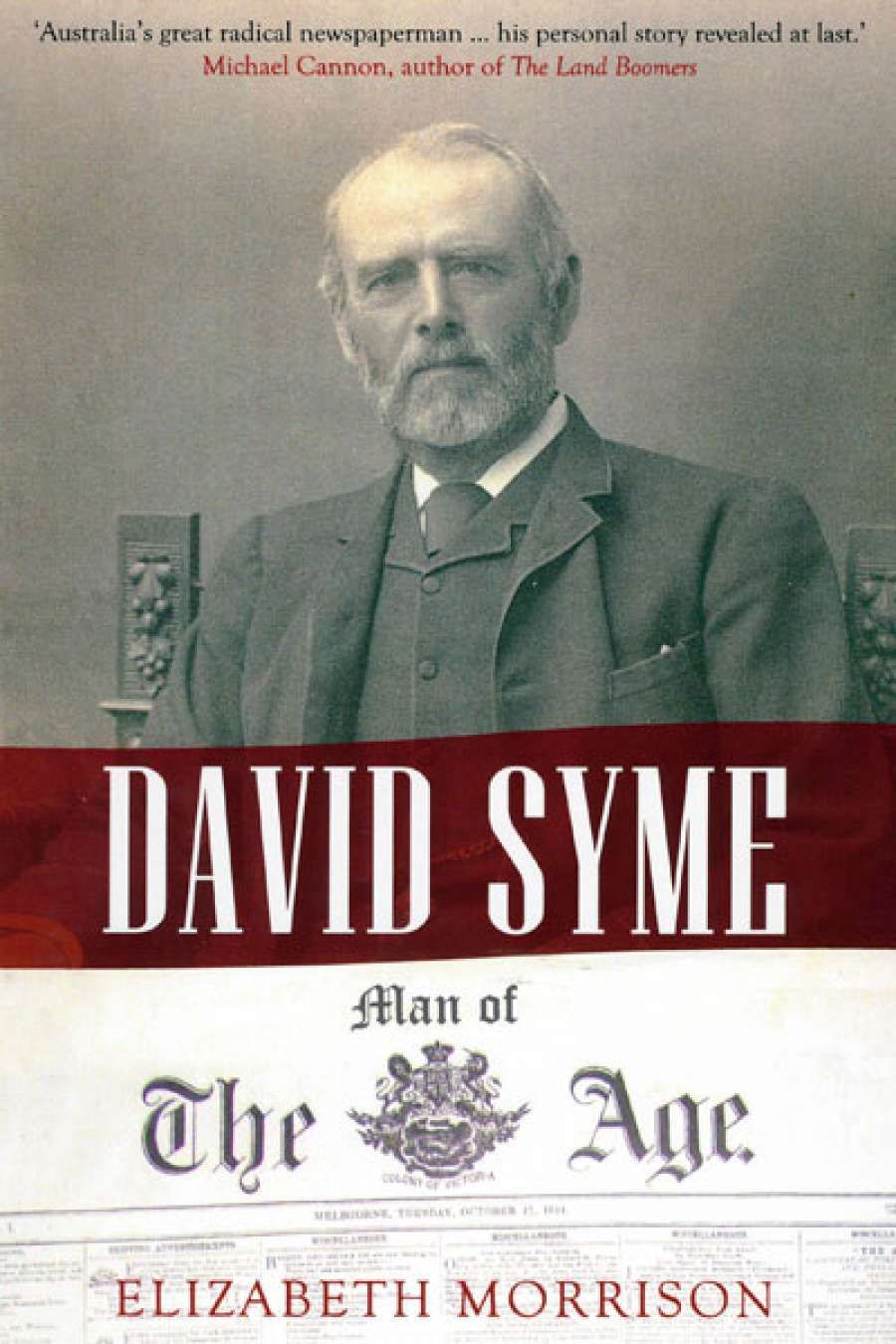

David Syme (detail from title cover)

David Syme (detail from title cover)

Syme arrived in Melbourne in 1852 (via the Californian goldfields) and walked to Castlemaine to begin looking for gold. He was robbed, but persisted for three years. ‘The lesson to me was never to be cock sure of anything,’ he would write later in his notebooks, a typically pessimistic assessment. Here, as elsewhere, Morrison has a reporter’s knack for selecting, from diverse primary-source material, the direct quote that best sums up a subject.

In 1856, Ebenezer Syme bought The Age, with financial help from his younger brother David. The former missionary turned journalist was a strange looking fellow: black hair combed across a high forehead; small wire-rimmed glasses; and a fluffy black beard that has the texture of fresh candy-floss. Morrison describes him as ‘foolhardy, impetuous and with no business sense’, quite the opposite of canny David. In September 1956 the two brothers became partners in The Age. Ebenezer was the editor and David wrote mining news for the Weekly Age, one of several periodicals the company put out. He also ran a successful road contracting business.

When Ebenezer died in 1860, David took over. His sister-in-law Jane was his new partner. For the next eighteen years, the newspaper business supported Syme’s growing family, as well as Jane and her five children. The widow had moved to London, and she dispensed frequent business advice from there. She emerges as a fascinating, duplicitous woman. Morrison rightly places Syme’s tortuous professional and personal relationship with her – and later with her son Joseph, who succeeded Jane as Syme’s partner – at the centre of this book.

Jane fooled Syme. She had left Melbourne already pregnant with the child of Robert Palk, a shyster who pretended to be a medical doctor, and she had four more children with him. The first two were illegitimate. Syme was crushed when he found out. He had felt duty-bound to support her and had clung on at The Age, a mediocre, barely solvent paper outsold then by The Argus and The Herald. Those first six years in charge brought on a second snapping point and in 1866 Syme had a nine-month holiday in Europe, a break from what he described as the ‘killing work’ of running a paper.

Victory rotary printing machines, introduced to Australia by Syme in 1872 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria, IAN10/06/78/104)

Victory rotary printing machines, introduced to Australia by Syme in 1872 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria, IAN10/06/78/104)

When he got back, Syme cut the cover price (twice), commissioned gossipy columns on business and science, bought rival morning paper The Herald and turned it into an afternoon one, imported and installed the first rotary press in Australasia – the English-made Victory – and began negotiating with other newspaper publishers to set up an Australian-owned cable news cooperative. He also introduced serial fiction to Australian newspapers. In 1872, The Age published the first part of To the Bitter End, a bestselling novel by English writer Mary Braddon. Personal columns, manufactured events (Baldwin Spencer’s anthropological expedition to the outback, which Syme financed, provided copy for a long-running series), serial fiction, illustrations, and well-turned gossip were central to the paper’s success. In business, technology and culture, Syme was dazzlingly sophisticated and shrewd. Would that there was such a person running media companies now.

None of this effort sat easily. In 1872, Syme was again unwell from overwork. ‘For a week at a stretch I never was in bed or undressed,’ he wrote to Jane. He was ‘wretchedly out of sorts’ and lashed out often. His communications with the manufacturers of the cutting-edge Victory presses were controlling, churlish, carping, critical, and alienating. This sort of unpleasant behaviour was common. Syme was tall, lean, rich, good-looking, and powerful, but he was also a pain in the neck. Morrison does not spare her ‘querulous’ subject. Indeed, the range of adjectives she employs to describe Syme’s outbursts is one of the delights of this book.

Yet we are also shown the kindness and vulnerability that existed ‘behind a formidable mask’. In 1877, Syme was in London – suing a newsprint supplier, among other things – and he wrote regularly to his wife, Annabella. He missed her and their seven children terribly. ‘I think dearest I have no more to say. I often think of you, & what a blank life would be without you.’ Here, the reader can sense a different kind of man, someone delicate, loving, and cultured, a man marked with the indelible ink of family and all the burdens and joy it can bring.

Comments powered by CComment