- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The making of a new Labor martyr

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gough Whitlam may not have been one of the Australian Labor Party’s greatest prime ministers, but, since his defenestration by Governor-General John Kerr in 1975, he has been embraced as one of the ALP’s great martyrs. Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government galvanised the Labor movement. To Labor eyes, Kerr was Pontius Pilate and Whitlam the slain Messiah. New followers – many of them, like Whitlam, university-educated progressives – joined the ALP. New ideas were aired through policy think-tanks such as the Labor Resource Centre, headed by Jenny Macklin, a future federal deputy leader. Out of that angst and rage, a new ALP was forged. Labor was no longer a troglodyte party ruled by factional warlords and sectarian hatreds. It was a modern progressive movement hell-bent on winning and wielding power. After all, as Whitlam famously said to an ALP State Conference in Melbourne in 1967, ‘Only the impotent are pure.’

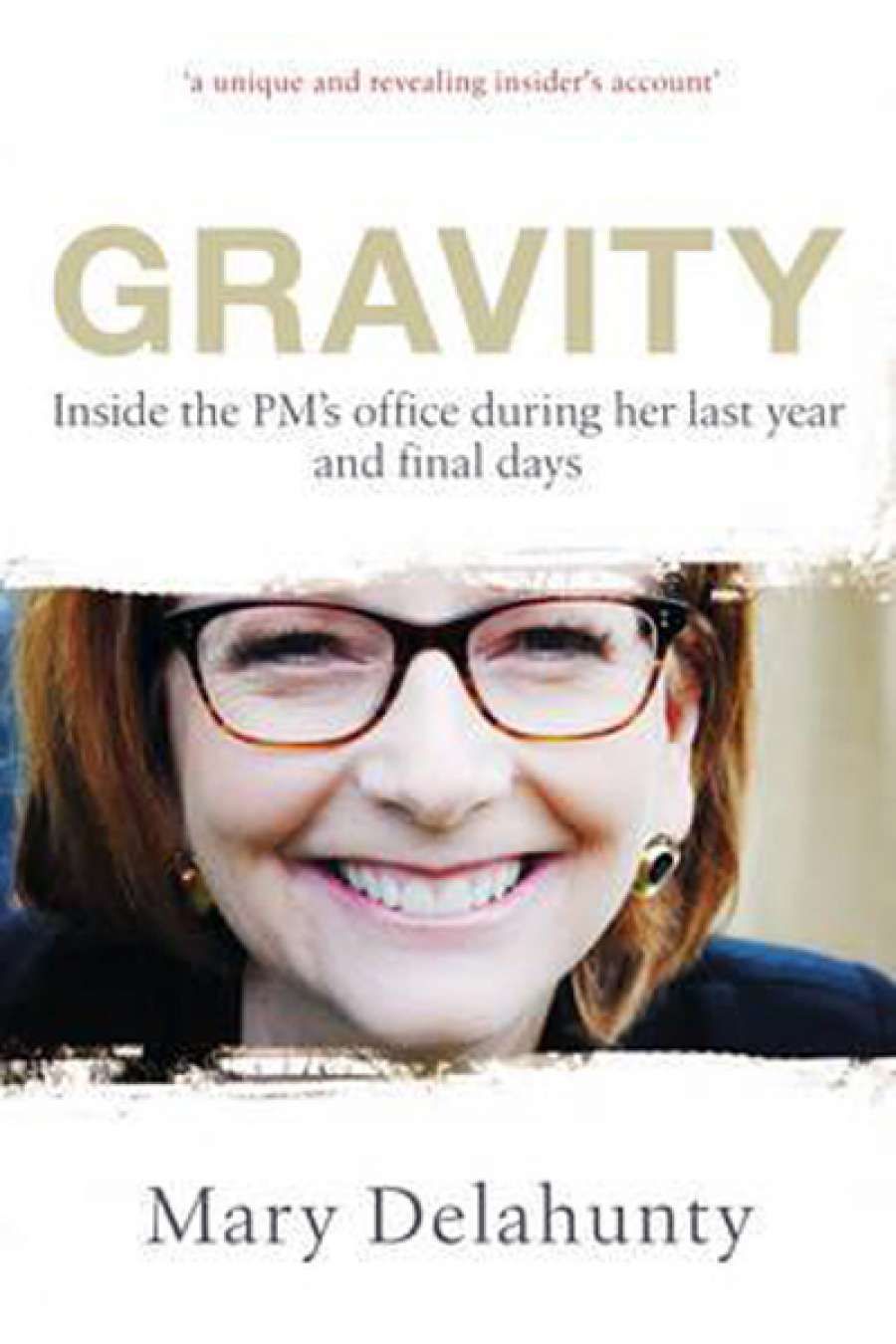

- Book 1 Title: Gravity

- Book 1 Subtitle: Inside the PM’s office during her last year and final days

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $29.95 pb, 270 pp

- Book 2 Title: Rudd, Gillard and Beyond

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin, $9.99 pb, 165 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): /images/September_2014/Rudd%20Gillard%20-%20colour.jpg

That’s why it is a mistake to think of Whitlam as Kerr’s victim or a romantic failure, because the man was a political battering ram – a revolution in a suit who constantly ‘crashed or crashed through’ in his fights to modernise the nation by first modernising the ALP. A progressive in excelsis who, with Don Dunstan, battled against the Party’s dogged adherence to the racist White Australia policy. ‘An Orpheus in a bogan underworld,’ according to Paul Clarke’s entertaining documentary, Whitlam: The Power and The Passion (2013).

Paradoxically, instead of finishing off Whitlam’s reform mission, his political crucifixion finished the job. After all, it is arguable that the reforms of the Hawke and Keating governments would not have happened without the bitter lessons of the Dismissal. Only time will tell whether similar conclusions can be drawn from the rise and fall of Julia Gillard.

Gillard wasn’t a bad prime minister. She was an efficient administrator and legislator, a masterful negotiator (as Tony Abbott learned during the seventeen-day stalemate that followed the 2010 federal election), and a powerful parliamentary performer (as Abbott discovered when he was on the receiving end of her now famous ‘misogyny speech’ in 2012). Of course, Gillard made mistakes as well, but it is too soon to decide whether she qualifies as an average, good, or great prime minister due to the long tail nature of government. We won’t, for instance, be able to gauge the success or failure of at least one Gillard initiative, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), for another decade.

This much is clear: like Whitlam, Gillard has been typecast as a martyr. Unlike Gough, though, Gillard is a martyr defined more by gender than politics. As one of her ministers, current Federal Labor Deputy Leader Tanya Plibersek, put it at the launch of one of a growing list of Gillard books, Mary Delahunty’s Gravity: ‘There was a gendered, pornographic, violent edge to much of the criticism of Julia that was beyond anything we’ve seen in public life in this country.’ During Gillard’s time in the Lodge, Plibersek said, her parliamentary colleagues debated the merits of responding directly to that vitriol, but decided to ignore the barbs:

We thought that we would be seen as self-indulgent, that we would be seen as defending our own personal positions … But as I think about it now, maybe that was a mistake; maybe if we’d been more methodical in calling out this crude behaviour more firmly from the start, perhaps we could have reined it in.There’s a bigger issue at stake than the attacks on one individual. To respond to these attacks is not only to defend one individual’s position, it is to fight for an idea of the kinds of roles women can play in society, it is to rebut the massive gendered abuse and its message to young women that it’s not worth the risk of putting your head up and getting involved in politics.

I was in the audience at Melbourne’s Sofitel Hotel as Plibersek spoke. The room was crammed with members of Emily’s List, a network dedicated to increasing the number of progressive women in Australia’s parliaments, including Victoria’s first female premier, Joan Kirner. I had been invited by Delahunty – a former state Labor politician I knew from my time as a political speechwriter – because, in 2013, my twelve-year-old daughter, Sophie, took the photograph of Gillard that appears on the front cover of Gravity.

I should explain how Sophie came to take Gillard’s portrait. Sophie, who has Down syndrome, was invited to a media event to mark the state of Victoria becoming a signatory to the NDIS. Sophie had been invited because my wife, Kirsten Deane, was deputy director of the Every Australian Counts campaign. Sophie had met Gillard at an Every Australian Counts campaign event a few days beforehand and had taken a shine to the prime minister. That’s not unusual for Sophie, who instinctively gravitates towards people who treat her normally – she has an internal radar for phoneys.

Julia Gillard (photograph by Sophie Deane, Museum of Australian Democracy Collection)

Julia Gillard (photograph by Sophie Deane, Museum of Australian Democracy Collection)

At the NDIS event, Sophie decided she liked the prime minister and, therefore, wanted to take her photograph. She borrowed my Nikon, walked up to Gillard and snapped four frames as the PM bent down to her eye level, then stood upright again – smiling all the while. Later that afternoon, I posted one of Sophie’s pictures on Twitter, and it went viral. Thousands of people responded to that picture. Why? Perhaps because it captures a private moment between a woman and a girl who had held her hand and sat on her knee, and, in doing so, reveals the person behind the politician.

At the Delahunty book launch, Plibersek started her speech by saying the photograph was her favourite portrait of Julia Gillard because ‘Sophie showed us something in Julia that was often missed … She is good natured, humorous and fun, as well as fiercely independent.’ Somehow, though, the good-natured and fiercely independent woman that Plibersek knows and that my daughter’s photograph shows was never able to connect with the Australian people.

In Gravity, Delahunty – who was a Walkley Award-winning television journalist before she jumped the fence to become a politician and minister in the Bracks government – sets out to understand what went wrong. She loiters with intent around Gillard’s private ministerial office for the best part of a year. She watches events unfold from the inside; interviews the prime minister, her advisers, and friends; buttonholes press gallery stalwarts such as Michelle Grattan, Tony Wright, and Laura Tingle; and, in the final hours of Gillard’s leadership, even accosts Bill Shorten in a stairwell to implore him to keep supporting Australia’s first female prime minister.

For Delahunty is not just an observer – she is a participant as well. She sees the flaws of the Gillard government, such as a tendency to push out half-baked policies and an inability to explain itself to the Australian people in short, sharp sentences. As Delahunty says:

A winning political trifecta is built on purpose, policy and PR. In the year I closely observed Prime Minister Julia Gillard she spoke often about purpose in politics: why she was there; and policy, what she was doing … But effective public relations was denied her.

The ways in which Gillard was denied a fair public hearing was ably catalogued by Anne Summer’s excoriating The Misogyny Factor (2013). In Gravity – as in her memoir, Public Life, Private Grief (2010) – Delahunty is guided by the feminist maxim that the personal is political. She is also fascinated by Gillard’s ability to keep going in the face of what Plibersek correctly diagnosed as ‘gendered, pornographic, violent’ criticism. At one point, Delahunty says, ‘love her or loathe her, this prime minister was a portrait of resilience’. That is what Gravity is – a contemporary snapshot of the most polarising prime minister since Malcolm Fraser.

Reading more like an extended Quarterly Essay than a book, Gravity is an important time capsule. It captures the comings and goings, one-liners and backhanders of many of the people who had a part in the making of Gillard’s martyrdom before they could rewrite history.

One of the voices missing from Gravity is that of Kevin Rudd, but he has plenty to say in Troy Bramston’s intriguing booklet, Rudd, Gillard and Beyond. Bramston – a former Rudd staffer turned News Limited journalist – doesn’t speak to Gillard, but has one-on-one interviews with numerous players, including Rudd, and it is Rudd’s view of the world that percolates through Bramston’s pages.

Kevin Rudd (right) and Julia Gillard (left) at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006.

Kevin Rudd (right) and Julia Gillard (left) at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006.

According to Bramston, Rudd saw his 2010 defeat by Gillard in almost Old Testament terms – as the ‘original sin’ that had to be atoned for. Rudd tells Bramston that he was too much of a ‘trusting bastard’, but claims he is not bitter. Given the way in which Rudd’s supporters sabotaged the 2010 federal election campaign – thereby making it impossible for Gillard to govern in her own right – that claim is difficult to believe.

Bramston says Rudd was a ‘malevolent force eating away at the integrity’ of the Gillard government. He also claims that Rudd’s brief return to the top job in 2013 ‘was undoubtedly the greatest comeback in Australian political history’. It is an interesting thesis, but I can’t agree. Rudd’s intifada against Gillard was nothing more than a political suicide bombing. It destroyed the legacy of one government (Rudd’s) and the possibilities of another (Gillard’s). Rudd may have made Gillard pay for the ‘original sin’ by taking back the big chair in Cabinet, but, in doing so, he made it possible for an Opposition Leader as divisive as Tony Abbott to canter into office.

The bitter lessons of the Whitlam years have been forgotten.

Comments powered by CComment