- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dark activities

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Mark Henshaw’s début, Out of the Line of Fire, appeared in 1988, it was, as literary editor Stephen Romei states in his introduction to the recent Text Classics reissue, the ‘literary sensation of the year’. A novel about an Australian author’s difficulties in writing about his fugitive subject, the young German philosopher Wolfi, it was very much a book of its moment, when a joyous postmodernism gripped Australian letters. In 1984 the country had hosted its first conference on the topic, with Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio, the rock stars of French theory; and by 1988 any serious young insect – myself included – was reading Jorge Luis Borges’s labyrinthine stories, Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Italo Calvino’s experimental novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. That same year Helen Daniel would publish her dense but hugely influential Liars, celebrating our novelists as purveyors of an Australian history (borrowing Mark Twain’s term) made up of ‘beautiful lies’. Henshaw’s novel also carries something of the crackling energy of our bicentenary when our literature was shedding a realism associated with colonialism while announcing a stake in international (often, but not always, European) intellectual traditions.

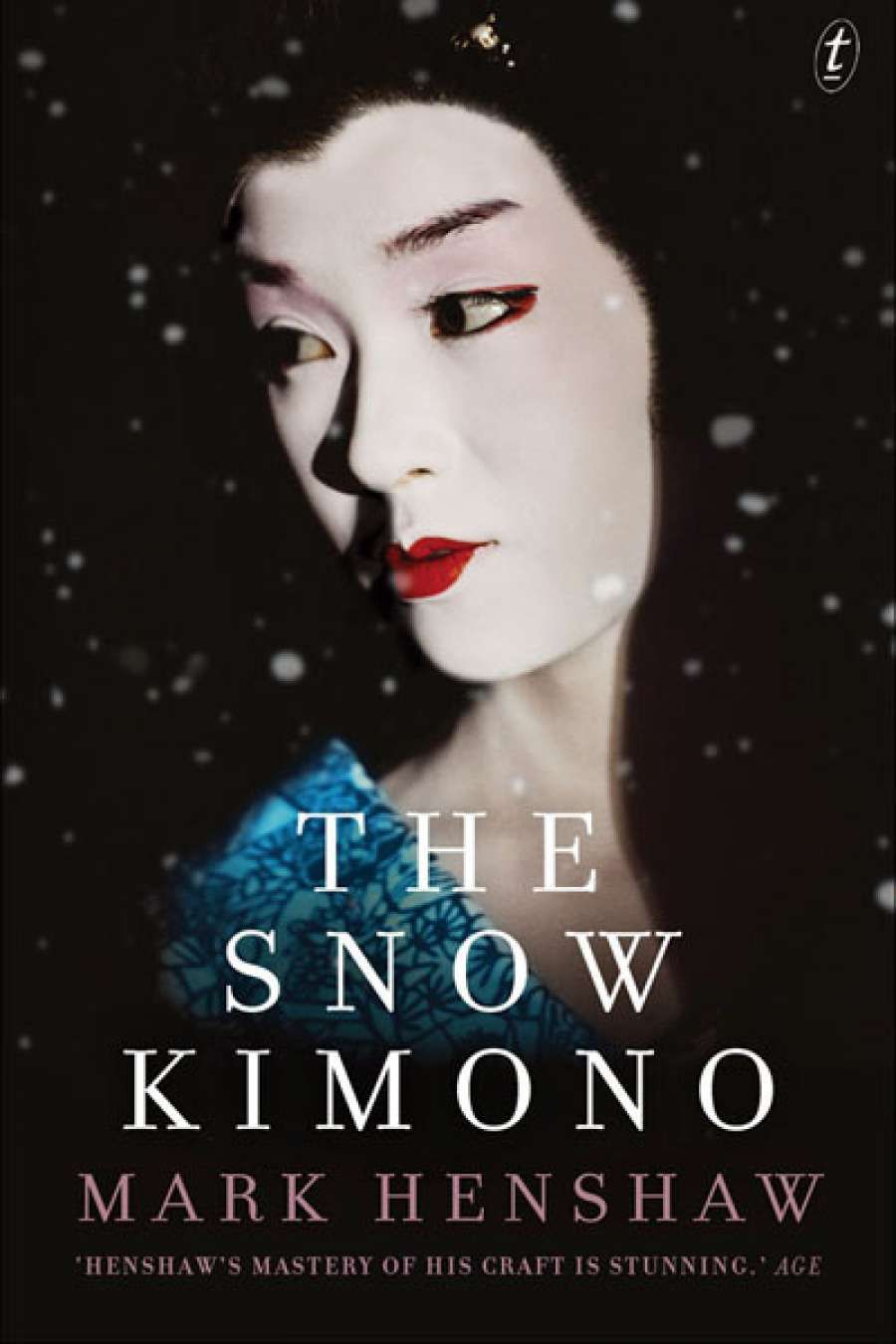

- Book 1 Title: The Snow Kimono

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 396 pp

Out of the Line of Fire was one of the first of a distinct strain of high-concept Austro–European experimental hybrids like Brian Castro’s Double-Wolf (1991), in which Freud’s ‘Wolf Man’ haunts the Blue Mountains, and John A. Scott’s Paris-based What I Have Written (1994). There was no doubting the novel’s ambitions to stand up in a transnational literary context. Its opening paragraph was a conversation with Calvino’s smart, elusive, fragmentary work, cleverly parsing the very difficulties of writing a beginning; and it went on, through the documentary evidence Wolfi supplied about himself (including extracts from his PhD-in-progress about representation) and a selection of examples from the European high-literary canon, to meditate on the challenges of drawing a line between fiction and non-fiction.

Whether such intertextual gymnastics stand the test of time, now that their novelty is past, is a moot question. For this reader, I would say, only partly, though it is nice to return to a moment in which books were celebrated as dynamic, sexy, physical objects. Even back then not all reviewers were enamoured of the sexual politics of the novel, in which women, via porn, rape, kidnap, peeping, and incest, seemed to always be at the pointy end of its jouissance. One does see, looking back, a regrettable tendency for our younger male experimental novelists to see Europe as a Playboy Mansion of the mind (which would make Kundera its Hugh Hefner). Nevertheless, it is fascinating, reading Henshaw’s novel again, to think about how far, in our current celebration of ‘storytelling’, we have moved toward a notion of stories as embodying truth, rather than as glittering, unstable matter.

The Snow Kimono is Mark Henshaw’s second novel. Alhough it comes after a twenty-six year gap, the impact of the first book means that there is a certain buzz around this publication. Fans will find Henshaw’s preoccupations have remained remarkably consistent. Set in Paris, and winding through Algeria and Japan, this is also a story about the difficulties of understanding another person’s life: in this instance, the mysterious author Katsuo Ikeda, a poor boy sponsored through school by an unknown benefactor, whose smouldering resentment has manifested in acts of increasing psychopathy.

This time, however, there are two men on the case. The novel opens in 1989, in Paris. August Jovert, a retired inspector of police, returns from hospital after a minor traffic accident to find an elderly Japanese man, resembling Emperor Hirohito, waiting outside his flat. (Jovert’s name is surely intended to recall Javert, that unbending and obsessive agent of the law in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.) Tadashi Omura, former professor of law at the Imperial University of Japan, begins in his ‘strangely mesmerizing voice’ to tell a terrible story from his Japanese past. It connects to one of many Omura will tell about his school friend Katsuo, whose dark activities have continued to intrude into the conservative life Omura has made for himself.

Omura and Jovert have family guilt and lost daughters in common; and Jovert’s Algerian activities still trouble him. But it is the Japanese stories that dominate, with many plot elements borrowed from Japanese literature’s interest in revenge, psychopathy, fetishism, and paid erotic enslavement. To these Henshaw adds a distinctly Western, Freudian layer, evident in the novel’s primal scene connected to a beautiful kimono that a young girl is destined to wear when she enters Katsuo’s warped world. As the dyes set in the snow, the girl watches horses fucking bloodily, the stallion’s penis like an ‘arm’, and sustains an injury herself that will become significant in the novel’s twisted family dynamics.

As the stories accumulate, the novel questions authorship and the slipperiness of memory. Yet – perhaps because Henshaw appears to have been reworking this book since at least 1994 – the sprightliness of its predecessor is lacking, replaced by an oddly affectless, flat prose. The effect is like watching the kind of arthouse film in which everything receives lingering attention from the camera – the rain on a window pane, light on a flagstone park – and especially women’s sufferings, as a highly aestheticised element of the mise en scène. The body count of small children is also troublingly high. While the narrative twists are challengingly clever, and there are perhaps legions of fans who will still see only the textual playfulness, I finished The Snow Kimono with a queasy sense of discomfort, and not, I sense, of the sort intended.

Comments powered by CComment