- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Orchestrating the gaps

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It may seem strange to begin a review of Paul Carter’s extraordinary poetry collection by quoting the words of another writer, but these lines of Boris Pasternak’s – taken from his essay in The Poet’s Work (1989), a collection of writings by twentieth-century poets on their art – seem particularly pertinent:

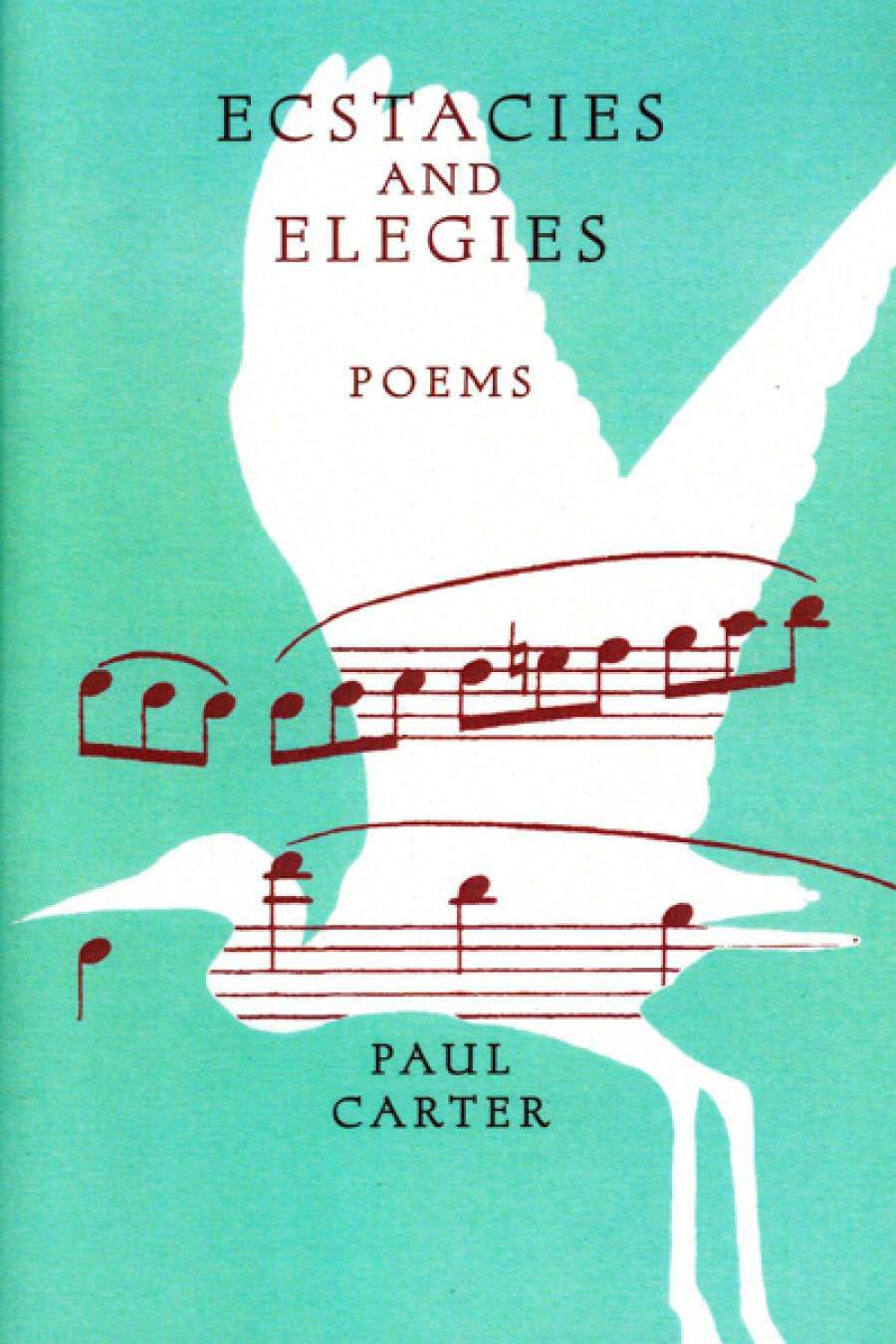

- Book 1 Title: Ecstacies and Elegies

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $24.99 pb, 188 pp

With this comment, Pasternak attempts to differentiate the inherent qualities of poetry from prose. His insight serves as an appropriate perspective from which to appreciate the poetry of Ecstacies and Elegies. Carter’s title itself portends the tumult of the pages that follow and a dictionary is indeed a handy companion for a journey that weaves through intellectual sites as varied as an improvisation on quinces; a meditation on the bees and honey of culture; a poetic lecture on the significance of public space (delivered in Warsaw by the poet, who is also a renowned public space architect and critic); a pilgrimage tour of Spain; an imagined poetic biography of Scarlatti; and, finally, a sequence of thirty-nine poems in which Carter interrogates the emotional and intellectual landscapes of a broken relationship.

Metaphorical improvisation is a favoured trope. In the opening poem, ‘New Quinces’, which bears a dedication to Australian poet–librarian Barrett Reid, the quince, by turn, is ‘obdurate’, ‘animalesque’, and an ‘Eden out of reach’. The quince as metaphor invokes a kind of sovereign representation of the ‘singular’ in creativity, and stands as a tart protest against (or perhaps for) death and its accompanying existential anxieties. The use of metaphor in Carter’s hands is dizzyingly kaleidoscopic and boldly counteracts the common dictum that poets should avoid ‘mixing their metaphors’. As Terry Eagleton has said in How to Read a Poem (2007), ‘Poets, then, are the materialists of language’ (so emphasising the complex dance between syntactical complexity, on the one hand, and plainness and transparency on the other).

Paul Carter

Paul Carter

Carter’s poetry is erudite, often opaquely so, and sometimes gravitates towards the cliff edge of intellectual interiority, but the vigour of the language and its rather canny evocation of the spaces between individuals, between memories, between speaker and listener, between history and present, between reality and imagination, work to create a remarkable creative tableau of poems that inhabit a deliciously ambiguous psychology. Sometimes it is not clear who is being addressed in the poems, but the elegant confidence of the speaker creates intriguing aphorisms, such as: ‘I am trying to see it all at once: the strings that orchestrate the gaps ...’ (‘Scarlatti in Lisbon’); or, ‘Language is not your own, you find a space in it’ (‘A Lecture in Warsaw’).

The latter poem is an important one. In it, Carter highlights his sense of space as form but also his sense of the present as a fragile surface that can be scratched and broken, exposing a kind of verticality of time such that history becomes a spatial excavation in which present and past are in contemporaneous dialogue: ‘If a surface were there that could be scratched, / but all the way down fossils lie with bottle tops; / wasp-hipped figurines have settled with the trash.’ And still later in the same poem:

How do surfaces touch? What is the politics

of pressure? People group like molecules,

or spread dust in their ordinary motions.

A between space is where it happens, a place

of surfaces, where tracks in flight come upon

one another, and pause, about to speak.

To depict it demands a measure of nearness,

where nothing is drawn unless drawn to another.

Of interest, many poems are created with formal attention to line and stanzaic rigour, while others meander, creating long sequences of flâneur-like ideas and observations, usually with the self as an active participant at the centre.

The first poem in the collection rhymes formally, but rhyming couplets appear inconsistently in later poems, and slant rhyme and strong alliteration can be found. These techniques, together with a sure melodious ear, offset some of the more abstract or symbolic tendencies. It can be rewarding to encounter strong sensual, visual images such as those that appear in ‘The Castle’ (Part 10 of ‘Scarlatti in Lisbon’):

Sending the servants ahead to prepare our rooms,

we lie for an hour under makeshift pavilions:

late summer and from the edge of the cork grove

the reaped fields shimmer with Moorish tents.

A cricket at his sewing machine close to my ear;

a pipit calling, scraps of conversation lifting

from the fête champêtre, syllables light-dark,

and from the ditch the muleteers’ low sotto voce.

Sometimes I can make out the line that joins

the notes of nature into a theme of sorts;

out of the chaff of summer’s great harmony

I can winnow phrases I was proud to perform.

But mainly I dream of painted ceilings where

the behaviour of clouds is guaranteed

and the tedium vitae is redeemed

with amorous interludes between shepherds.

A man was hanged where we set out today,

his departure delayed because of ours;

like a scarecrow protecting the public good;

loyal subjects paved the road with flowers.

On the road to the monarch’s bower of bliss,

I conceive the genealogy of culture is this:

blood into petals and from the scatter of heads

cadences turning the howl into music.

In this poem and in others (for example, ‘Starlings at Aranjuez’, ‘The Relation’, ‘The Prayer’, ‘Soul Searching’, ‘Place Holders’, and ‘Pregnancy’) Carter achieves that particular frisson of language under pressure – that sensory evocation and melodious improvisation that characterise superb poetry.

Ecstacies and Elegies is a collection of august luminosity. These are poems to converse with. The reader is enlivened to critique, to explore ideas, to climb the metaphorical ladders that lead to no fixed conclusions, and to contemplate those exceptional moments of brutal candour and fraught purity that appear in the final sequence of poems (‘Night and Day: A Diary of Separation’). This is a remarkable and virtuoso collection, a creative adventure in words from a contemporary polymath.

Comments powered by CComment