- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Japan

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Turning Japanese

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Hamish McDonald has for more than thirty years written about foreign affairs and defence in Asia for publications such as the Sydney Morning Herald, Far Eastern Economic Review, and, more recently, as the world editor for the Saturday Paper. His writings on Indonesian politics and Australian complacency over the Balibo controversy have been more likely to put him in the firing line than on the bestseller’s list in Jakarta’s bookshops, but his tenacity and journalistic skills place him among Australia’s finest. In a departure from his usual subject matter, McDonald has shone a spotlight on Japan’s historical past in the form of a memoir. A War of Words owes its origins to a chance encounter while he was on assignment in Tokyo when the Japanese economic bubble was at its peak. After a fellow journalist gave him a box of papers that included photographs and an anecdotal manuscript of the life and adventures of one Charles Bavier, McDonald spent the better part of three decades piecing together the details of Bavier’s colourful life. Besides being an excellent tale, The War of Words represents an enlightening chapter in the history of both Japan and its ever-changing relationship with Australia.

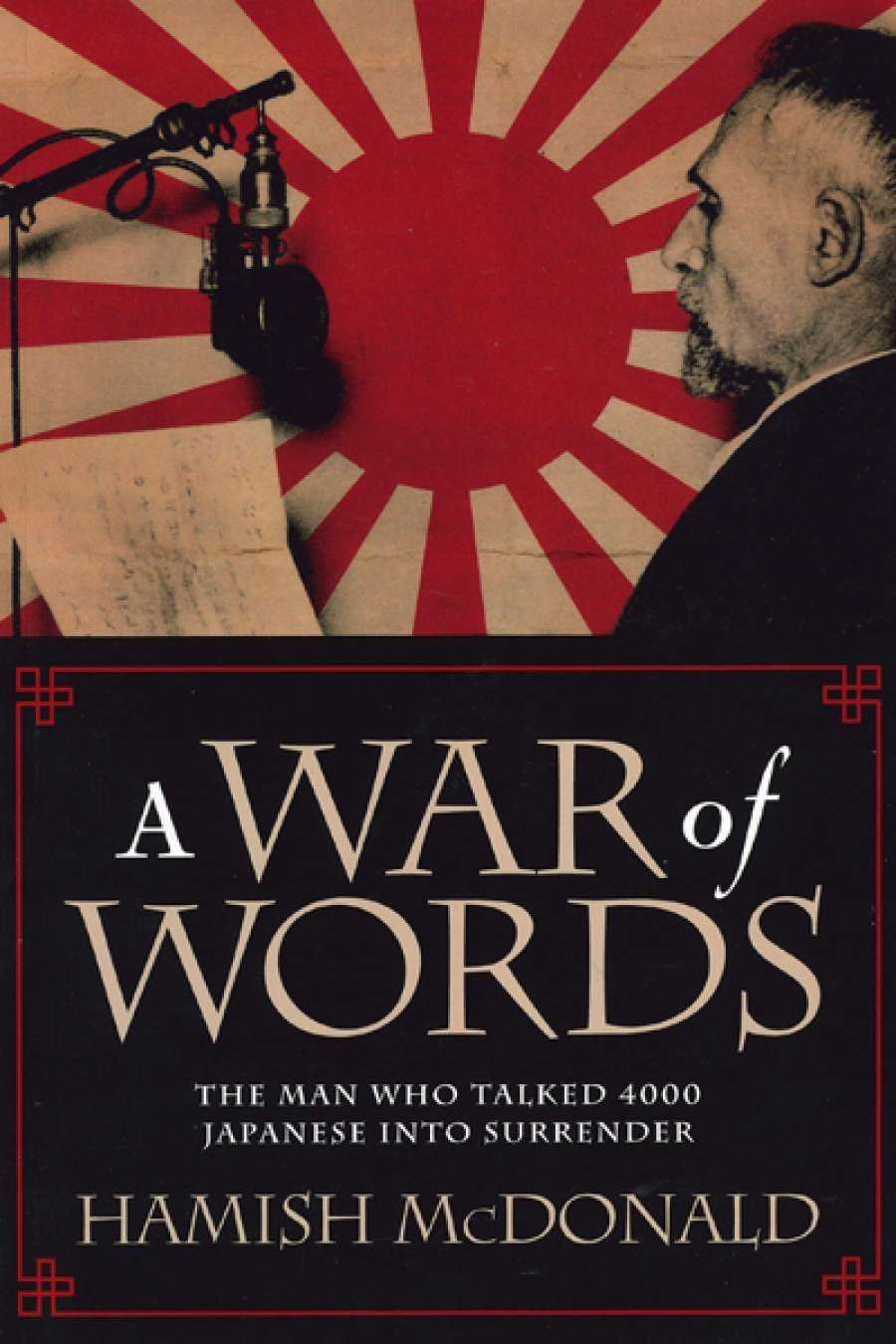

- Book 1 Title: A War of Words

- Book 1 Subtitle: The man who talked 4000 Japanese into surrender

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press $32.95 pb, 332 pp

John Bavier signed up for the Australian army when he turned 18

John Bavier signed up for the Australian army when he turned 18

Bavier’s life story is an absolute gift for a writer. The gut-wrenching scenario of an orphan abandoned in a strange land; the quest for military adventures in China and Turkey; tales of unrequited love; rejection in Australia and acceptance in Japan: it almost feels like a story James Clavell didn’t have time to write. However, Bavier’s was a life that existed somewhere between bad luck and circumstance, full of almosts and missed chances – but an eventful one all the same. Unable to find a niche for himself at home or abroad, Bavier was a conflicted individual caught between East and West. McDonald acknowledges that Bavier left some of his adventures undocumented, in particular those relating to his military assignments with MI5. However, he self-consciously fills the gap with his own speculative musings of what Bavier might have got up to during those obscure years. While other writers might flounder in this aspect, McDonald’s sound grasp of the history and politics of the region gives the tale the narrative flow that was no doubt missing in Bavier’s original manuscript.

McDonald’s book tells us much about Japan, especially by questioning what constitutes Japanese identity. Viewed from afar, Japan and the Japanese are often viewed as a single homogenous entity, a notion that the Japanese themselves often contribute to by referring to themselves as ‘we Japanese’. Bavier was in many ways the antithesis of the Nihonjinron, the collective theories of ‘Japaneseness’ that came to fruition in the late eighteenth century, only to be rekindled in the early years of defeat after the Pacific War. Popularised by a collection of more than 700 titles published by the Nomura Research Institute between 1945 and 1978, the now debunked corpus was a discourse that sought to demonstrate the quintessentially unique or innate characteristics of Japan’s cultural identity, and ultimately its difference from the rest of the world.

Odyssey’s end: Charles Bavier in Kyoto

Odyssey’s end: Charles Bavier in Kyoto

Halfu is a term often used for children of mixed parentage in Japan, and even in the early Meiji era, when Japan had finally been persuaded to open its doors to the West once more, mixed-race children were a far from common occurrence. Seen as somehow bridging East and West, they are quite distinct from gaijin, a rather crude abbreviation of the more formal gaikokujin used to refer to all non-Japanese in general. Bavier was an exception; effectively, he was neither half-Japanese nor a foreigner. The illegitimate son of a wealthy Swiss merchant and an unknown Western woman, he was abandoned by his father and raised as a Japanese by his father’s former mistress. Adoption was quite common during the late nineteenth century in Japan, but adopting a non-Japanese was virtually unheard-of in a famously insular country. Charles must have seemed an oddity to many of his classmates, yet they rarely mentioned his race, and never in a negative way. The general impression that emerges is that Bavier appears to have had a fairly straightforward upbringing in a country that was relishing its role as the new Eastern power among the family of nations. McDonald shows how, during Bavier’s formative years – and even much later – Japan was very much an outward-looking country, far more open to the idea of multiculturalism than it is commonly given credit for.

Japan is often remembered for the pseudo-fascist government that led the country into what is known as the ‘dark valley’. A War of Words reminds us, in a welcome way, that there was considerable interest in radical socialism at a grassroots level, which resonated through every levelof race and class in Japan. The existence of this subculture, and Bavier’s involvement in it, ran parallel to acts such as the ‘Peace Preservation Law’, which did much to snuff it out. One is left wondering what kind of country Japan might have been had events taken a different course.

Comments powered by CComment