- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cultural resonances

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The three parts of Dominique Wilson’s story are linked together by racial prejudice, of Australians towards Asians, and of Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese towards Westerners. She picks up this well-worn thread in pre-Federation Australia and weaves it in and out of the narrative, tying it off when China is in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. During the twentieth century, her three men – two Chinese and one Australian – are afflicted by racism to different degrees. How strange, then, to call her book The Yellow Papers, without explaining the significance of that loaded adjective. What papers? Wartime telegrams, ancient documents, or something else?

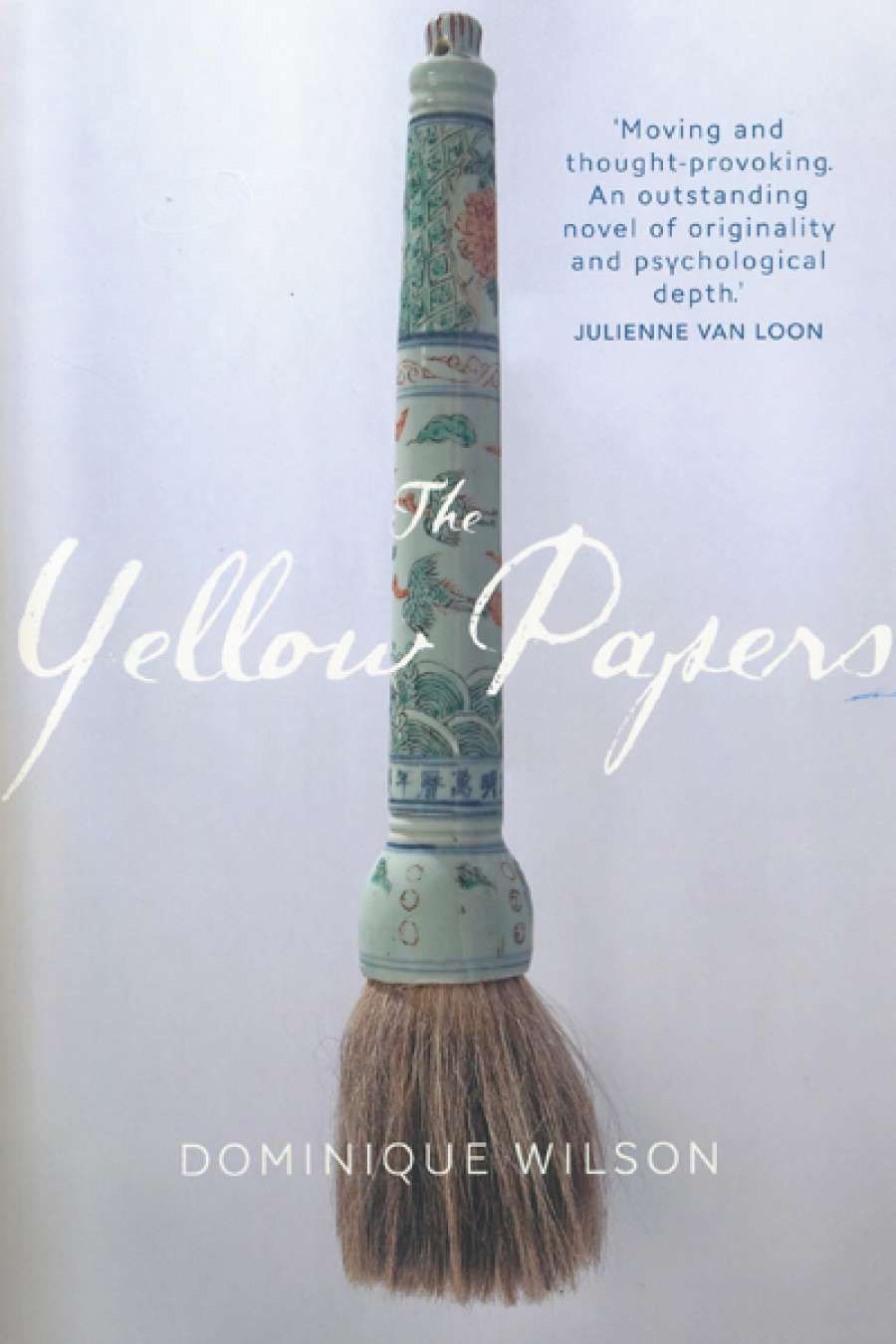

- Book 1 Title: The Yellow Papers

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.95 pb, 348 pp

As a boy, Chen is sent from China in 1872 to learn from the barbarians in the United States, is discriminated against, falls foul of the law, and ends up in Australia, where he indulges his love of botany as a gardener on a pastoral property. His story has resonances with Castro’s Birds of Passage (1983), in which the dual protagonists Lo Yun Shan and Seamus O’Young also reflect on the irony that when one goes to live among barbarians, one becomes the barbarian. Wilson’s three men, like Castro’s two, are at home in no country, yet this causes them nothing like the existential anguish suffered by Shan and Seamus. Chen survives in Australia, preserving two lifelong treasures, a copy of Tom Sawyer from his American host and a jade brush-rest given to him by his Chinese schoolteacher. He marries an Indian housemaid; they are childless, and his wife dies young; but apart from his lifelong guilt over not having returned to China for his mother’s funeral, Chen is presented more as one of Rolls’s pragmatic sojourners than Castro’s tormented outcasts.

The second of Wilson’s men is Edward, son of the pastoralist, in whom Chen awakens an interest in Chinese culture, which he goes on to develop as a linguist and art collector. As China passes through revolution, invasion by Japan, war, and another revolution in 1949, to war in Korea, Edward – as one of the few available Chinese speakers – is sent on successive official missions to Burma, Shanghai, and Korea to organise resistance ‘behind enemy lines’. With so much time and territory to cover, the account that Wilson provides of these dramatic experiences is rather spare. Edward’s story soon merges with that of Ming Li, the beautiful wife of a Shanghai businessman, and progresses from Australia through Asia and back, driven by how and where the secret lovers are to be reunited. Captured and tortured in Korea, Edward − who has done his own share of killing − returns to Australia. Now, we read, he hates anyone with ‘an Asian face’. Hardly an appealing character, Edward is ecstatically reunited with Ming Li in Hong Kong (despite her Asian face). Again, as with Chen’s courtship and marriage, their lovemaking is described in almost pulp-fiction style, and physical realism overpowers emotional empathy.

Ming Li, who is entrepreneurial as well as beautiful, contrives an exit from China for her orphaned thirteen-year-old grandson, Huang Ho (Yellow River), first to Hong Kong and then to university in Adelaide. He turns out to be the most interesting and complex of Wilson’s three men, determined to ‘build the country’ that, under Mao, has killed his parents. He refuses to speak Mandarin, complains that Hong Kong people are greedy, selfish individualists, has no respect for his lecturers and deliberately fails at university. Regarding the Australians’ pursuit of personal happiness as decadent, he fumes at the shortcomings of capitalism and a bourgeois education system that favours the élite. Soon, the sexual ingénue Huang Ho is in trouble with a girl, is sent to jail, and then to psychiatric hospital (where he and others are addressed as ‘gentlemen’). Eventually, back in Hong Kong, he calls his grandmother a filthy capitalist whore and smashes the precious jade brush-rest that has passed from Chen to Edward to Ming Li, a fragile talisman of cross-cultural communication. Worse follows, leading this complex tale to its climactic ending.

I cavil at half a dozen typos (including Chiang Kia-shek [sic]), and to the end I remain puzzled about the ‘yellow papers’. Does the title imply that the funerary papers that Chen failed to burn for his mother’s soul mysteriously affect all four life stories? If so, Wilson, though praised for her ‘unforgiving realism’, fails to make it clear. Compressing her research on a century of Australian–Chinese interactions into a historical romance novel reduces the reader-appeal she can generate for her characters. But it can be done, as Linda Jaivin’s two most recent novels show.

Comments powered by CComment