- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Woman in gloves

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For anyone who has ever complained about a difficult mother, or written a memoir about one, this is a humbling book. How trivial, by comparison, our complaints seem. The subtitle promises (or threatens) a disturbing memoir, and so it is. I found it difficult to get out of my head days after reading it.

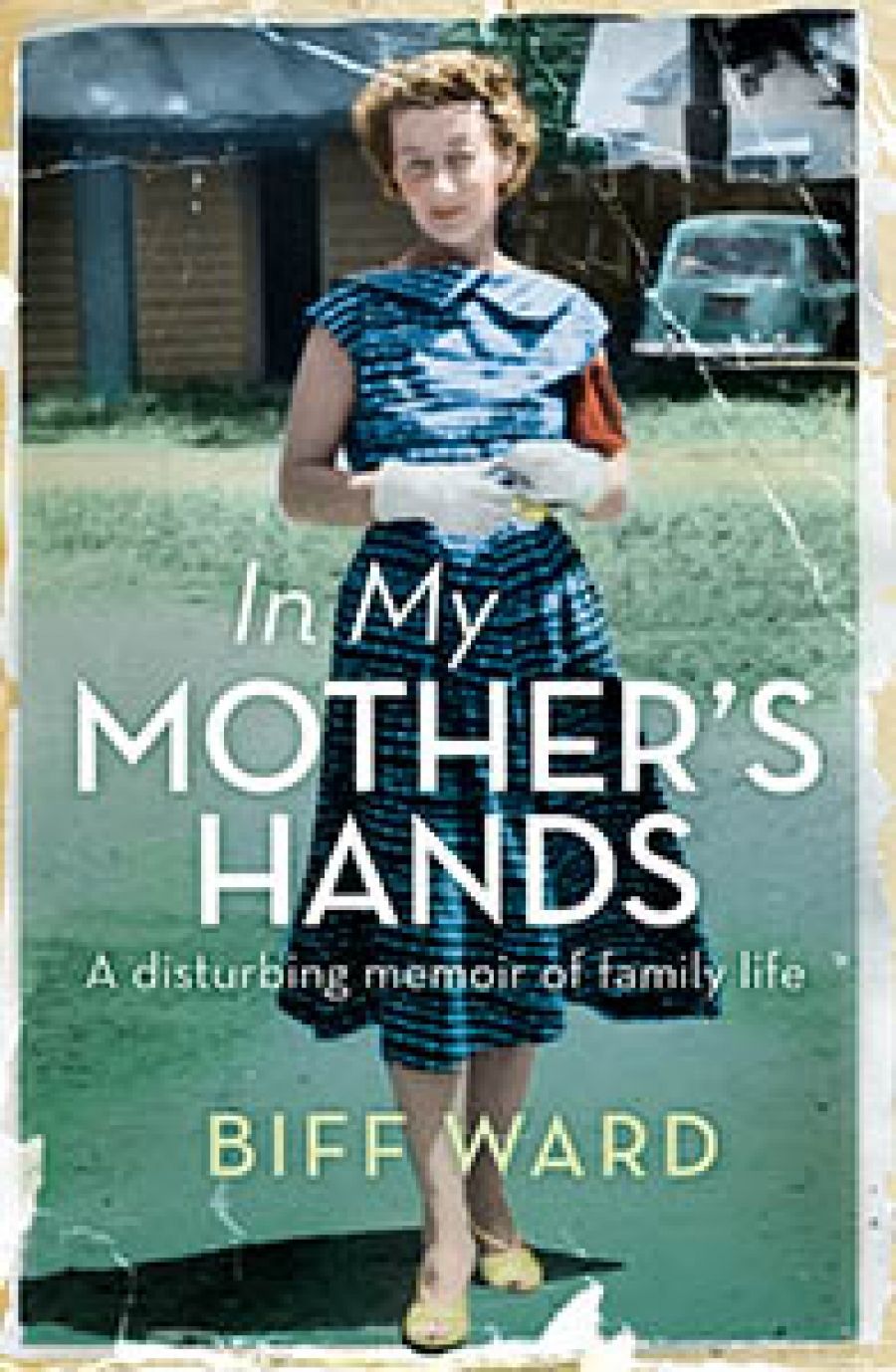

- Book 1 Title: In My Mother's Hands

- Book 1 Subtitle: A disturbing memoir of family life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 280 pp

Margaret was a beautiful woman, as the 1946 portrait by Paddy Taylor reproduced (unfortunately in black and white) makes clear. Her eyes are looking off sideways into the distance, as they usually did. The reticence and withdrawal became more pronounced as Biff and her young brother grew older. Russel was the rock in the family, the children’s carer, even the cook, not to mention the lively, gregarious parent who made things fun and had lots of friends. Margaret was off in her own world, sitting silently at the kitchen table with her cup of coffee and cigarette.

Biff, Russel, and Margaret Ward

Biff, Russel, and Margaret Ward

There were breakdowns, violent episodes, suicide attempts, brief hospitalisations. Margaret’s paranoid streak emerged; no doubt encouraged by the fact that Russel had joined the Communist Party and was indeed under ASIO surveillance. She became hostile to Russel and told him she had always hated him. He stuck it out, evidently feeling that he couldn’t commit her to an institution where the only treatment available was electro-shock therapy or lobotomy. At home, even when visitors were present, he started to treat her harshly and dismissively. ‘You’re mad,’ he would say. The children treated her dismissively, too, something the author remembers with sadness. Once, on a car trip to the mountains, Margaret fell – or threw herself – out of the car, landing dazed but unhurt on the road. Russel went and picked her up, and she got back in the car. ‘There ought to have been some engagement with what had happened,’ her daughter writes, ‘there ought to have been some kind words, a gesture.’ But nobody said anything.

Russel had affairs. Worse, he started to ogle every woman in sight, something that was clearly very painful to the author in adolescence. Whether or not to include material of this kind is one of the painful decisions faced by family memoirists. Margaret developed a habit that her daughter still cannot mention without revulsion, chipping away at her hands with a whole kit of tools, and covering up the results with white gloves. That is one reason ‘my mother’s hands’ are in the title. The other is that one night, when Biff was twelve, her mother came into her room at night and started to strangle her. It woke Biff up and she pushed her away, after which her mother left the room. Biff didn’t tell her father or anyone else. Perhaps (her account doesn’t make it clear) it was a memory recovered in later life. She tells the story oddly, as if describing a film clip. ‘Mum came into my room. Her shadow, flung diagonally by the light from the hall, fell across me on the bed. I didn’t hear her. I was asleep …’

When Biff was already at university, Russel wanted to go away on a year’s sabbatical and asked her to take responsibility for her mother while he was gone. He shouldn’t have done that, the reader thinks; and so does the author, though with only gentle reproach. Biff agreed, because she was the responsible daughter who always agreed, but she couldn’t do it. Instead, she got pregnant by a boyfriend who was about to depart to England on a scholarship, so they married and she went with him. Russel also took his sabbatical, sending Margaret off to Adelaide under the supervision of her family.

Russel Ward as a PhD student

Russel Ward as a PhD student

One of the saddest things in this sad book is that after she was released from the hell her family had become, Margaret got better – not fully better, but well enough to live on her own outside an institution and to behave in public no more oddly than any slightly odd old lady. So it was liberation from an intolerable situation for her as well as for them. Perhaps, if Russel had been less determined to do his duty, they would all have been happier.

Biff’s brother, Mark Ward, became an artist, and her book includes two spectacular paintings (as far as one can judge from black-and-white reproductions): Mad woman (which he didn’t initially realise was about his mother), and the later Portrait of my mother, showing a slight, elderly woman alone on a beach, clutching a large handbag, an empty sea behind her. Her hands are gloved and her eyes look sideways.

Comments powered by CComment