- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the heyday of Manhattan hotels, the Chelsea Hotel had its own special niche. The Pierre exuded wealth and exclusivity, the Plaza a sort of bourgeois glamour as the place where the bridge and tunnel crowd would throw caution to the wind and rent a corner suite for big occasions, and the Algonquin, with its round table and Hamlet the cat, radiated intellectual chic. The Chelsea had a sleazy, dangerous style, a place where almost anything went, where famous edgy artists got up to no good. It is no surprise that when, on a hot summer night in 1953, Gore Vidal and Jack Kerouac decided that they owed it to literary history to have it off, they chose the Chelsea for the momentous coupling. Even in late 1970s Manhattan, among a certain group to have sex at the Chelsea was considered almost a rite of passage.

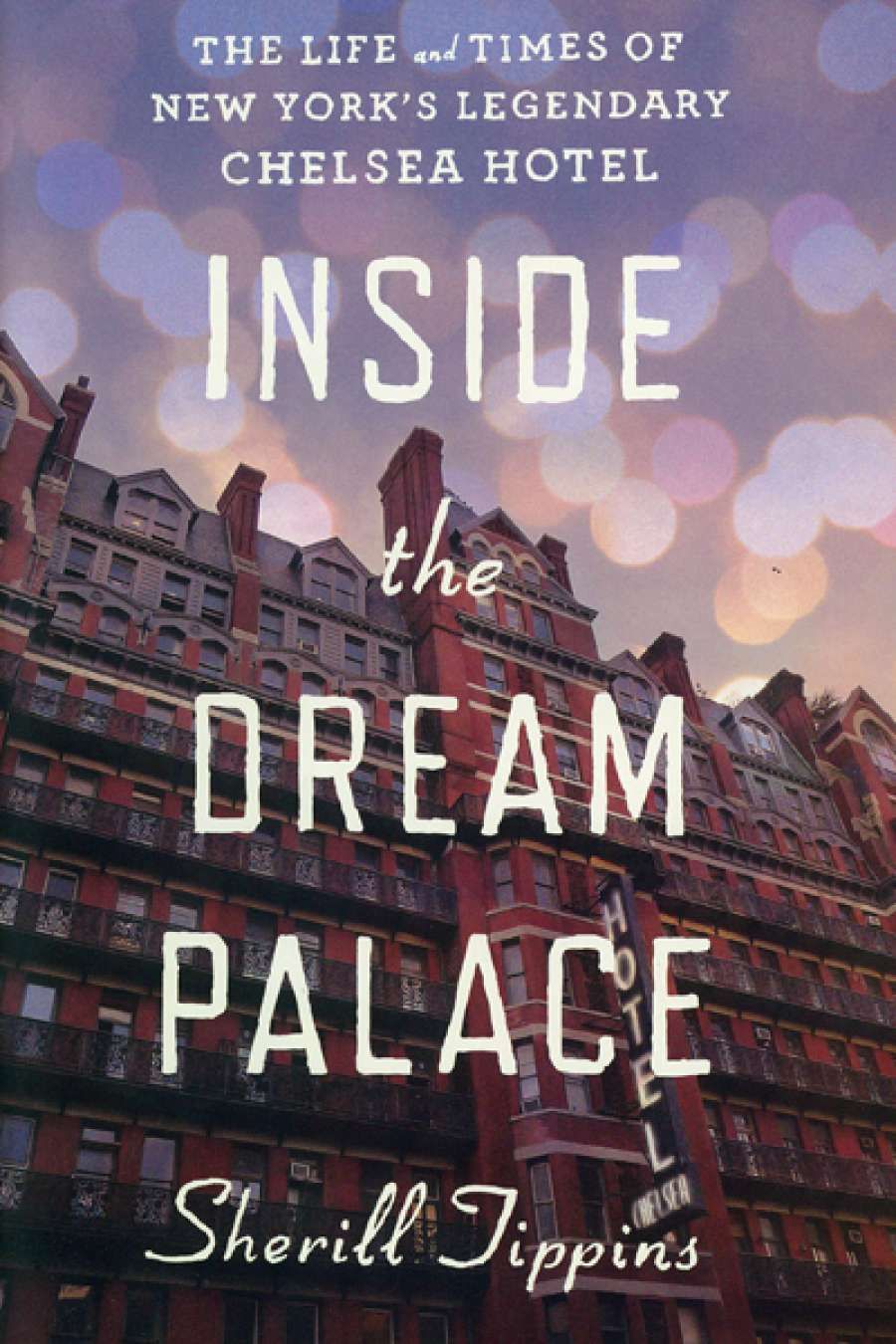

- Book 1 Title: Inside the Dream Palace

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of New York's legendary Chelsea hotel

- Book 1 Biblio: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $39.99 hb, 476 pp

Corruption and idealism were built into the Chelsea’s DNA from the start. The land on which the Chelsea stands was originally purchased by the right-hand man to the notoriously corrupt ‘Boss’ Tweed, Jimmy Ingersoll, who intended to build a huge interior design emporium on the site. No sooner was his grand showplace completed than he and Tweed were convicted and imprisoned. Shortly after Ingersoll completed his sentence, his grand edifice burned down leaving a gaping hole in the rapidly developing West 23rd Street.

The man who next organised the purchase of the block could hardly have been more different. Philip Hubert was a French-born architect who had inherited the radicalism of his father, who passed on to his son his belief in the writings of the utopian philosopher Charles Fourier. Hubert passionately believed in Fourier’s concept of ‘phalanxes’, self-contained communities of people of mixed occupations and incomes run in a cooperative style, and had already built several. The Chelsea was to be his magnum opus, and would attract people drawn to the slightly raffish, artistic milieu of the area.

At first the experiment proved to be a great success. It seemed that the mix of classes which Fourier had promulgated was working. As Tippins states, ‘who could have imagined seeing Reverend George Hepworth of the shattering anti-Tweed “God and Mammon” sermons … exchanging neighbourly nods with the nephew of the recently deceased thief James Ingersoll? Who would have believed that the sculptor and philanthropist J. Sanford Saltus, heir to a steel-company fortune, would share an address with the Dunlap Hat Company’s head hatter?’ The arts were well represented by the likes of the popular novelist William Dean Howells and the painter Childe Hassam; non-residents such as Antonín Dvořák and Samuel Clemens could be seen roaming the halls. But the 1893 and 1903 recessions hit the Chelsea hard, and in 1905 the directors converted it from an apartment house to a residential hotel. Grand apartments were split up into the varying and sometimes eccentrically shaped suites and rooms that were such a feature of the place.

Tippins nimbly skips a couple of decades and lands in the 1930s when the Fourierian ideal has been taken up by a mix of Wobblies headed by the glamorous Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and supportive artists like the writers Edgar Lee Masters and Thomas Wolfe and the painter John Sloane. Tippins also notes the arrival of the composer and critic Virgil Thomson, who, for the next half century, would blithely preside over a salon in his exquisite suite while chaos whirled around him.

Moving rapidly along, Tippins comes to the heart of her book, the decades after World War II when the building was purchased by a syndicate of Hungarian émigrés and managed first by the hotelier David Bard and then by his son Stanley. If Hubert’s plan to change the world was a series of phalanxes spread across the globe and the Wobblies’ was political action, the new groups that gathered in the old hotel had other ideas. The Beats, the New American Cinema group, and later the Punks would shatter the status quo with a combination of art and drugs both as mind-altering agents. As Tippins remarks, ‘a person could fall asleep at the Chelsea and wake up in a different era [to] … find a disorienting version of America’s nineteenth-century past with its ecstatic visions, alchemical experiments, and utopian free love’. But, as with all such dreams, this one fades, in this case into a drug-induced haze, and finally dies on the blood-stained body of Nancy Spungen in room 100.

Director Andy Warhol and actor Mario Montez at the Chelsea Hotel during the filming of Chelsea Girls, 1966

Director Andy Warhol and actor Mario Montez at the Chelsea Hotel during the filming of Chelsea Girls, 1966

Famous names fly by. Dylan Thomas and Brendan Behan pass through on a self-destructive race to the end. Alan Ginsberg briefly mentors Bob Dylan. Leonard Cohen and Janis Joplin have a fling. ‘We are ugly,’ Janis says, ‘but we have the music.’ Patti Smith hooks up with a drummer named Slim Shadow, only to find out later that he is actually Sam Shepard. The choreographer Katherine Dunham achieves the near impossible feat of being evicted when, having disturbed the other residents with noisy rehearsals of dances she was creating for a production of Aida at the Met, she decides to introduce two fully grown lions into the mix to make the rehearsals ‘more real’.

One of the more surprising occupants was that most sensible and prosaic of American authors, Arthur Miller, who moved in after the death of Marilyn Monroe to write his appalling piece of self-justification, After the Fall, and became a regular visitor. One might have thought the Chelsea would have been more of a spiritual, or at least spirituous, home to his contemporary Tennessee Williams, but although Williams wrote about places like the Chelsea, he preferred to stay in more upmarket digs.

Then there were the less well-known residents, like George Kleinsinger, whose jungle-style apartment included a monkey and an eight-foot python, or the unfortunate Brigid Berlin who took the concept of sticking around literally and passed out on a tube of glue which firmly cemented her to the floor.

The scandal of Sid Vicious’s alleged murder of Nancy Spungen sent the Chelsea into a downward spiral from which it never really recovered. After fifty years’ association with the building, Stanley Bard was fired by the board and the building was sold. In the last couple of years, it has passed from one developer to another. Now it appears likely to suffer the fate of the rest of Manhattan: gentrification. But some of the old residents are grimly holding on, and with luck something of the old place’s spirit will survive.

Comments powered by CComment