- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

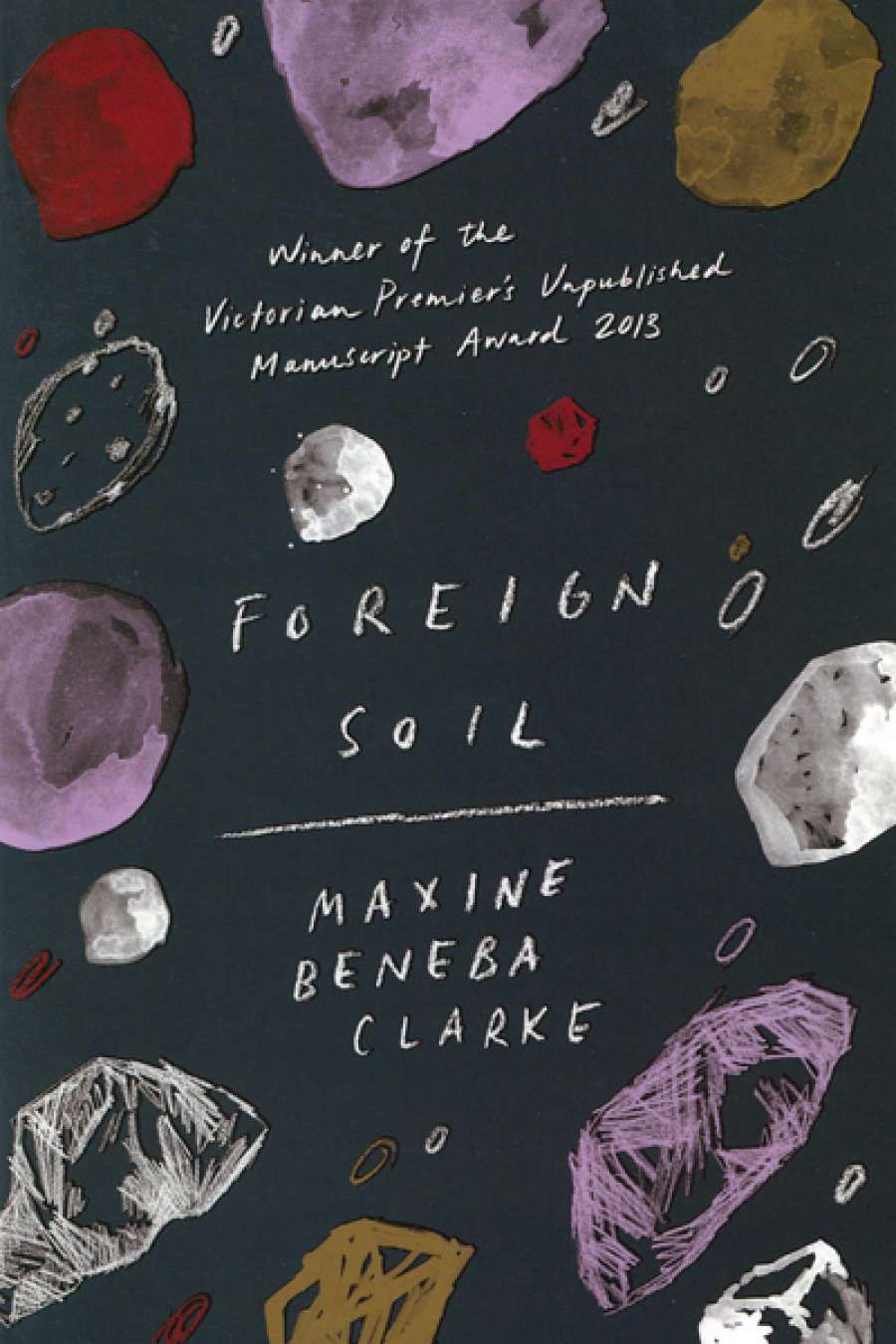

Maxine Beneba Clarke is already a well-known Melbourne voice: a fiction writer and slam poet with an enthusiastic following. Now we have her first collection of short stories, Foreign Soil – the winner of the 2013 Victorian Premier’s Award for an Unpublished Manuscript – and it is a remarkable collection indeed. While its ten stories, ranging in length from fifteen to fifty pages, are unashamedly political, they are never reductively polemical. Nourished by Clarke’s empathetic imagination, her narratives create the lived experience of suffering and despair, resilience and hope, for the powerless, the discarded, the socially adrift.

- Book 1 Title: Foreign Soil

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette Australia, $24.99 pb, 272 pp, 9780733632426

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/a1VXJM

There is an absorbing range of voices in the collection. The story ‘Harlem Jones’ captures the corrosive anger of a socially disaffected young black man in 1980s Brixton, his sentences clotted with profanities and self-deluding fantasies of fame. But if we listen more carefully, we can hear beneath his rage a plea for affirmation and a sense of purpose, a piteous vulnerability in the face of entrenched racism and class inequality. Other stories give us voices rendered in patois, a reminder of the historical link to the practice of shipping millions of African slaves to the West Indies, and the subsequent loss of the language of the colonised. In the endearing ‘Big Islan’, for example, set in 1960s Jamaica, we hear the restlessness of a black dockworker, Nathaniel Robinson, torn between a desire for the comfort of home and the expansive possibilities of a much bigger island, Owstrayleah. In a very different time and place, modern ‘white trash’ Mississippi, the story ‘Gaps in the Hickory’ gives us the entangled torment and longing of the forbidden: the boy-child Carter wishing he could dress, twirl, dance, like his little sister, wishing he could be his little sister, while digging his fingernails into the palm of his hands to punish his desire.

‘These wonderfully performative stories thus have a decidedly old-fashioned but ethically crucial aim: to refine the reader’s sympathies, to educate the heart.’

As a white Australian, the voice that affected me most was that of the young Tamil refugee, Asanka, in ‘The Stilt Fisherman of Kathaluwa’. It is the lacerating voice of trauma – often numbed, at other times hallucinatory or viscerally intense – of a young boy who barely survives a hazardous journey at sea and the degradation of the Villawood detention centre. He is the child soldier who cannot wash the blood from his body and feels he ‘deserves to die. He should have tried harder to escape.’ But there are also voices of tenderness and kindness. There is the enchantment of young love in ‘Hope’, observed by a protective, affectionate narrator. ‘Gaps in the Hickory’ gives us the voice of moral courage – steadfast, selfless – of the women who set their suffering men free. In the deeply moving story ‘David’, a Sudanese refugee mother tries valiantly to move on from the wreckage of her past.

What is also admirable is the formal diversity of the collection. Some stories use the conventional linear structure of realist fiction, while others employ the belatedness of trauma narratives. One of my favourites, ‘Hope’, cleverly blends the fairy tale, the Bildungs-roman, and the shock of dark realism to tell a story of female strength and unity. Several stories use dual perspectives to create the effect of seemingly isolated lives with hidden connections of culture or family. There is also a deft self-referential take on the role of the writer in ‘The Sukiyaki Book Club’: I was completely won over by the bracingly optimistic narrator, a woman coping with economic hardship, dependent children, and a string of patronising rejections (one imagines Clarke having the last laugh here).

These short stories also negotiate the competing demands of the genre – the requirement to be at once economical and evocative – with considerable subtlety. Clarke is particularly good at sketching in a larger social and historical context in tight narrative spaces. Like all memorable short story writers, she knows how to use the strategies of suggestion, allowing readers the challenge and the pleasure of inferring possible meanings for themselves. A couple of the stories didn’t work as well for me as others: the title story, ‘Foreign Soil’, which charts substantial changes in an interracial relationship, relies too much on explanations and summaries; its dense material seems more suited to the gradual unfolding and amplification of the novel form. The first-person narrator in ‘Shu Yi’ sounds too sophisticated, conceptually and verbally, for an eight-year-old child. Overall, though, this is an unusually even collection of intelligent, provocative, and affecting stories. Stories that stayed with me, that required several readings in order to fully appreciate their insights, emotional resonance, and aesthetic skill. They deserve the widest readership.

Clarke has two works-in-progress – a memoir and a first novel – as part of a three-book deal with Hachette. I look forward to reading more of her politically astute, bruising, compassionate writing.

Comments powered by CComment