- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tess the obscure

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

While it may not be a novel’s main purpose, certainly one of its pleasures can lie in how it witnesses the history of the form itself. All novels reveal something of the genealogy from which they emerge, their debt to past traditions and ways of storytelling. Rather as is the case with families, sometimes the further back you go the more striking the resemblance becomes.

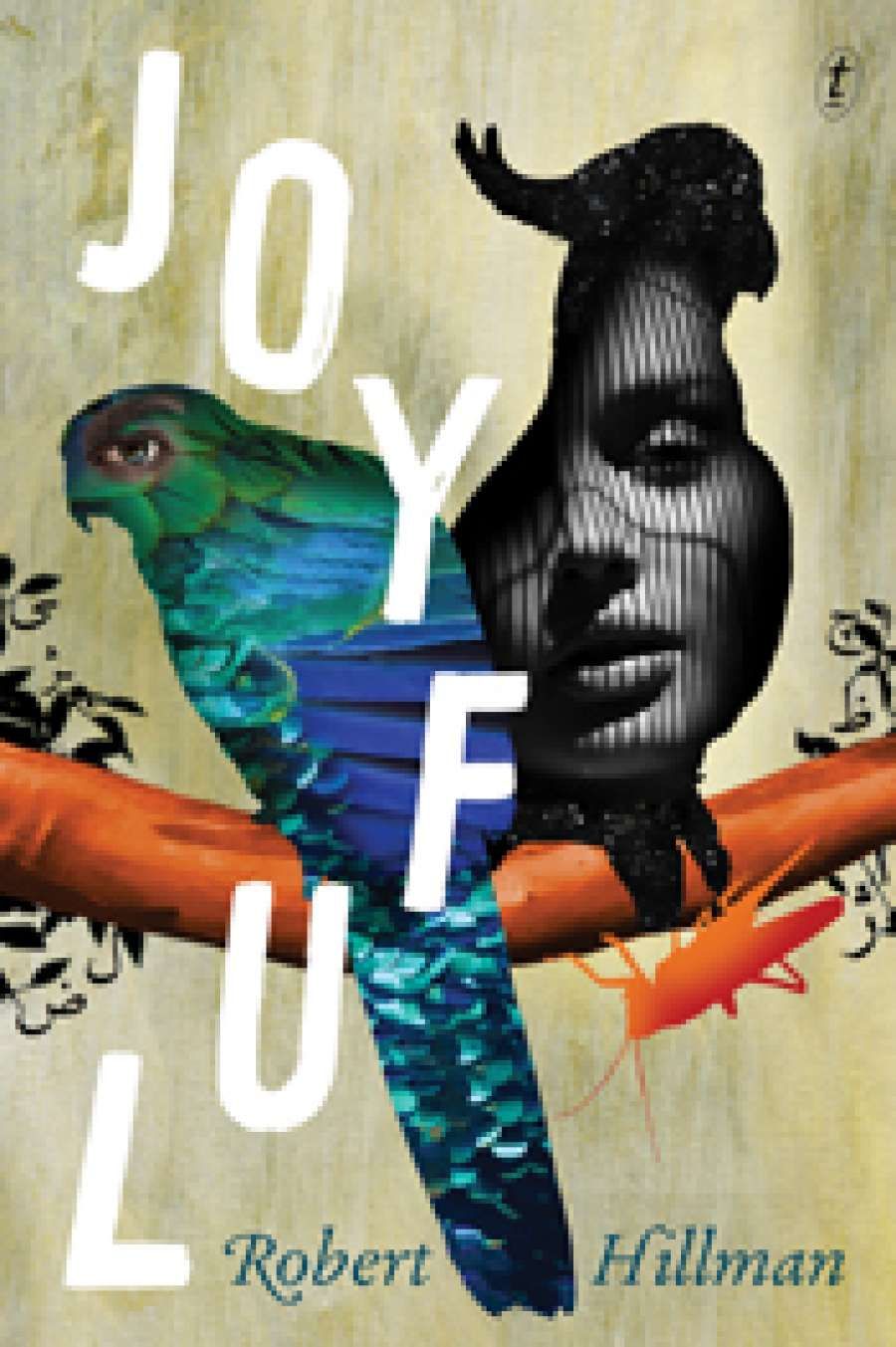

Robert Hillman’s Joyful is most immediately a nineteenth-century novel, a detailed work that portrays an entire, sealed world of complex and ultimately connected storylines. The cultural setting is realised in a wonderfully rich Victorian style. Extended studies of social manners, quotes from journals and letters, and the aligning of characters with their passions for books, poetry and music, clothing, all produce a social world that is not only vivid but also ripe for commentary and debate. In this way, the work can stand as a tribute to the likes of Trollope and Hardy, and the combination of the personal and political that they perfected.

- Book 1 Title: Joyful

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 350 pp, 9781922079916

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Kem7rN

The action takes place in a rather bookish Melbourne and at Joyful, a property given a location near the village of Yackandandah. At its core, the story pairs the lives of Leon and Emmanuel, middle-aged men from very different backgrounds who have both lost the great loves of their lives – in Leon’s case, his beautiful, errant wife, Tess; in Emmanuel’s, his two adult children. Leon and Emmanuel are not only grief-stricken but entirely overwhelmed by their losses, and the novel develops out of a sympathetic, if partly satirical, portrait of the madness that follows. We see each give up a good deal: their homes, money, social status, jobs, and their sense of personal dignity. And yet, if Leon and Emmanuel are spinning out of control, they always seem to be spinning a little closer to each other. We know that the storylines will coalesce, and that in doing so may demonstrate not only maddening loss but also the possibility of reclaiming some of what is gone.

Robert Hillman

Robert Hillman

(photograph supplied)

Loss, here, is conceived in two ways: as grief, but also as the failure of ideals that may have once attached to those who have died. Both men have experienced a kind of delight in others that they now feel is irrecoverable: Emmanuel in the intensity of his parental love; Leon in the sublime company of his wife, whose beauty, he claims, ‘was a thousand years in the making’. Leon, too, seems a remnant of a long-past society, perhaps a thousand years gone – certainly, one of much quieter and less scrutable manners (he finds physical contact with others impossible). But Tess ‘redeemed a world half given over to barbarity, torture, pain and stench’.

Rather, as we find in the moral fables and folk tales that the Victorians so loved, what Leon and Emmanuel discover now is that beauty is often the reason for a contest between how we gaze at people and how they really are. For Leon, the dangerous possibility that he has misunderstood Tess is presented to him in the figure of a Polish poet, ‘a starved dog of a man’ called Daniel. It turns out that Tess had not only been sleeping with other men – a fact to which Leon had always been reconciled – but had fallen in love with one of them. Suddenly, Leon finds himself dispossessed of his only true possession: the belief that his understanding of Tess’s beautygave her the love that she needed; that beauty formed a boundary around their Edenic home. Edens, he now discovers, are merely ‘places of intelligent denial’. Beauty wasn’t ever enough for Tess, and in Daniel she found a raw, at times brutal, erotic life that she knew Leon could barely conceive.

There is more than a touch of Emma Bovary here, and of a husband who, like the doctor of Rouen, mistakes his wife for an idea. Flaubert gets a mention in one of Joyful’s back-stories, and the conflict between an ideal of beauty and corporeality is as present in this work, as it is in Madame Bovary. Like the nineteenth-century novel and indeed many of its precursors – allegorical stories that stretch back to the Canterbury Tales and beyond – this work guides its characters through lessons that both they and the broader community in the novel must learn. Ideals can never be entirely separated from the circumstances out of which they develop; beauty is not an ideal, but rather a part of the personality of those who possess it.

For Leon, these lessons ultimately mean allowing Tess’s memory to be of both the woman he knew and the one he was yet to meet. You get the strong sense that this is the Tess that Robert Hillman would like us to know, a complex character that he may well have met in other novels and wanted to learn more about in one of his own. In another setting, she would have inspired duels and attracted more than her fair share of moral condemnation. Today, she and her admirers remind us that beauty is never entirely lost. A little like the nineteenth-century novel itself.

Comments powered by CComment