- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

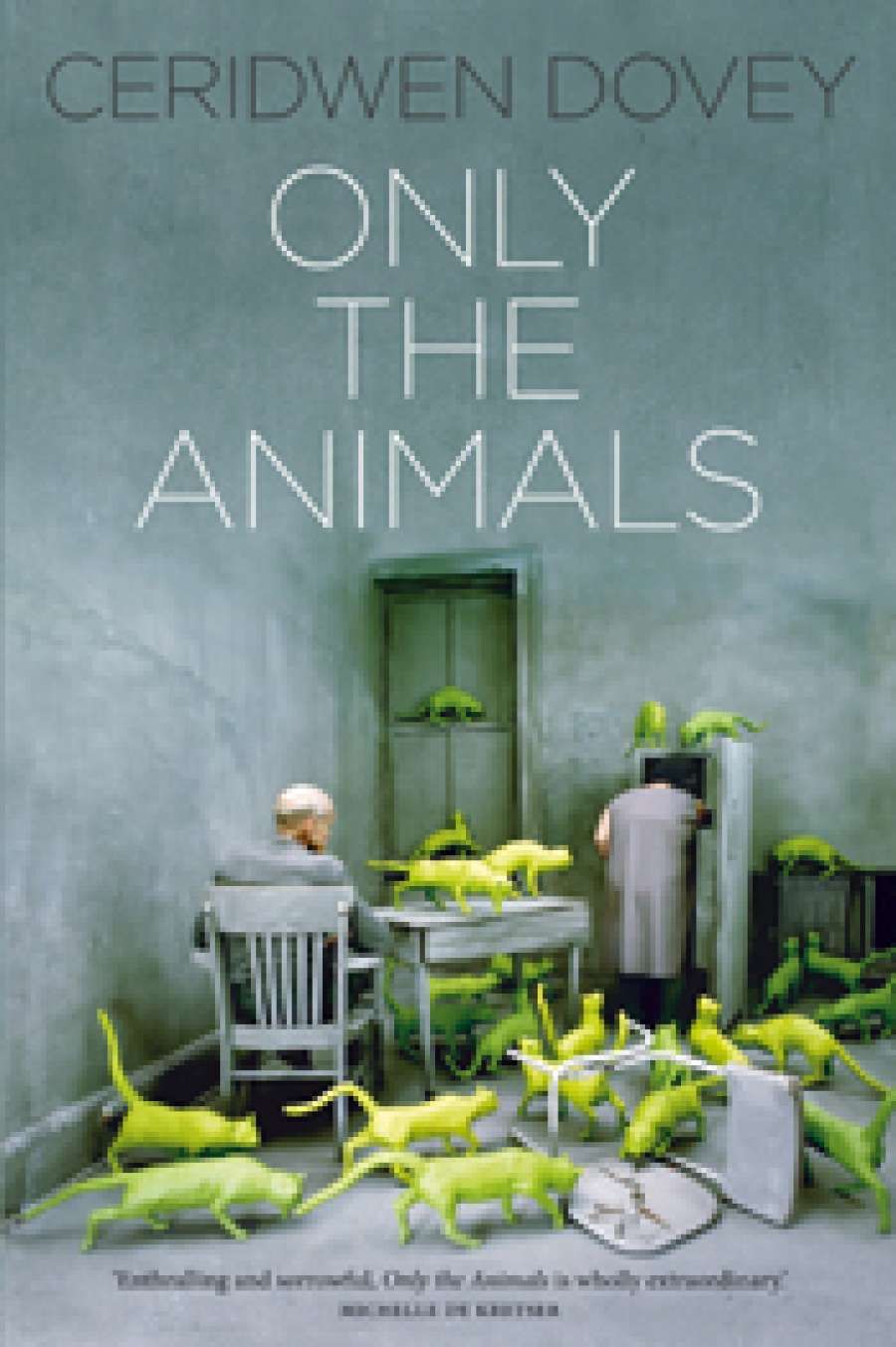

- Article Title: Modern menagerie

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the animal narrators in Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals, a dolphin named Sprout who is writing to Sylvia Plath, quotes Nobel Prize-winner Elias Canetti: ‘whenever you observe an animal closely, you feel as if a human being sitting inside were making fun of you.’ The ten animal souls whose thematically interwoven stories Dovey recounts do not simply ‘make fun’ of humans (far from it), but Canetti’s image of the ‘human sitting inside’ nevertheless provides an apposite introduction to Dovey’s project as a whole. Here each animal protagonist is an unashamedly literary, anthropomorphised invention, with physical and behavioural characteristics of its species grafted on in service to its creator’s startlingly original and imaginative design.

- Book 1 Title: Only the Animals

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $29.99 pb, 266 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4XY3O

Dovey’s first novel, Blood Kin (2007) – a fabulist tale set after a coup in a nameless country – received widespread acclaim and was shortlisted for the prestigious John Llewellyn Rhys Prize. It employed multiple first-person narrators, and won plaudits for its elegant style and meticulous construction. In Only the Animals, the author’s artistry is demonstrated by the engaging prose in each story, all but one of which are again told in the first person, and by the subtlety with which overarching images and themes emerge as the collection unfolds.

The stories are organised chronologically and, as Dovey’s website explains, share a common template. In each, the soul of an animal killed in a human conflict over the last century or so tells the story of its death, in a way that pays homage to a writer who has written about animals during the same time period.

Ceridwen Dovey

Ceridwen Dovey

(photograph by Shannon Smith)

Dovey explores this essential schema with considerable ingenuity. ‘Red Peter’s Little Lady’ is an epistolary tale set as scarcity spreads through World War I Germany. Framed as a continuation of Kafka’s ‘A Report to an Academy’, Red Peter (a chimpanzee who, in Kafka’s story, has ‘attained the educational level of an average European’) corresponds with both a female chimp being schooled to be his wife, Hazel, and the human woman responsible for Hazel’s tutelage. The lone third-person narrative is similarly located at a remove from human conflict, as two bears in a deserted Sarajevo zoo share with a witch fairy tales and their intensifying starvation. At other times, Dovey evokes animals’ experiences at the forefront of human battlegrounds. ‘Sel’ (real name Myti) is a mussel styled in the literary likeness of Jack Kerouac, who dies at Pearl Harbor. A brother of Hitler’s German Shepherd, Blondi, is cast out by its master, Heinrich Himmler, and joins the fighting at the front. And Sprout is a US Navy recruit who reflects on human–animal relations (touching on Plath’s husband Ted Hughes’s poetry), and recounts her experiences with naval forces during the two Gulf Wars.

The stories are assiduously researched – a list of sources is published on Dovey’s website – and the historical and zoographic details are persuasive. Dovey’s ambition to address other animal-themed writings can make the style more self-conscious than is the case with her best writing. The memoir of Plautus the Tortoise, who encounters various literary and philosophical luminaries before joining the Soviet space program, is an example. Sprout’s letter is occasionally strained in the same way.

Bear in Ähtäri Zoo, Finland

Bear in Ähtäri Zoo, Finland

(photograph by Tiia Monto)

Some contemporary readers may also find Dovey’s use of animal narrators challenging. Philosopher Thomas Nagel questioned whether a human can ever know what it is like for a bat to be a bat; in J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals (1999), Elizabeth Costello’s response is that a human can think her way into the existence of any being with whom she shares the substrate of life. In neither design nor execution does Only the Animals attempt to transport human imagination into the phenomenological reality of animal existence. Dovey’s animal protagonists possess quintessentially human ways of understanding: a camel who tries to face Mecca; a tomcat who recognises that Colette ‘always circles back to her [mother] in her writing’; a dog who becomes a vegetarian to attract good karma; a tortoise whose head ‘ache[s] with pleasure’ at a Bertrand Russell astronomy lecture. The criticism that humanised animal characters reinforce anthropocentrism by parodying animals is specifically foregrounded by Sprout: ‘I said I’d participate only if I could use the third person, to avoid becoming a parody of myself, the self-aware dolphin wielding “I” like a toy ball propped between my fins. But as it turns out, “I” is irresistible.’ Yet, from one view, making animals parodies of themselves is precisely what Dovey does.

The reality is more complex, however. Dovey is a natural storyteller, and her skilled use of animal ‘others’ to highlight discrete aspects of human conflicts throws the obscured, terrifying whole into stark relief. The author’s portrayals of human–animal interactions evoke images of lasting beauty and power: the selflessness of animals who go hungry so that starving soldiers can eat, or for whom death is preferable to killing a human; forms of love between humans and animals both sanctioned and taboo; the sense of belonging inspired by seeing forebears inscribed among the stars.

It may be that ultimately Dovey provokes empathy because her animal subjects are humanised: shape-shifting intermediaries who facilitate visualisation of how humanity might be perceived from some external, yet equivalent perspective.

Whether you agree with Dovey’s approach to humans and animals or not, no one interested in either will be sorry to have read this book.

Comments powered by CComment