- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Amy Baillieu reviews 'Letter to George Clooney'

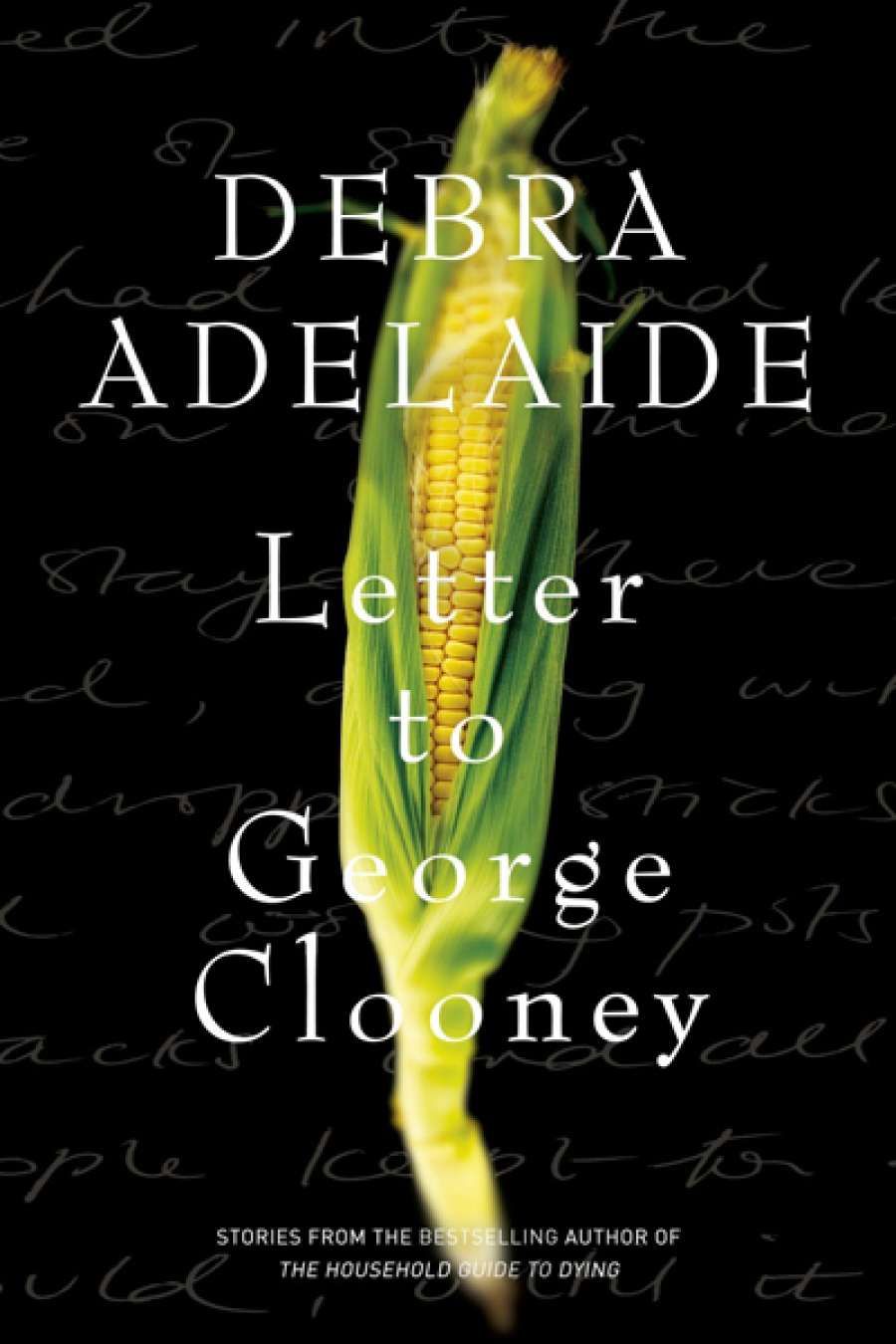

- Book 1 Title: Letter to George Clooney

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $24.99 pb, 295 pp, 9781742613093

Letter to George Clooney represents a departure for Adelaide, not only in form but in outlook. Although most of the stories are set in Australia, there is a fresh international feel to this collection of thirteen short stories. They cover such diverse territory as writers’ festivals, war-torn Darfur, a visit to the ATO, and the tribulations of modern dating. Some of these stories are so distinctive in tone, style, and voice that it is easy to forget they are all by the same author, but there are common themes and preoccupations, among them writing and the different aspects of love.

Writing is central to the opening story, ‘The Sleepers in that Quiet Earth’, in which a woman reads Wuthering Heights to her dying mother and meditates on the nature of creativity and inspiration as she begins to write her own novel, and to ‘The Moon Will Do’, in which a mother copies chain letters with desperate optimism as she struggles to deal with her child’s illness. It is also integral to the wry comedy of ‘Glory in the Flower’, where ‘Bill’, a ‘distinguished British Poet’, arrives in Australia to teach a poetry masterclass as part of the fictional ‘Riverside Literary Festival’. One of his students is Louise,‘whose portfolio included three short poems all in rhyming couplets on the topics of washing up, pruning roses and a barbecue. She had rhymed “sausages” with “partridges”.’ Read superficially, this is a somewhat pompous depiction of the gap between writers and those who aspire to become them. However, once the reader deciphers Bill’s true identity, the narrative takes on a joyous absurdity.

The gap between established authors and ‘potential’ writers is explored from the other side in ‘Writing [in] the New Millennium’. A woman attends a writing program, expecting ‘hours and hours of blissful intensive hands-on work’, but doesn’t receive the practical guidance she was hoping for (‘sessions on the problems that bothered me, such as choosing names for characters and keeping my desk tidy. Or advice on posture and diet’), instead encountering contradictory advice and the dispiriting counsel that writing (‘like picking your nose, or masturbating’) isn’t something one should admit to in public.

Literary capers are also central to ‘If You See Something, Say Something’, the story of a Sydney semiotician and compulsive reader, seeking love amid the LRB personals. At one point, during her correspondence with a man who is looking for a travel companion with ‘the ability to mend a Kombi van with a hairpin and duct tape’, the narrator reflects that ‘bad writing. Boring writing’ is the ‘worst crime’.

The LRB personals, with their ‘obscure neuroses and wittily inflated egos’, are just one of the different permutations of dating and relationships examined here: in ‘The Pirate Map’ a sculptor tentatively woos his highly efficient and inscrutable accountant, while the narrator in ‘Harder than Your Husband’ observes his new employee’s brashly materialistic relationship with her fiancé, in which expensive vacuum cleaners and modified commodores are given as nuptial gifts. ‘Chance’ reveals the mundane perils of online dating: a woman finds herself on a weekend away with a man whose repugnant personal rituals begin to make her unappealing former lover seem attractive by comparison.

There are gentler stories in this eclectic collection which offer quiet romance (‘The Form of Solemnisation of Matrimony’) and subtle humour (‘The Harp Society’), but the strongest inclusions are the macabre and touching ‘Virgin Bones’, in which a family finds domestic bliss, of sorts, living inside a mausoleum, and the title story. Adelaide has a knack of subtly withholding key details so that the reality of a story’s setting or context is not immediately apparent; the latter builds gradually from descriptions of everyday frustrations, such as waiting in a ‘torturously slow’ supermarket queue, to revelations of such shocking brutality that later the narrator remembers a time when ‘it was bliss to discover people only suffering from HIV, malnutrition and tuberculosis’.

Adelaide is a keen observer of humanity, and so are many of her credible and idiosyncratic protagonists, who often muse about the imagined lives of others. Adelaide also continues her predilection, first evident in Serpent Dust and then used to great effect in The Household Guide to Dying, for weaving extracts and samples from other texts (both fictional and real) into her own narratives. Her stories also contain frequent allusions to literary and popular culture (from Kafka to Frank Zappa) and reveal a slightly disconcerting preoccupation with the teeth of handsome men. The stories in this entertaining collection are thoughtful, funny, brutal, and shrewd. It is the perfect showcase for Adelaide’s wide-ranging intellectual sensibility, lightly worn research, and literary flair.

Comments powered by CComment