- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: China

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Celebrity dead or alive

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

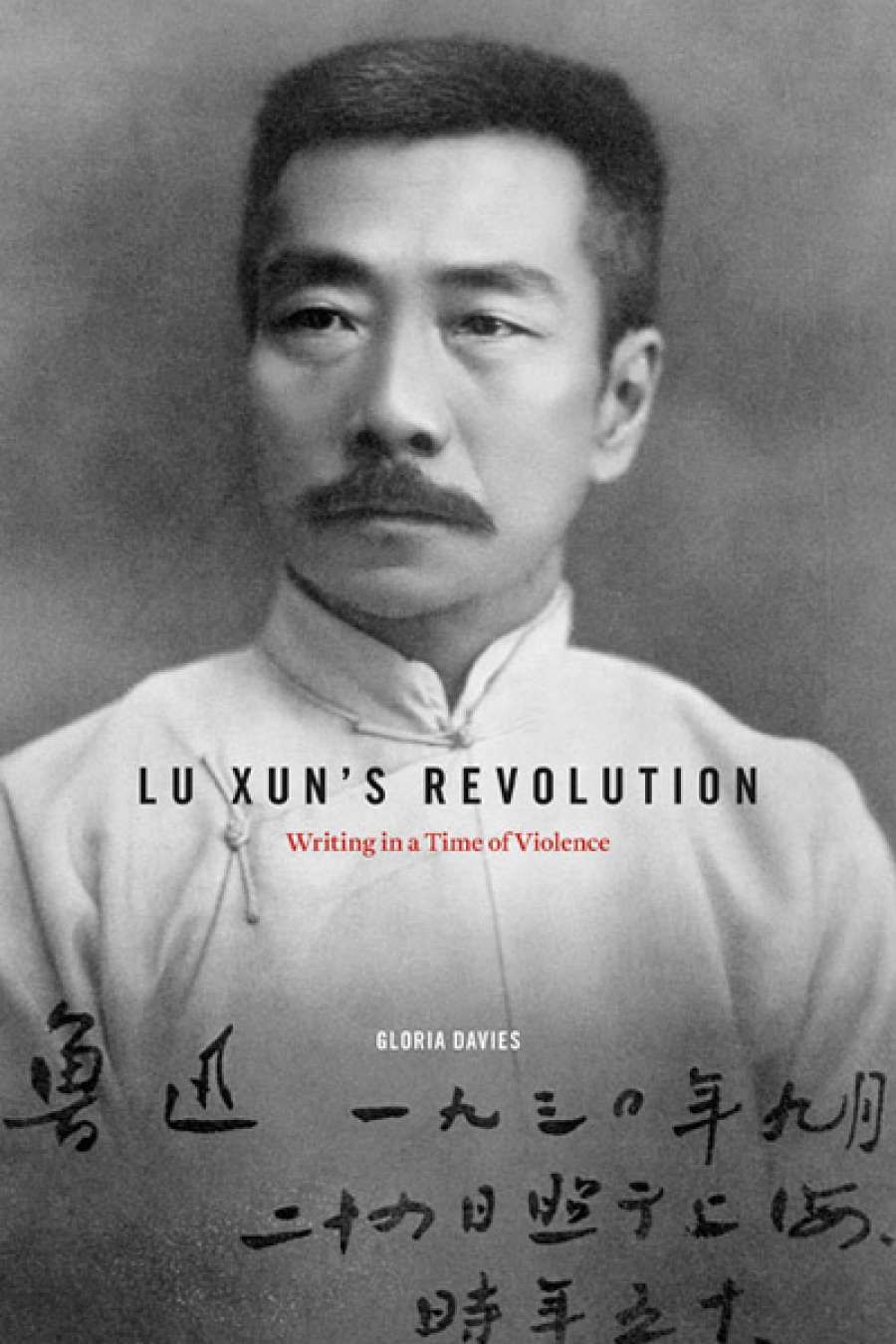

This richly documented study of China’s pre-eminent writer Lu Xun (1881–1936) by Gloria Davies cannot fail to provoke deep reflection on the issue of the creative writer, artist, philosopher, or scholar and his or her involvement in politics. For Lu Xun, the issue was exacerbated by the brutal reality of China in the late 1920s and early 1930s, a ‘time of violence’, as suggested by the book’s subtitle. Highly emotive patriotism had generated political activism, and abstract ‘revolution’ had an uncanny religious aura with its promise of an ideal future society. Violence came from an intense struggle for power, and political parties were defined by an army and an extensive network of informers and assassins: public and secret executions instilled fear in the faint-hearted and, at the same time, produced heroes who were prepared to sacrifice themselves. Intellectuals were recruited into the propaganda machinery of the Nationalist Party or the Communist Party, and individuals had no option but to adopt a political stance.

- Book 1 Title: Lu Xun's Revolution

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writing in a Time of Violence

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press (Inbooks), $49.95 hb, 434 pp, 9780674072640

Although Davies’ book is about China and tells of a time far removed, Lu Xun’s incisive critique of human behaviour continues to resonate with truth for readers today. His works were translated into Russian and Japanese during his lifetime and have been familiar to the English-speaking world since the 1956 publication of the four-volume Lu Xun: Selected Works, translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang. The Lu Xun who comes alive in this book is human and not the godlike figure force-fed to generations in China after his death.

Readers may be startled to learn of the cosmopolitanism of Chinese writers who accessed European, Japanese, and Indian writings via translations. Lu Xun himself translated Marxist texts from Japanese translations and had completed a large part of Gogol’s Dead Souls from a German translation when he died. Readers will be reminded that both nationalists and communists alike resorted to murder and assassination to destroy political rivals either within their own ranks or within the enemy’s. In the West, the Cold War has virtually obliterated from memory the extensive killings perpetrated by the nationalists during their drive to exterminate communists; another reason for this historical amnesia may be that those killings were subsequently eclipsed during Mao’s régime.

Davies scrutinises the many dimensions of Lu Xun’s ambivalent support for the communists. He did not join the Communist Party, and moreover argued for pluralism within the party; he had close friendships with a number of individual communists, but had no qualms in attacking doctrinal purists for writing about Marxism just to satisfy the demand for revolutionary writings by the publishing world. Such purists frequently attacked Lu Xun, for, as Davies notes, to attack a literary icon of Lu Xun’s stature elevated one’s position in the literary world as well as within the party. Lu Xun was keenly aware of how his celebrity status was being used in this way, and feared how it would evolve. The party leadership soon identified Lu Xun as an asset, and ordered the cessation of attacks on Lu Xun. On Lu Xun’s death in 1936, Mao Zedong immediately co-opted the deceased writer to his cause. Lu Xun could not have foreseen how the literary debates of those times would later be used to transform him into a communist hero, and also be turned into evidence against Mao’s enemies. Selections from his writings were sacralised and used to instil a spirit of self-sacrifice for the nation and the party.

Lu Xun’s story is infused with a strong sense of the literary. Copious excerpts from his work testify to his extraordinary mastery of language, powerful intellect, and inimitable wit. Lu Xun had enjoyed celebrity since the publication of his short story ‘A Madman’s Diary’ in 1918, followed by others that were collected in Call to Arms (1922) and Wandering (1926). ‘A Madman’s Diary’ was written in the vernacular language and was a harsh indictment of Confucian teachings as being cannibalistic, the root cause of China’s failure to modernise. Lu Xun’s stark metaphorical image encapsulated the demand of radicalised Chinese youth to destroy traditional Chinese culture. As traditional culture was transmitted in texts written in the classical language, this led to the discarding of both China’s entire literary heritage as well as the language in which it was written: China’s modern literature had to be written in the vernacular language. ‘A Madman’s Diary’ fulfilled these criteria, and Lu Xun was acknowledged as the undisputed leader of a younger cohort of writers who together laid the foundations of China’s modern literature.

China’s continuing failure in the modern international world was damaging for the Chinese psyche. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, China’s contribution of 140,000 labourers to the Allied war effort was ignored and the former German ‘colony’ of Qingdao was handed to Japan. Chinese intellectuals who had worshipped the liberal democracies of the West felt betrayed, and it was to Russia that many of them turned. In other words, the liberal democracy model had been seriously diminished.

On 1 January 1912, Sun Yat-sen (1886–1925) announced the birth of the Republic of China that anticipated the establishment of a representative parliamentary system of government. However, without the backing of a powerful army the fledgling republic splintered into warlord kingdoms. In 1921 the Chinese Communist Party was established in Shanghai, with direct links to the Comintern. At the same time, the Nationalist Party led by Sun Yat-sen was reorganised with the help of Russian advisers; in 1924 it admitted communists into its ranks for a concerted action to crush the warlords. Sun’s death in 1925 allowed Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975) to assert his authority as commander of the National Revolutionary Army, and in 1927 he led the Northern Expedition to complete Sun’s mission of national unification. Chiang, a military man, did not share Sun’s idealism: in April 1927 he orchestrated a surprise purification of the party by purging it of communists, and then a nationwide hunt for communists. According to figures cited by Davies, from April to December 1927 suspected communist prisoners numbered 32,316; a further 37,985 had been condemned to death. In the meantime, Japan continued with impunity to encroach on Chinese sovereignty, positioning itself for a full-scale invasion that would begin in 1937 and last until 1945.

Davies alludes to Lu Xun’s sacrifice on behalf of China’s youth, but does not specify the nature of his sacrifice. It was in fact his creative self. A reading of his collection Wild Grass (1927) as a single work, including the preface, indicates that these poems document his decision to terminate his creative life. Like his one-time mentor, Zhang Taiyan (1868–1936), Lu Xun was an uncompromising individualist in the Daoist sense and experienced trauma because of his empathy with the people. It was for this reason that both men had no option but to become involved in politics. Their unwavering belief only in their own assessment of external reality made it impossible for them to be dictated to by others. Both being totally unsuited to politics, they were doomed to fail.

Although brilliant stylists in the classical language, Lu Xun and Zhang Taiyan did not hesitate to write in the vernacular language when they believed it would benefit the people. On 10 March 1910, Zhang Taiyan began publishing Education in Present-day Language Magazine. The targeted readers were the common people; he wrote in lucid vernacular language. The aim of the magazine was to foster learning and scholarship, and to assess China’s traditional cultural heritage. For him, no texts should be treated as sacred. Davies has highlighted Lu Xun’s commitment to the people and to vernacular language writings reaching the people. Zhang Taiyan was a celebrity because of his powerful writings in the first decade of the twentieth century. He too lived in a time of violence, when key persons attempting to establish the institutional framework of the young republic were assassinated. But Lu Xun’s reality was one of mass murders, and also the perfection of a propaganda machine that would victimise him cruelly after his death.

Comments powered by CComment