- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Brian McFarlane reviews 'Stage Blood'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Power play

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Anyone lucky enough to have read Arguments with England (2004), the first volume of Michael Blakemore’s memoirs, will be eager to read the second, Stage Blood, in which he traces the tumultuous history of his years at London’s National Theatre. Further, anyone as lucky as I was to see such productions of his as Long Day’s Journey into Night in 1971 will be agog to read the new book in the hope of insights about their genesis. Such people will not be disappointed.

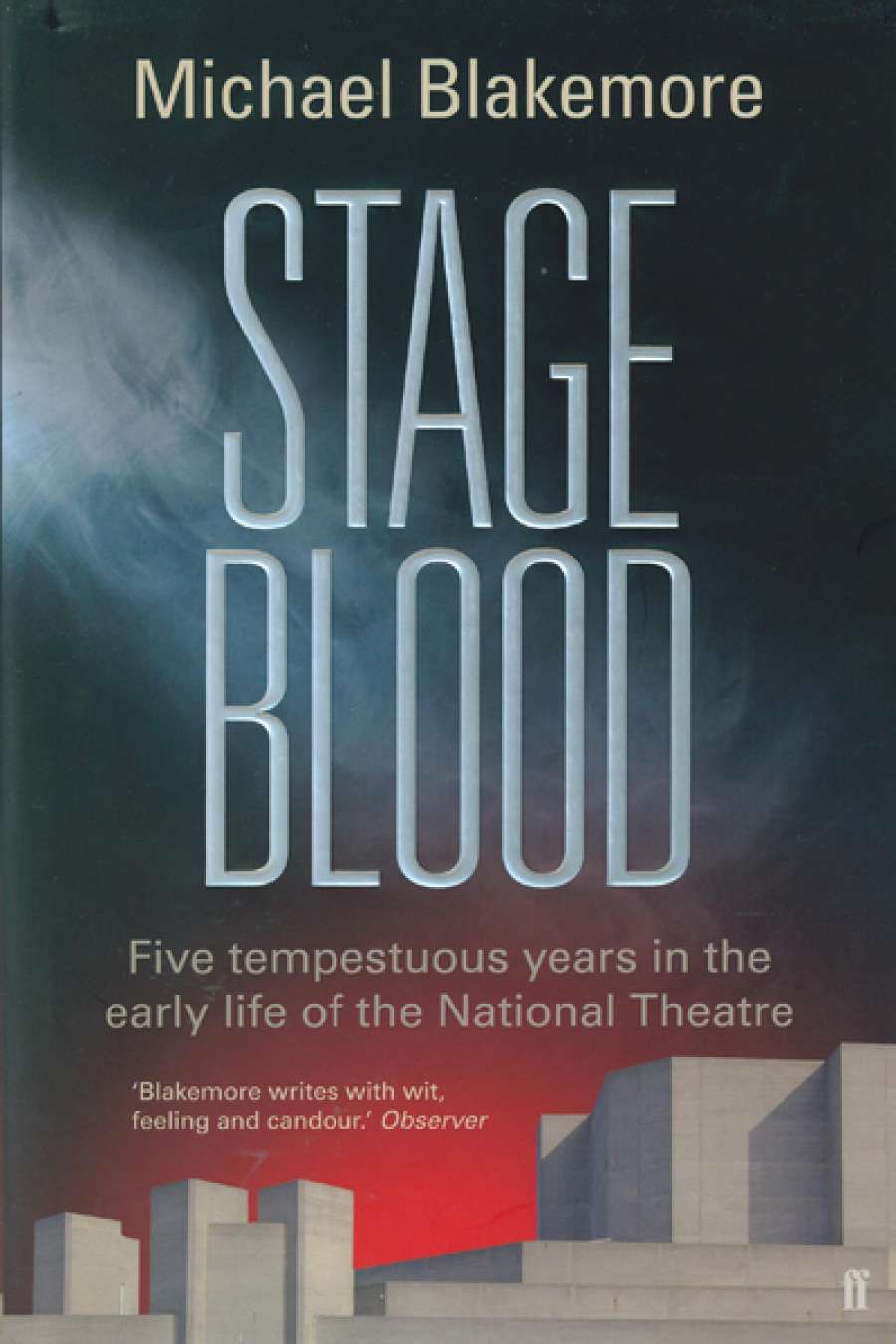

- Book 1 Title: Stage Blood

- Book 1 Subtitle: Five Tempestuous Years in the Early Life of the National Theatre

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber and Faber, $39.99 hb, 367 pp, 9780571241378

In so far as Stage Blood is a memoir, it is primarily a chronicling of a professional life with no more than fleeting glimpses of the domestic. Blakemore gives a wonderfully acute sense of what it was like to direct Laurence Olivier in Long Day’s Journey. He was sympathetically attuned to the ageing actor’s difficulty with his lines, what it was like to be in rehearsal with him, and how the other actors responded to the legend and to the reality. ‘Something important, for all of us, for the National Theatre, was at stake but we couldn’t take it for granted.’ There is an enthralling account of the tensions leading to the opening night, the progress and the anxieties. This is where the heart of the book is to be felt, as distinct from a mere listing of press responses.

But it isn’t just high dramalike the O’Neill that Blakemore brings to life in its making. He is vividly evocative about, say, finding his – and his collaborators’ – way through Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page, and gives a sharp sense of what attracted him to this comedy of tough-talking newspaper guys waiting in a court press room to cover a hanging. As with Long Day’s Journey, Blakemore invites the reader to share in the ways in which the strengths and challenges of a play can be identified – and met. It’s not that he skimps on the actual performances as audiences saw them, but it’s the evocation of the creative efforts involved – not just of his own, but of his actors as well – that is so rewarding to read.

However, the subtitle, ‘Five tempestuous years in the early life of the National Theatre’, is no mere gesture. The three-auditorium, concrete-girt National Theatre on London’s South Bank was finally opened to the public in March 1976, its opaque façade giving no clue to the sorts of off-stage dramas that had preceded the gala. Blakemore – who gained experience as a repertory actor in England in the 1950s on leaving Australia, and as a director, notably of Peter Nichols’s plays, A Day in the Death of Joe Egg and The National Health – joined the National when it was still playing in other venues such as the Old Vic. At this point, Olivier was in charge as artistic director. Blakemore is astute and even-handed in his view of how the great man ran the place. Olivier had always been his hero, and he never lost his reverence for what, at his best, the actor could achieve. He was also conscious of ‘the effusive theatrical Larry, larding his correspondence with flowery endearments’ (he regularly addresses Blakemore as ‘boysie’), and that ‘in a treacherous profession [he] had an aching need for real friendship, as well as the steel to forgo it if it was a check on his ambition’. Not many of Olivier’s biographers, including the most recent, Philip Ziegler, have been so subtly aware of how the actor ticked; not many have retained admiration and indeed affection for him despite his treachery, Blakemore’s experience during the televising of his Long Day’s Journey.

In fact, his complex feelingsfor Olivier long outlast their tenure at the National. Whereas the biographies have often made us privy to the nastier possibilities of egoism and narcissism in the actor, Blakemore, aware of these proclivities, remains generous enough in his concern for Olivier’s increasingly infirm old age. And in his successor, Blakemore will find a man who, for all his capacities, undermines the concept of the company that Olivier had sought to create.

There is a powerful sense of the play of personalities at work in the establishment and running of the National Theatre. By the time Blakemore has finally resigned from his position as associate director, he has seen Olivier unseated to make way for Peter Hall. Watching Hall at work helps him to redefine words like devious and rapacious. As Othello said, ‘A man can smile and smile and be a villain.’ Well, perhaps ‘villain’ is a little more severe than Blakemore intends, but there is a powerful sense of self-serving and greed at work in the way Hall emerges, and Blakemore takes issue with how Hall represented the conflicts of these years in his published Diaries (1983), which seems often to have but a casual connection with the truth of the occasions recorded.

The latter is especially the case in theDiaries account of the events leading up to Blakemore’s resignation. He submits a long paper to the National’s advisory board, taking meticulous care to avoid leaks about its substance, providing copies for each of the board’s members, with debatable suggestions about the National’s operating policy. These included matters of salary inequities among actors and questions about directors on full-time salariesaccepting lucrative television or theatre work, as Hall himself notably did. The upshot was that Blakemore’s salary was stopped without notice and he ‘was simply being put in a position where it was impossible to stay’.

The backstage politics of the National’s administration make the recent history of the Australian Labor Party sound like two Sunday schoolteachers disagreeing about the site of the annual picnic. The drama potential alone in the offices of the National Theatre would be enough to ensure the attention of most readers, but what Stage Blood also has going for it is an author who is not merely a famously gifted director but who is also a stylist of the most elegant precision. In bringing to life the dramas of the rehearsal room, the stage itself, and the corridors of power and the power-seeking, Blakeman has fashioned a gripping narrative. The fact that he writes with an admirable restraint works in favour of intensifying the conflicts and of inclining the reader to accept as fair his view of proceedings, where hysterical hyperbole might have had the opposite effect.

There is not much room for the author’s domestic life. With wife and son, there are interludes in Biarritz where Blakemore takes on the renovation of an old house, so that he can indulge his love of the seaside. Well, he did once make a film called A Personal History of the Australian Surf (1984), and his passion for the waves comes through vividly. Towards the book’s end, there is cursory reference to how his health and personal life fell apart, but it is the energising conflicts of the preceding decades that make Stage Blood such a great read.

Comments powered by CComment