- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Worlds within words

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

All scientists are writers. Science only exists in the written form. What is not written is not published, is not accepted, is not knowledge, and does not exist. It is written science that is scrutinised, peer-reviewed, and cited – nothing else matters but to ‘publish or perish’. Scientific articles, in all their clever, compacted, content-laden complexity, may well be impenetrable to all but the most specialist reader, but this does not mean they are poorly written. Articles are extraordinarily difficult to craft; writing them is the hardest and most intellectually challenging aspect of scientific practice. Evidence – the experimental result or the novel observation – may well lie at the heart of science, but until this evidence is written up and published it remains an unpolished gem which cannot be appreciated or understood. Through the medium of the written word, science has taken us to new worlds. Charles Bazerman argues that ‘scientific writing is one of the more remarkable of human literary accomplishments … [and has] literally helped us move mountains and to know when mountains might move on their own’.

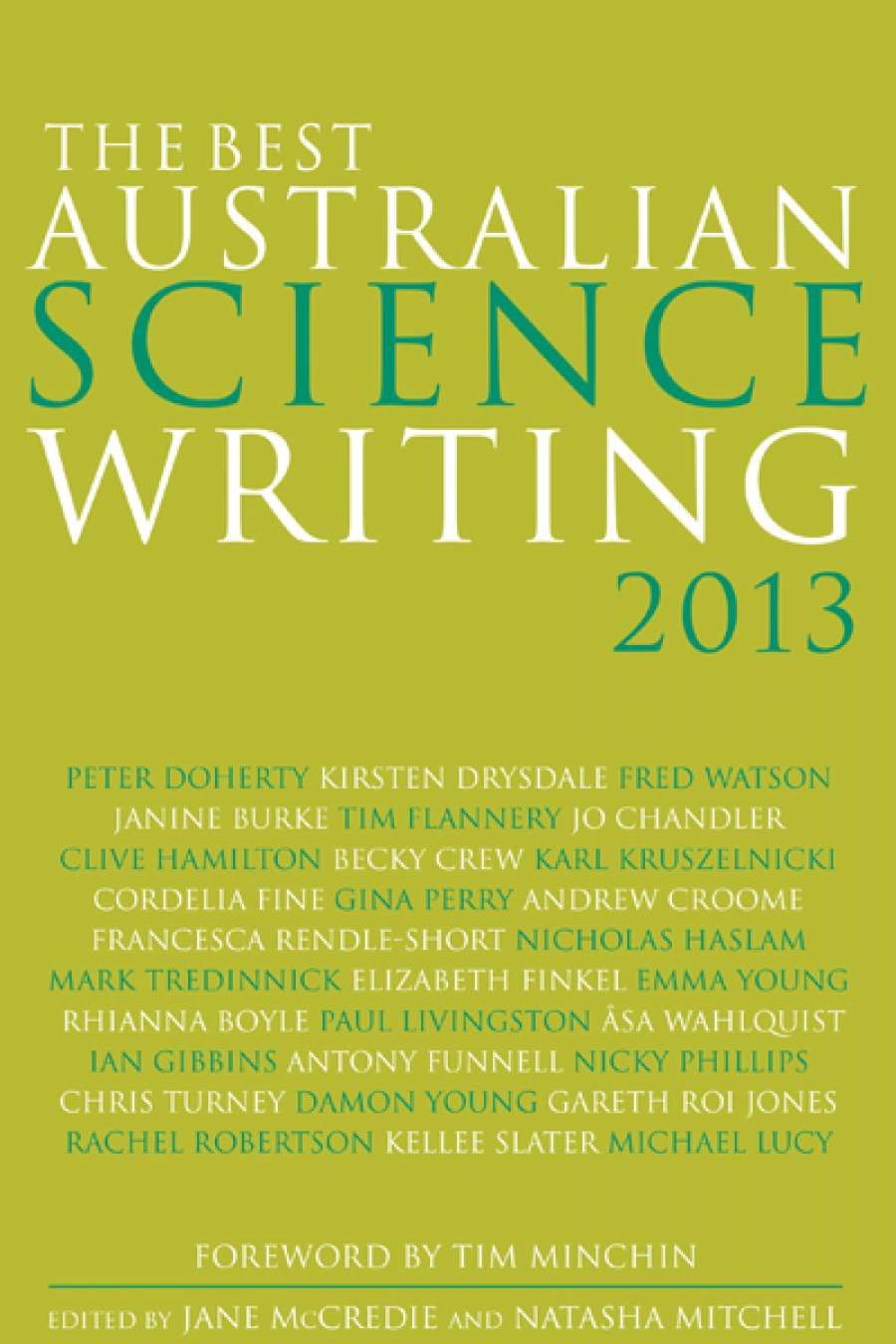

- Book 1 Title: The Best Australian Science Writing 2013

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth Books, $29.99 pb, 309 pp, 9781742233857

But the role of scientific writing extends far beyond the realm of academia. Advances in science are often made, not by persuading scientists of their merits, but by appeals to the general public. Major advances in science (such as Darwinian natural selection and Linnaean taxonomy) have often been taken up, not so much on the basis of their scientific merits (acknowledgment may take years to accumulate), but on the basis of popular books promoting their ideas. By contrast, climate-change debates illustrate the barriers faced by scientific evidence when it is not supported by public opinion.

When we think of science writing, we often think only of the two extremes – academic writing and science journalism – but science writing operates across a diverse range of forms, from the lightweight and trivial to the hard-hitting and profound. The latest anthology of The Best Australian Science Writing 2013 reflects that diversity. Here we have personal memoir, pop science, poetry, and essays; philosophical meditations, creative non-fiction, and considered reflections; journalistic reportage and first-person immersion, although, sadly, no scientific articles themselves. Most contributions are from writers and journalists, perhaps reflecting the background of the editors, although a significant proportion come from writers with scientific training. A much smaller number come from practising scientists.

A solid core of contributions falls comfortably into the genre of classic science writing, particularly those by Cordelia Fine, Rhianna Boyle, Emma Young, and Karl Kruszelnicki. Others write from the interior view; Michael Lucy reports on science reporting as a science reporter, while Peter Doherty, Fred Watson, and Nick Haslam provide accounts from their own perspective as scientists.

The first-person account certainly seems to make a strong impression in this collection. This ranges from the immersive journalism of Ella Finkel and Gina Perry, in which the journalist–researcher is present within the recount of the story, to the powerful firsthand account of surgeon Kellee Slater’s experience of donor-organ recovery. Less successful to my mind is the inclusion of personal memoir, which sits uncomfortably in the collection. The exception is Rachel Robertson’s fine personal essay on mathematics and autism.

Many of the contributions are extracts from larger works, giving the collection, when read from beginning to end, a slightly fragmented, schizophrenic feel. I often wanted more context. Who is writing this? Who are they writing for? With the biographical information clustered at the beginning of the book and the sources at the back, this made for much flicking back and forth. The longer pieces provided a welcome relief from the sometimes frenetic shifts in pace, which were possibly exacerbated by the juxtaposition of different forms. Consider the long sweeping paragraphs of Clive Hamilton’s reflections on climate change, or the nuanced and considered discussion of kuru by Jo Chandler, compared to Nicky Phillips and Åsa Wahlquist’s almost telegraphic paragraph structure.

Having said that, the interspersing of the prose extracts with poetry by Ian Gibbins and gareth roi jones was inspired. This was a well-signposted change of pace that was enjoyable rather than disruptive, perhaps because the change in form was so readily identifiable.

Some contributions required a very broad definition of science writing. Is Chris Turney’s discussion of Antarctic exploration about history or science? Likewise, Antony Funnell’s discussion of efficiency and Kirsten Drysdale’s story on data-mining seem to stretch the definition somewhat. But stretching the definition is perhaps better than being too narrow. A narrow definition might not have allowed the inclusion of Mark Tredinnick’s lyric prose on weather, Andrew Croome’s evocative descriptions of place, or Janine Burke’s meditations on nests.

The best contributions synthesise complex concepts with exquisitely concise detail, compact enough to hold in one hand. Science writing for a general audience allows us to connect through emotion, as well as intellect, and no one illustrates this better than Tim Flannery. It will be a long time before the death of the last Christmas Island pipistrelle fades from my mind. Carefully wrapped in metaphor and familiarity, these contributions are precious gifts of comprehension, bringing light and beauty to what might have remained in darkness and bringing us a richer appreciation of the complexity of our world.

Comments powered by CComment