- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Kathryn Koromilas reviews 'The Antibiography of Robert F. Menzies'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Above the line

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

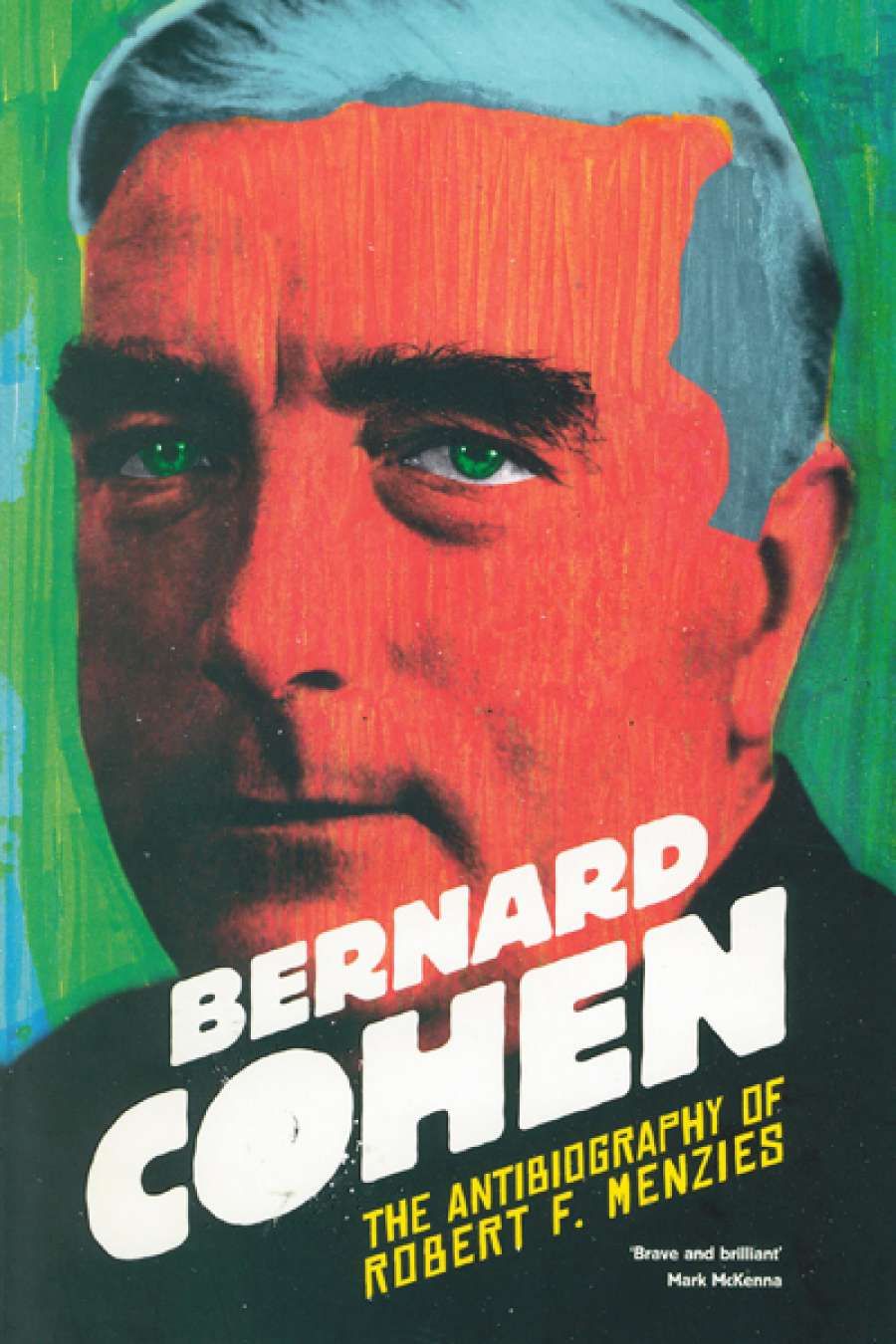

Above the line’, a narrator begins a story. At a specific moment in time, a specific fictional character appears and something is about to happen. ‘Below the line’, another narrator begins a different story, a story in notes, footnotes, ‘citational backup’ for the story ‘above’. You have begun reading Bernard Cohen’s new novel: a work in story and notes, a game, a play of genre, a performance. - Book 1 Title: The Antibiography of Robert F. Menzies

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 298 pp, 9780732264383

‘Above the line’, the character is Robert Menzies – or, at least, the character resembles Menzies. The novel is set in the early years of the Howard government and is prompted by the pre-1996 election ‘Headland’ speeches in which Howard invoked Menzies as a symbol of a benign Australia content with its own prosperity and guiltlessness. With his evocative storytelling, Howard brought strength, purpose, and victory to the Liberal party. In this novel, Cohen takes that invocation to its absurd limit and brings the man back from the grave.

No sooner has the figure of Menzies ‘breached time’ and materialised, and the first sentence of the novel been completed (and now, on publication, held as a book in your hand), than you come to a superscripted number one. ‘Below the line’, the footnote confirms that the novel has begun. You have already been informed that the novel is about to begin by one Cordell Froat, who writes the novel’s introduction before going on to frame the work (warning Cohen that his artistic impulses might alienate his readers) within its postmodern, self-reflective, and experimental genre. Fast-track to the bibliography and find Calvino, Kundera, Nabokov, Wallace, and Sterne, authors who understood that a novel is more than just a ‘what happens next?’ story; that the novel form can, to quote Kundera, use ‘every device and every form of knowledge in order to shed light on existence’. Now add to the list, Cohen. Cohen uses fiction to test a theory: what are the ‘potential implications of Howard’s rhetorical move’?

The narrator, in twenty exegetical footnotes reflects critically on the story from a number of historical, political, and cultural angles, as well as from personal and professional ones, with insights into the genesis of the project, explorations into the writer’s fragile state of mind, musings on the ‘self-mythology’ of the difficulty of writing, and critical reflections on when and how a novel begins and ends. This works well. The audacious voice of this narrator is bewitching. ‘What the fuck are we doing down here?’ He says, ‘Get back to the story.’

‘Above the line’, again, in the story proper, the narrator is contractually committed to writing a biography of Menzies, but he is stuck: he cannot seem to write the obligatory first chapters of the man’s childhood, cannot find the ‘remarkable transformation’ that turned the child into the man, and cannot find the paths and possibilities that took that man to Canberra. This is why, when Menzies first appears, he is a full-grown man, but still only a child and not very coherent. Unable to ‘pin him down’, the biographer becomes the antibiographer, ‘a charlatan and compulsive fabricator’ persisting with the ‘foolish’ and impossible project to keep his advance and to get the thing finished. But he only has questions. If he cannot make sense of the facts, he will have to distort them and fill in the gaps. Surely that is unethical? Even Menzies gets to do some storytelling: ‘Can one begin with an anticlimax? If so, this second coming is it.’ But even he is sceptical about the genre and about these ‘microphone thrusting insisters’ and is compelled to shout over their psychological analysing and historical theorising. The anti-biographer considers whether a book of questions in lieu of the facts might be just as meritorious. But the threat of a glowering publisher and the appearance of the spectral figure motivate a new line of research. So he contacts a member of the parliamentary staff for any records of ‘ghosts, spectres and hauntings’ relating to Menzies.

Meanwhile, Menzies becomes increasingly dissatisfied with his spectral role. The unidentified J. (this narrator channels the heart and rhetorical voice of the party, and filters what can be said in public and to the public) explains that the party seeks his help, but he is only ever ‘told what to do’ and is hardly heard or seen. Thanks to the antibiographer’s inability to write him into being, poor Menzies cannot evolve into anything more than a mere symbol of the political ideas and approaches of the past. Summoned and dismissed at the will of the party, he finally has enough of it all and runs away from Canberra leaving the men behind to discover what his role was by his simply ‘no longer fulfilling it’. The more he runs away, the larger he becomes (‘I am Robert Fucking Menzies’). But nostalgic invocations of great men cannot be allowed to run wild. They are powerful and frightening things, and whether voiced by ambitious politicians or embodied by half-mortal beings in fictions, they must be contained and controlled. Thus, as the novel reaches its climactic end, everyone, antibiographer and assistant included, heads off in pursuit of the great man.

Cohen’s is a superb performance of digressions above and below the story line, of transgressions of generic rules, and of intrusions into itself and into the reader’s peace of mind. Every digression is relevant. Every transgression succeeds. Every intrusion is essential to the story and keeps you, the reader, alert to the task – and very entertained.

Comments powered by CComment