- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rediscovering Alma

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Alma Moodie’s story is remarkable, which makes it all the stranger that she has been so thoroughly forgotten. A frail child prodigy from central Queensland, she became Carl Flesch’s favourite pupil and a renowned concert violinist in Germany after World War I, friend and performer of most of the great figures of international contemporary music, from Max Reger to Igor Stravinsky. As no recordings survive, we have to guess how she played, but it was evidently a style that suited the new music of the time – crisp, rhythmic, and intense, without the overt emotionalism of an Ysaÿe or a Kreisler. She was the dedicatee of violin concerti by Hans Pfitzner and Paul Hindemith, as well as Ernst Krenek, who drew on aspects of her personality as the basis for Anita, the musician who has a brief love affair with the black jazz band leader in Jonny spielt auf, the controversial opera that made his name. Moodie’s story ends sadly with artistic and personal decline before her death in Frankfurt at forty-four, probably by her own hand. But it is the vitality, ebullience, and courage of the earlier years that leaves the strongest impression.

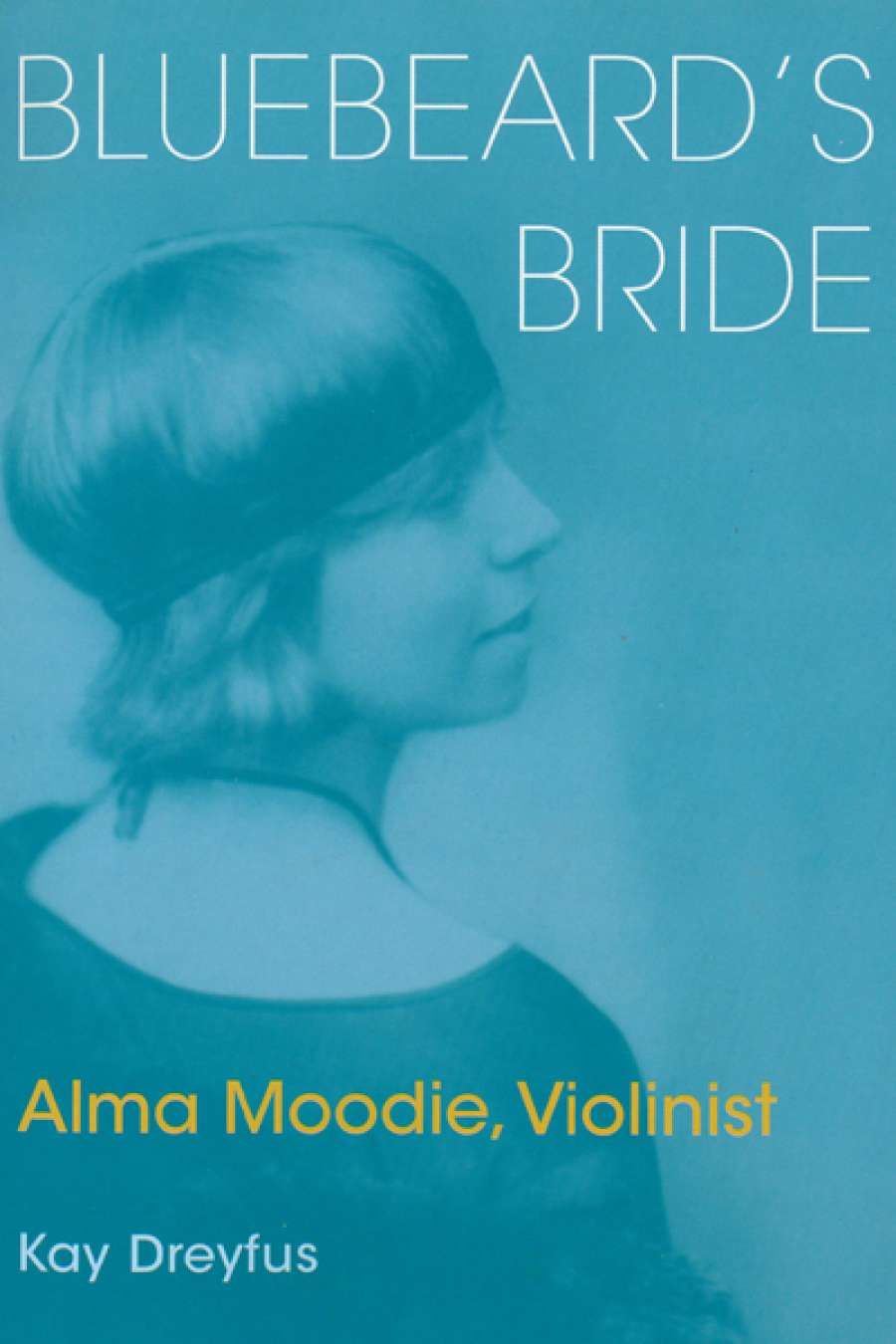

- Book 1 Title: Bluebeard's Bride

- Book 1 Subtitle: Alma Moodie, Violinist

- Book 1 Biblio: Lyrebird Press, $39.95 pb, 196 pp, 9780734037763

A Queensland gold town wasn’t the most promising place for a future great violinist to be born, but Mount Morgan was booming in 1898, and a railway had just been built linking it to Rockhampton. Five-year-old Alma, an only child, descendant of Scottish and Irish immigrants, started to make that trip regularly with her widowed mother, Susan, after she was taken on as a pupil by Louis d’Hage. Obviously, the Vienna-trained, Bohemian-born d’Hage not only knew his business but still had contacts in Europe. He helped raise the money to send Alma to study there. She and her mother arrived in 1907, just after her ninth birthday. When Alma was in her early teens, she was more or less adopted by the German composer Max Reger, the first of a series of patrons. Then came the war. Life in Germany became awkward for aliens, especially non-German speakers like Susan, so the Moodies retreated to Brussels and a few years of hardship. Reger died in 1916 and Susan, of consumption, in the spring of 1918, leaving twenty-year-old Alma alone.

Alma Moodie, c.1909–11

Alma Moodie, c.1909–11

A second patron/adoptive father came along at this point, and in October 1918 Alma went back to Germany to live in a twelfth-century castle in the Harz Mountains as ward of Fürst Christian Ernst zu Stolberg und Wernigerode, then in his fifties. In his autobiography, Krenek treated this as a sexual relationship, which may or may not have been so, but in any case it was long-lasting and affectionate, as with all Alma’s mentors and patrons.

The great violin teacher Carl Flesch was the next and, musically speaking, the most important mentor. Alma came to study with him in Berlin in 1919. Politically chaotic in the wake of Germany’s defeat, Berlin was entering an era of cultural ferment that made it the international pacesetter in the contemporary arts until the Nazis came to power in 1933. After a very successful début, Alma launched into the life of a soloist on the European circuit. She was taken up by the Swiss patron of the arts, Werner Reinhart, who was later to be guardian of her children after her death. Through him, she met most of the great figures in contemporary music – Pfitzner, Hindemith, Arthur Honegger, Stravinsky, Béla Bartók, and the young Krenek, with whom she had her first significant love affair (he later married Anna Mahler, the composer’s daughter, but only after Alma had sent him on his way). She also became friends with the young poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and after his early death played Bach at his funeral.

‘Her vitality and charm, as well as her talent for friendship, come through clearly in her lively, multilingual letters.’

According to Krenek, Alma was ‘not really attractive in the common sense of the word, perhaps not even in a more special way. But she … [was] possessed of extraordinary vitality, vivacity and of a slightly mysterious, even exotic charm …’ She doesn’t look exotic in the photographs in Dreyfus’s book, more like a young woman from small-town Australia with a direct gaze and not much dress sense, but from the perspective of Weimar Berlin that may have been exotic enough. Her vitality and charm, as well as her talent for friendship, come through clearly in her lively, multilingual letters. Of the touchy Hans Pfitzner, for example, she writes: ‘I like him and feel sorry for him in one. Il se defend, you know and is frightened of all these new things for it is so against his nature ... He is 54, has had a rotten time, his character can be rotten too, but he doesn’t want to see more than he does. On the other side he is so absolutely like his music, now & then schreit er Hurrah!’

In 1927, Alma married Alexander Balthasar Alfred Spengler, a German lawyer, with whom she had a son and a daughter. Herr Spengler is the villain in Dreyfus’s story: the Bluebeard–predator who seems to offer a safe haven but then sucks the life out of his hapless wife. But perhaps the man, of whom relatively little is known, is just a stand-in for the brutal Nazi régime that destroyed the cultural milieu Alma had made her own, sent Carl Flesch and most of her friends into exile, and left her increasingly isolated and unhappy.

The end of the story is sad. Staying in Germany was no doubt the wrong choice, both personally and in terms of posthumous reputation. But it is something to celebrate that Alma Moodie has been rediscovered in this sensitive, fair-minded biography, lavishly illustrated and beautifully produced by Lyrebird Press.

Comments powered by CComment