- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Urban legend

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Among the diaspora of European-born Jewish artists, architects, academics, and intellectuals who made a life on Australian shores pre- and post-World War II, Harry Seidler (1923–2006) was, arguably, the most successful and at various times during his life, one of the most visible and most controversial. As an architect, he left behind signature office buildings in five state capital cities, a brace of stunning modernist houses in Sydney, Canberra, and Darwin from the 1950s to the 1990s, the much-acclaimed Australian Embassy in Paris, as well as buildings in Acapulco, Hong Kong, and Vienna. He also made sure he was remembered. He published Houses, Interiors, and Projects, the first book on his work, in 1953 and then, almost without fail, every ten years a book on his architecture would appear, culminating in 1992 with the magnum opus, Harry Seidler: Four Decades of Architecture, complete with essays by architectural historians Philip Drew and Kenneth Frampton. The last word? Certainly not. Four more books followed, and now, in the tradition of marking each decade, another book has appeared on Seidler, this time by journalist and author Helen O’Neill.

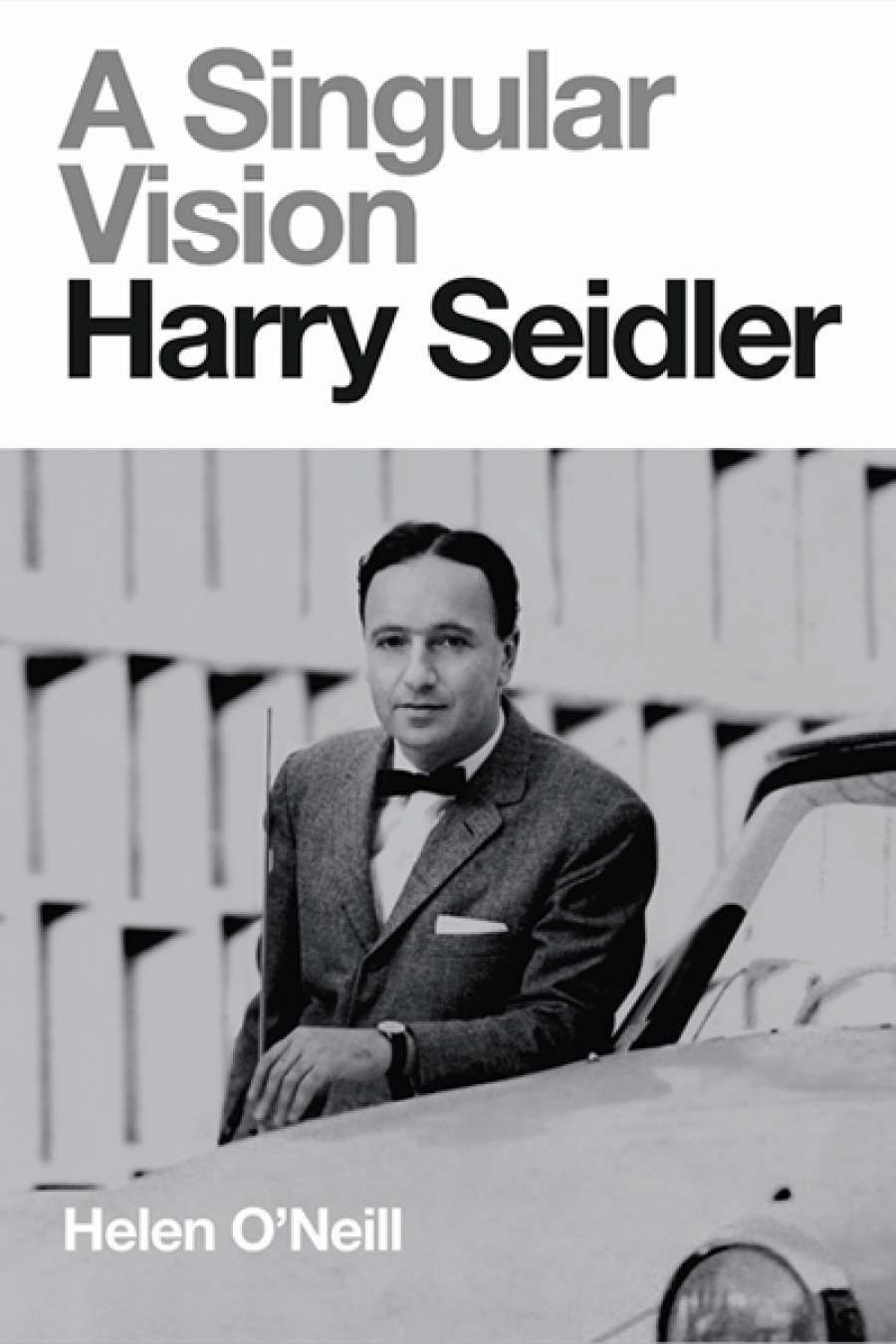

- Book 1 Title: A Singular Vision

- Book 1 Subtitle: Harry Seidler

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $49.99 hb, 380 pp, 9780732296742

A Singular Vision: Harry Seidler is different from the earlier books. Most were catalogues of assured modernist architecture, immaculately presented through photographs, drawings, and minimal text in the tradition of Swiss-French modernist architect Le Corbusier, himself an avid self-publicist. Both knew the value not just of accurately documenting one’s own work as if to cement one’s place in history, but also the value of doing so to gain more work. It was a form of professional publicity, but in the best possible taste and in the spirit of curating coherent and disciplined visual output. For Seidler, as an unknown émigré in 1950s Sydney, this was essential. Publishing was as important in the construction of reputation as was the building of buildings. No other Australian architect before or since has been so methodical or consistent in this task.

The Seidlers on their wedding day in 1958 (photograph by John Hearder)

The Seidlers on their wedding day in 1958 (photograph by John Hearder)

O’Neill’s book is also different from others on Seidler which focused largely and understandably on Seidler’s harrowing experience of being sent from Vienna to England following the Austrian Anschluss (1938) and his subsequent internment as an enemy alien not just in England but also in Canada. Seidler’s 1940–41 diaries, edited by Janis Wilton in 1986, and Alice Spigelman’s 2001 biography, written when Seidler was still alive, brought this graphically to the fore. O’Neill’s book does this too, and she speculates that these events drove much of Seidler’s deep convictions and ruthless ambition to succeed. It might also help to explain his long-held disdain for England, despite his RIBA Gold Medal in 1996, an accolade which at least one of his friends felt he should not have accepted, given his less than happy treatment by British authorities in 1940. O’Neill’s book deftly brings together these two sides of Seidler – the personal and professional – in a way that makes the book’s main protagonist more human and more flawed but at the same time, admirable and formidable in the professional battlefield that was and continues to be architectural practice.

Harry Seidler died in 2006. As a result and given his widow Penelope’s imprimatur, O’Neill has been free to expand and broaden Seidler’s already considerable publication legacy. With unparalleled access to photo albums, diaries, and personal papers, Seidler’s full life and intimate family details are revealed, and in turn complemented by photographs of his Viennese upbringing, internment in Canada with his brother Marcell, and later, many images of Seidler and his family socially at ease in Sydney, a city which he learned slowly to love and champion. We learn of Seidler’s colour blindness (surprisingly not uncommon among architects) and, ironically perhaps, his reverence and passion for collecting the colour studies of ex-Bauhaus master Josef Albers, who taught him at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1946. We learn of Seidler’s close relationship with photographer Max Dupain, who in effect became the visual biographer of Seidler’s career. Another émigré Dutchman, Dick Dusseldorp, founder of Civil and Civic (later Lend Lease) became Seidler’s most important patron and was behind the construction and financing of one of Seidler’s earliest controversial buildings, the Blues Point Tower (1957–62), the lone built fragment of a much larger Seidler vision for McMahons Point’s urban transformation. Importantly, O’Neill highlights the pivotal, and to date largely undocumented, role of Penelope Seidler. Daughter of barrister and Labor politician Clive Evatt, hence a member of one of Australia’s most significant legal–political family dynasties, Penelope married Seidler in 1958 when she was nineteen. O’Neill reveals the significance of a life partnership that until now has been largely absent from previous accounts. Penelope is described as Seidler’s avatar, and her steady hand in the Seidler practice over more than forty years points to the aptness of this metaphor. Dupain’s inclusion of Penelope in hat and Marimekko dress standing below their spectacular co-designed and newly completed house in Killara (1966–67) is a testament to the architect’s muse: a photographic tableau of architecture and life.

Penelope photographed by Dupain in 1967 at 13 Kalang Avenue in Killara (top), outside the house she and her husband designed and built.

Penelope photographed by Dupain in 1967 at 13 Kalang Avenue in Killara (top), outside the house she and her husband designed and built.

O’Neill tells openly of Seidler’s celebrated public battles with local councils, the infamous Patrick Cook cartoon (1982) depicting Seidler towers as faceless blocks and the subsequent legal case (which Seidler lost), and, perhaps most interestingly, his intellectual battle with the rise of what came to be known as postmodernism in architecture. Seidler was a vocal opponent, stridently so. His staunch public refusal to acknowledge the winds of theoretical change is perhaps one reason why younger architects began to regard Seidler’s furious pronouncements as outdated. The reality however was that Seidler’s work was not. By the mid-1970s it was already changing and becoming more urbanistically responsive, increasingly exuberant in its curvilinear forms. As might be expected of a master architect in his prime, some of Seidler’s late works, such as the Berman House (1996–99) and Brisbane’s Riparian Plaza (2000–05) are among his career best.

A Singular Vision is not an architectural monograph, and it does not set out to be. It is a biography. Yet O’Neill does capture Seidler’s internationalism, a position that aligned perfectly with Australia’s anxiety in the 1960s to be part of a global conversation politically and economically. Seidler’s internationalism, however, was drawn from his modernist education under Walter Gropius at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1945–46. Seidler, one of the only Australians to truly do so, had touched the hem of orthodox modernism as it was emerging in postwar America. As a result, Seidler counted among his colleagues not Australian architects but those he had studied under and with like Marcel Breuer and I.M. Pei. He also counted as important those in the international art world like Alexander Calder, Frank Stella, and Charles O. Perry who continued to pursue the modernist project of aesthetic abstraction at an urban scale. He wanted to work with the best engineer in the world and did – collaborating with Pier Luigi Nervi on Australia Square (1960–67), then Sydney’s tallest and the world’s tallest lightweight concrete building. In short, Seidler considered himself to be a citizen of the world. It was his unflinching commitment to these beliefs that drew the ire of those who believed instead in celebrating and nurturing home-grown talent and traditions. Seidler disagreed, and he remained frustrated with Australian cultural production for most of his life. Early on, O’Neill makes the claim that Seidler was ‘the most high-profile architect Australia has ever produced’. Some will dispute this. Australian architects such as Robin Boyd, John Andrews, and Glenn Murcutt also had, and, in the case of Murcutt, continue to have, equally significant profiles overseas. There have also been émigré architects like Karl Langer in Brisbane, Ernest Milston, and Ernest Fooks in Melbourne, whose stories are equally compelling. Yet what gives Seidler exceptional status is the worldliness of his story, the undeniable quality of his buildings, and the completeness of the records to support that story. This means that O’Neill’s words on Harry Seidler will not be the last, but they have opened the field of view. The singular vision of this important architect will live on.

Comments powered by CComment