- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Education

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Notwithstanding occasional media focus on misbehaving students or senior members, the residential colleges and halls dotted around or about most Australian university campuses keep a low profile. Their influence has undoubtedly declined since the early twentieth century, when as many as one quarter of Melbourne’s enrolled undergraduate population, and a much higher proportion of full-time students, were attached to Trinity and Janet Clarke Hall, Ormond or Queen’s. But the collegiate ideal to which all these institutions aspire, more or less, still provides a vital alternative to the regrettably prevailing view of higher education as mere vocational training – especially now, when the future viability of universities themselves is called increasingly into question.

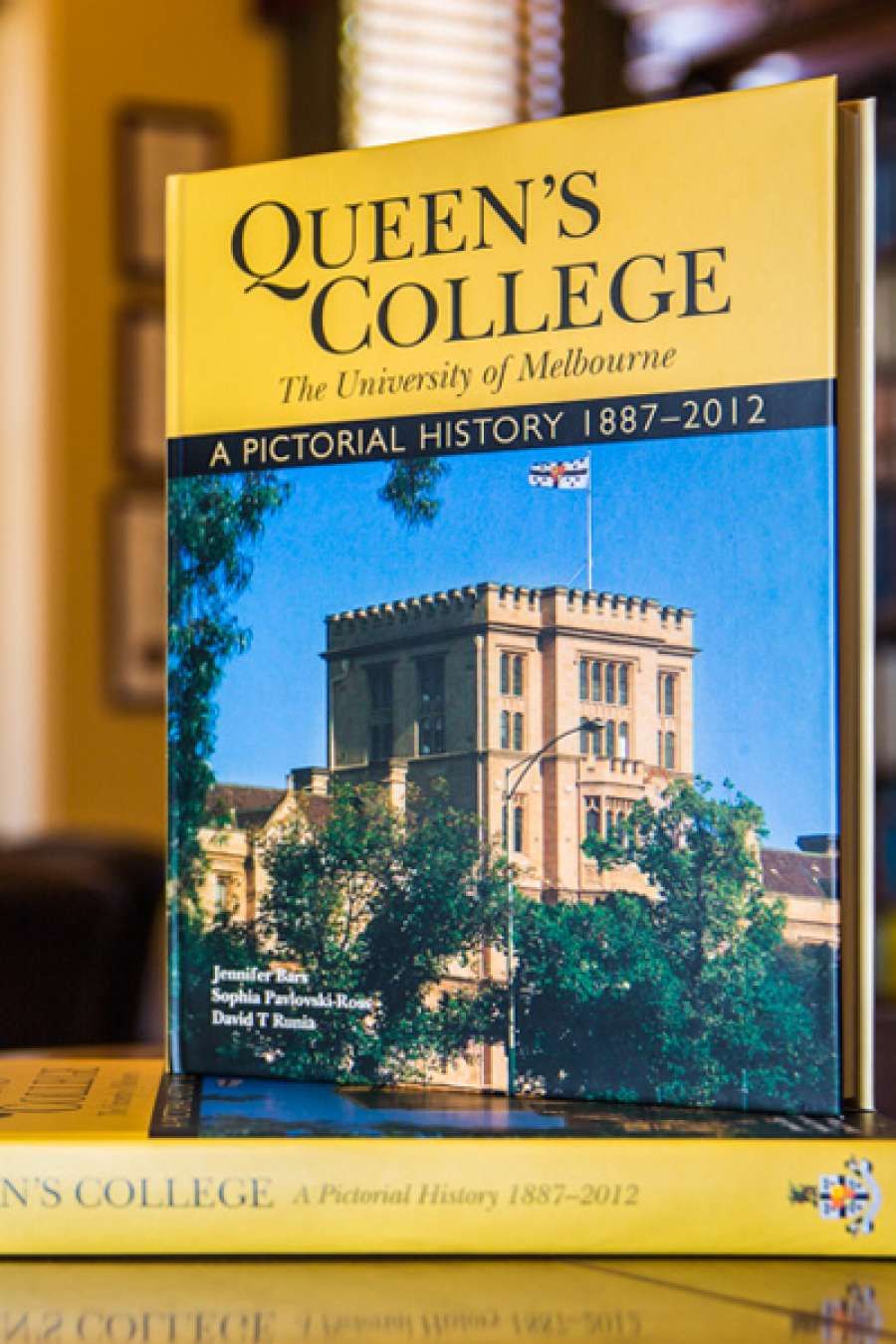

- Book 1 Title: Queen's College the University of Melbourne

- Book 1 Subtitle: A pictorial history 1887–2012

- Book 1 Biblio: Queen’s College, $70 hb, 320 pp

- Non-review Thumbnail:

That ideal, as realised at one collegiate institution over the past 125 years, could scarcely be better illustrated in every sense than by this compilation. Ten years in the making, it is anything but a standard promotional coffee table book. Shortly after relinquishing a chair in the history of philosophy at the University of Leiden to become the seventh Master of Queen’s College in 2002, David Runia (himself a keen photographer, like his predecessors Raynor Johnson and Edward Sugden) embarked upon a new and different history of the place where he had once studied. His plan was to make full use of the remarkable riches of the college’s archival collections, which include more than three thousand photographs. Unlike the accomplished centenary history by Owen Parnaby (another predecessor), illustrations would be centre stage, not mere adjuncts to the written text.

The outcome as we now have it wholly justifies the protracted labours of Runia and his two co-creators, college archivist Jennifer Bars and Sophia Pavlovski-Ross, honorary curator of historical collections. In the first place, a pictorial history must look good. This one is an absolute stunner. Its overall design, layout, typography, clarity of reproductions, and elegant cased binding could scarcely be bettered: they constitute a genuine triumph for the book’s Australian designer and printers.

Yet more than a well-presented pictorial mélange, this is a carefully thought-out presentation of college life (if not quite ‘every aspect’ thereof, pace the back-jacket blurb). Four chronological chapters trace the first century and a quarter from foundation to the present day. There follow five thematic treatments of religious, social, academic, cultural, and sporting activities, including special ‘capsules’ on such domestic arcanaas ‘waterbagging’, the college’s Wesleyana collection, and its resident goat. Drawings, engravings, and photographs of buildings, people, and objects are interspersed with reproductions of documents and miscellaneous printed ephemera: advertisements for gents’ suiting, books, and microscopes, brochures, invitations, menus, sporting and theatre programs and tickets, cuttings and extracts from the Melbourne press, and college publications, even the third-term 1969 college bill for freshman David Runia.

While visual images can have a more immediate impact than printed text, reading this diverse yet artfully assembled gallery of primary sources is not always a straightforward business, even when assisted by extensive captions. There are aspects of such an institution’s past which a pictorial history may hint at, but can scarcely capture: sex and sexuality, jokes and talk, tastes and smells, above all the complexities of human relationships, especially those cutting across generations.

Apart from its sheer attractiveness as a physical object, why should anyone unconnected with Queen’s bother with this book? Perhaps mainly for what it reveals about the college’s manifold academic, civic, and national contributions. For example: that ten of thirty ‘Wyverns’ who died on active service in World War I are listed in the chapel’s roll of honour as ‘Rev.’ speaks volumes for the prominence of the clergyman in early twentieth-century Australia. On another note entirely, the mathematical algorithm used for nearly seventy years to determine the draw of the finals series for the Victorian Football League and its AFL successor was the work of Kenneth Gordon McIntyre, a Queen’s Arts/Law student from 1928. While yet to include a Nobel laureate, former Queen’s high-flyers abound in the arts and humanities, science, economics, law, medicine, politics, and (of course) theology. These stars mostly held college scholarships; indeed the ‘poor man’s college’ (as its founding master once referred to his creation) has derived much of its continuing academic success from the able offspring of families of modest means, frequently, although far from exclusively, Methodist.

Unlike Continental Europe, or even Scotland, so central to English academic life are the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge that the early nineteenth-century radicals who founded an alternative secular institution of higher learning entitled it ‘University College London’. Across the Atlantic, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton also embodied variations on the collegiate theme; so likewise the colonial universities of Sydney and Melbourne. These latter far-flung offshoots lack the massive landed endowments which still make Oxbridge and its colleges virtually synonymous. Yet this book shows how mistaken it would be to dismiss them as mere hostels, of marginal significance either to the academic or broader community. The present challenge is indeed to extend the opportunities for an education which seeks to develop more than technical competencies, as offered by Queen’s and other such residential institutions, more widely to Australian university students in general.

Comments powered by CComment