- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1939 President Roosevelt nominated the poet Archibald MacLeish to be the Librarian of Congress, replacing Herbert Putnam, who had held the post since 1899. MacLeish had not previously been employed in a library. American librarians reacted to the news with outrage and disbelief, with one of their leaders claiming that he could no more think of a poet as the Librarian of Congress than as the chief engineer of a new Brooklyn Bridge. Roosevelt was unmoved by the protests and petitions, and MacLeish duly took up the position. He held it for less than five years, but in that time he achieved a major reorganisation of the Library, broadened its research and cultural roles, and made some astute staff appointments, including two of his successors.

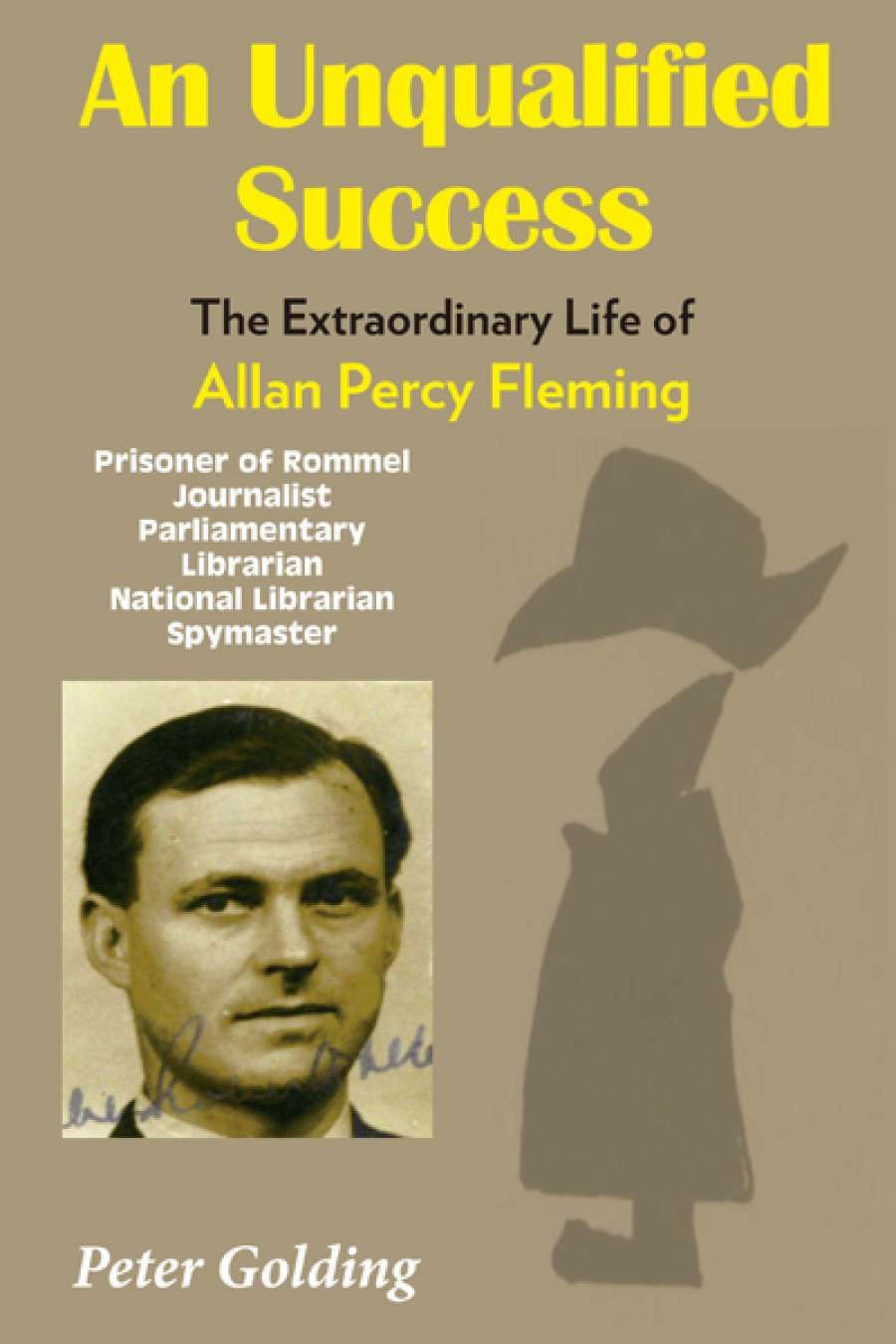

- Book 1 Title: An Unqualified Success

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary life of Allan Percy Fleming

- Book 1 Biblio: Rosenberg Publishing, $39.95 hb, 344 pp

In May 1970 a similar controversy erupted in Australia. Harold White, who had worked in the National Library since 1923, was about to retire and the prime minister announced that Allan Fleming would be the new National Librarian. Since leaving school in 1930, Fleming had been many things: a teacher, journalist, soldier, spymaster, public servant, and trade commissioner. He had also headed the Commonwealth Parliamentary Library for two years, but he did not claim to be a librarian. As he said, ‘I didn’t know a UDC from Dewey.’ His appointment to the National Library was welcomed by many of the staff, but in the wider library profession there was great resistance to the idea of a non-librarian holding the top position in Australia. A campaign by ‘concerned librarians’ caused a good deal of angst, but gradually it was accepted that the appointment was a fait accompli. Like MacLeish, Fleming stayed in the position a relatively short time, but his achievements were considerable.

Allan Fleming (1912–2001) was a natural leader. Tall, handsome, charming, and good-humoured, he quickly won the loyalty of his colleagues and the respect of the state and university librarians. He had a deep knowledge of the workings of the Commonwealth Public Service and was not afraid to challenge mandarins when they threatened the autonomy of the National Library. He had a wide range of contacts, particularly in politics, government, the defence forces, commerce, and journalism, and when necessary he used them to secure some fine collections for the Library. He made several good appointments, such as the librarian Jean Whyte and the publisher Alec Bolton. Knowing that he lacked technical expertise, Fleming did not become bogged down in administrative detail. Instead, he used his position as an interloper to pose questions and identify challenges facing the Library in the early stages of the information revolution. They included the need to broaden the collections and the range of reader services, especially in science and technology, to exploit developments in information technology, to provide leadership for Australian libraries generally, and to advise the Australian government in the field of information policy. The Government accepted a new role for the Library when it amended the National Library Act in 1973. Soon afterwards, Fleming took early retirement. His colleagues were dismayed, especially when it became apparent that his successor was quite out of his depth.

In An Unqualified Success, Peter Golding shows that head-hunters were invariably responsible for the unexpected shifts in Fleming’s career. In 1931, while editing the Melbourne student paper Farrago, Fleming was offered a position on the Argus; within a few years, he was writing leaders and feature articles for the Brisbane Courier-Mail. He served in the Army throughout World War II, rising from private to lieutenant-colonel. He fought in New Guinea, Greece, and North Africa, where he was briefly captured by German forces in November 1941. Before escaping, he had an intriguing encounter with General Rommel in which they amicably disagreed on who would win the war. After the war, Fleming returned to journalism for a time and was then nominated by Colonel Charles Spry to be director of the Joint Intelligence Bureau. For a decade he was ‘the most powerful person in Australian intelligence’. His time in the upper echelons of the Defence Department came to an end in 1958 when John Crawford invited him to be the Australian trade commissioner in Paris. Finally, it was the professional librarian Harold White, supported by various officials and politicians, who urged a reluctant Fleming to be Parliamentary Librarian and subsequently National Librarian.

Golding is a veteran journalist and the author of Black Jack McEwen: Political Gladiator (1996). Unlike McEwen, Fleming was never a household name, and many of the records of his career are locked away in official archives and are not yet open to the public. In writing the biography, Golding has been forced to rely heavily on retrospective sources: interviews with a large number of Fleming’s former colleagues and also two oral history recordings that Fleming himself made in his old age. The book contains lengthy extracts from these interviews, which tend to give a celebratory tone to the work. Apart from the opening chapter on Fleming’s rather troubled childhood, the focus is largely on his working life. Inevitably, some parts of the career are better documented than others. The wartime experiences and the Library years (1968–73) are described in much more depth than his twenty years in the Defence and Trade departments. Throughout the book, Golding explains the various institutional, political and military contexts clearly and succinctly, and he manages to keep acronyms to a minimum, even when writing about the armed forces or libraries. This is as it should be, as Allan Fleming was always scornful of those who indulged in circumlocution.

Comments powered by CComment