- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Food

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not everyone’s father sends his daughter a brace of pheasants while she is studying economics at Cambridge. With a choice of two gas rings on which to cook them, Anne Willan eviscerated and plucked the birds, then used one gas ring to cook a pheasant casserole and the other to make a caramel custard that she ‘steamed over a galvanised tin laundry bucket’. She was, I’d guess, nineteen.

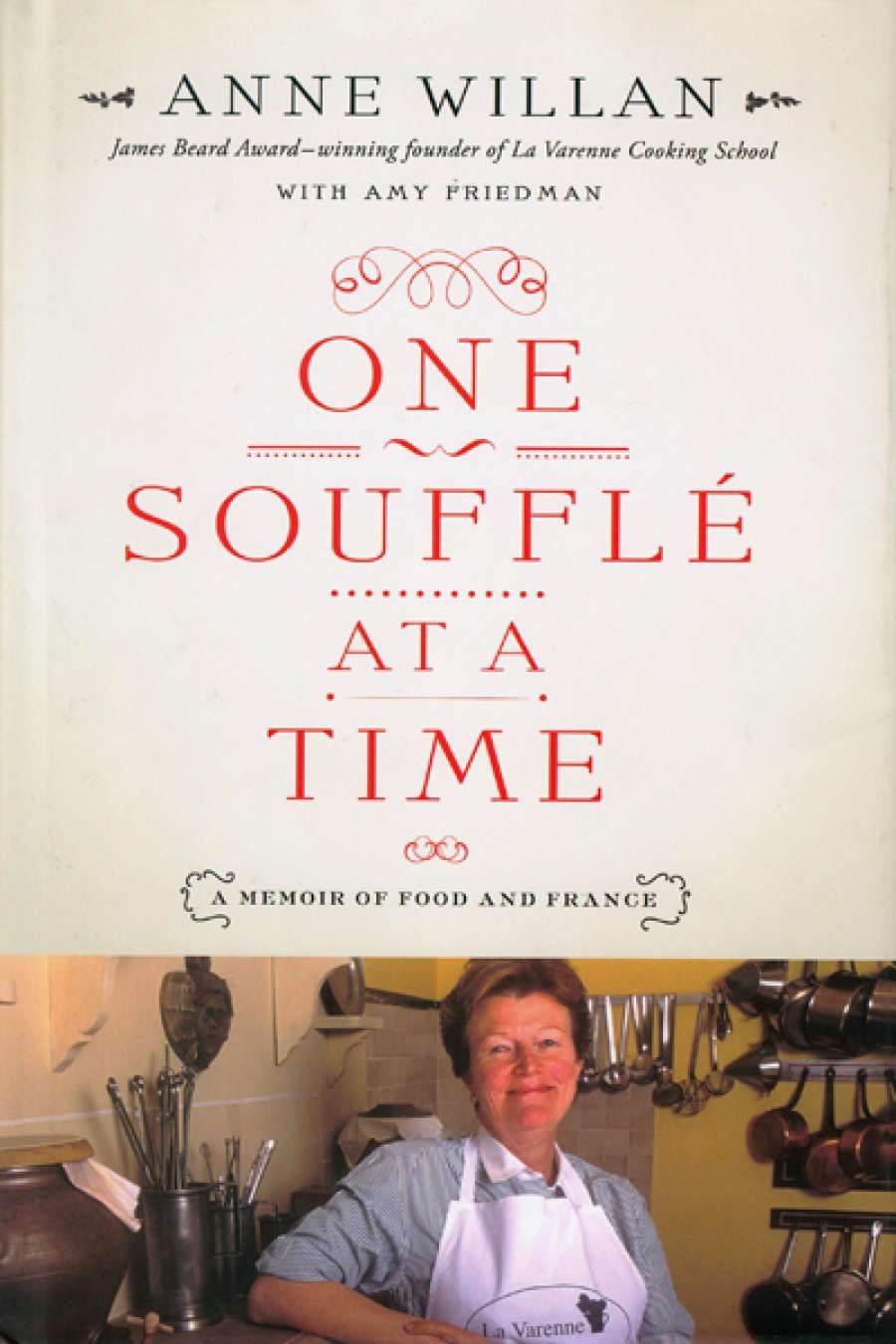

- Book 1 Title: One Soufflé at a Time

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir of food and France

- Book 1 Biblio: St Martin’s Press, US$27.99 hb, 313 pp

Willan, who was born in Yorkshire in 1938, writes that the idea of university was attractive to her because of ‘the respect and honour given to intellect, to history, to old books’. Her parents sent her to Constance Spry’s cookery and finishing school as a graduation gift. It is hard to get one’s head around the coupling of Cambridge and ‘old books’ with Constance Spry’s finishing school, but university for Willan, an only child, seems to have been a stepping stone into the kitchen.

In 1963, aged twenty-five, and now living in Paris, Willan landed a job in the household of the American society hostess Florence Van der Kemp, who lived in the Château de Versailles and was dressed by Dior (this chapter is terrific because it offers a glimpse, an almost gossipy glimpse, of a way of life we can barely imagine). We are hardly at the stepping-off point of Willan’s illustrious career, but her many strengths and assets are already clear: supportive, well-off parents (a car for her twenty-first birthday); their contacts; her own self-belief; her capacity for hard work.

Willan moved to New York in 1965. Because of fine instinct and good connections she met all the right people, cooked for Craig Claiborne, and landed a job at Gourmet magazine (answering the readers’ letters). She would later write cookery columns and then edit and transform the weekly magazine that was the Grand Diplôme Cooking Course. In the following decades, she published more than twenty cookbooks. I have one of them, and admire it: Great Cooks and Their Recipes: from Taillevent to Escoffier (1977).

In 1975 Willan opened a cooking school in Paris – École de Cuisine La Varenne. The school that brought her international fame, and it was during this period that her friendship with Julia Child grows (Paul, Julia’s husband, makes very good ‘reverse martinis’). In 1976 Time magazine deemed La Varenne perhaps ‘the hottest thing since crêpes Suzette’. Another of Willan’s abiding strengths becomes clear here: she is willing to take risks and does not try to do everything on her own. She employed a chef, not being quite one herself. She is not exactly an American in Paris, though she had become an American citizen in 1973. The test was ‘Easy Peasy’.

La Varenne was the result of Willan’s frustration with the eighty-year history of the Cordon Bleu school, a system she had been trained by. Cordon Bleu was the place for professionals from other countries to be trained in French technique. ‘I wanted to bring the best cooking in the world – French cooking – to a wider audience.’ She decided the school would be bilingual, and she was the sergeant major of printed notes.

What is the likely audience for this memoir? It is not badly written, but it is no masterpiece. It is the story of a successful career and a successful marriage, of enduring friendships and a lasting relationship with France and its cuisine. The quotations at the beginning of each chapter are literary and seem to war with Willan’s intentions, for she is, with the help of Amy Friedman, simply putting her life and career on record (the book often reads as though Willan is talking to Friedman). There is not one instance of reading literature for pleasure in the book. No inclination? No time?

Of most interest to those curious about the international history of French cooking are the parts that address the shift from the traditional cuisine of Escoffier and Pellaprat to the breath of fresh air espoused by chefs like Paul Bocuse, Michel Guérard, and others under the rubric of La Nouvelle Cuisine. Willan’s formative years, from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, were the last hurrah of classical French cuisine. She was familiar with aspic and moulds, veloutés and reductions. Many recipes are included in the book, in the appropriate places. With rare exceptions, they are extremely simple.

Sydney food writer John Newton had been assigned as Willan’s dining companion at Tetsuya’s in 1993, when she had been invited to Australia to judge the Gourmet Traveller Restaurant of the Year Award. ‘Remember when we used to import people to judge our restaurants?’ he asked when telling me this anecdote. He had apologised to Willan that he had a cold and could taste nothing. ‘That’s all right dear,’ she said cheerfully, ‘you can be my texture judge.’ He liked her very much, and so will you, in an old-fashioned kind of way. You’ll like her for her work ethic, her energy, her self-confidence, her long and happy marriage, and her love affair with France. Remember France? Remember French cuisine? Remember La Nouvelle Cuisine? Remember when it ‘reigned supreme’, as the circus master on Iron Chef cries? A world away.

Comments powered by CComment