- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

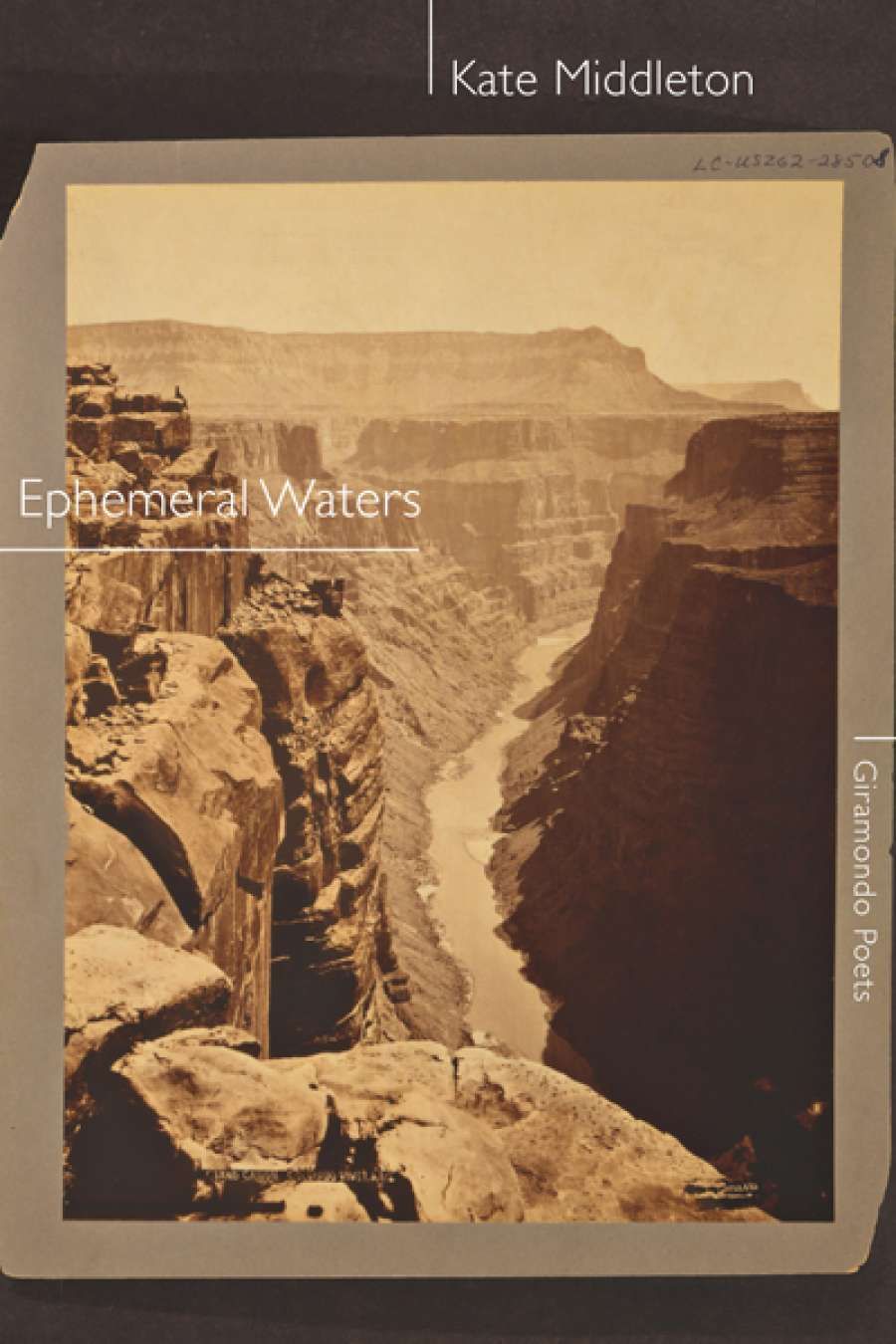

- Custom Article Title: Peter Kenneally reviews 'Ephemeral Waters' by Kate Middleton

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘As if cuffed by the ear, the Colorado river pulled me onward.’ The current that seized Kate Middleton can be felt throughout Ephemeral Waters, as she takes us from the headwaters of the Colorado, through the Grand Canyon, over the Hoover Dam, until the great river, all its water plundered along the way, expires a hundred miles from the sea. The fate that the ‘mighty Murray’ has barely avoided is accepted for the Colorado, with a few crocodile tears, because all the water stays in the United States, while the dried up ex-river is in Mexico.

- Book 1 Title: Ephemeral Waters

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 130 pp, 9781922146489

The tamed, drained Colorado is in danger north of the border, too, and it was hearing an Australian oceanographer in Washington say that the river has ‘a guillotine hanging over her at every dam, every diversion’ that made the homesick Australian want to explore it poetically, to tell its story, learn its history. ‘I found,’ she writes, ‘that the idea of this great river pushing through an arid landscape became a dream, a substitute homeland.’

Middleton flows with the Colorado across five states, and at every point exploration, myth-making, wildlife, tourists, locals, geology, and an undeclared and unpretentious psycho-geography bubble along together in a stream of verse that is sometimes silty, sometimes clear, but always unified. If Ephemeral Waters had been written in prose, it would have been a discursive, philosophical, charming doorstop, of the kind with which we are perhaps too familiar. The content, the different voices, the amount of information conveyed so lightly do give it the peregrinatory feel of a work such as W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1995), while with its sheer weight of Americana it rivals Jonathan Raban’s epic Mississippi journey in Old Glory (1981).

Thankfully, it is a book of poetry, one that clings to its subject like a rafter on a Colorado rapid. In one marvellously dramatic section, we tumble along, with John Wesley Powell’s expedition – the first to navigate the Grand Canyon – and emerge smashed but triumphant. We watch a giant condor glide through the canyon and overhear a conversation between tourists, straining to see the river from above. This kind of mélange would seem too artful in prose, but in Kate Middleton’s poetry it is effortless and natural.

Although she travelled along its whole length, she says ‘I have lived with the river much more in imagination than in reality’, and thus draws in the ideas others have had of the river, and of the West – ideas we all share, courtesy of Hollywood and of innumerable television documentaries. In John Ford’s Rio Grande, for instance, ‘the opening reel shows us horses / easing their black and white bodies / into the waters, muddy and green // of not the Rio Grande – no – / – they’re pushing their bulk / into the silt-laden, untamable Rio Colorado’.

At times, the book has very much the look and feel of other poetic explorations of American legend: Michael Ondaatje’s Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970), or Paulette Jiles’s astonishing Jesse James Poems (1988). John Wayne strides by; Charlton Heston, climbing out of his crashed rocket ship, is far from New York, in Lake Powell, on the Colorado above the Glen Canyon Dam.

Despite, or even because of, all the engineering and the thousands upon thousands of tons of concrete restraining and cajoling the river, the Colorado is fading. The massive Lake Mead, sitting behind the heroic Hoover Dam, gets lower every year. In one of the book’s most affecting sequences, the town of St Thomas (submerged by dam waters in 1938, its last stubborn inhabitant stepping from his front porch into a boat and rowing away) has re-emerged, a ghost town of foundations and vague shapes. Nearby, the bathos of Las Vegas, and the river below the dam declines into canalised utility.

There are so many names and places that it can be hard to keep track, though the book is self-annotated; with a glance at the margin we always know where we are, what nature has wrought, or if someone has spoken. The pages are so complete a landscape that to quote from them would hardly do them justice; better to just roll through them, skirting the typographical boulders and eddies. As Philip Glass says of Einstein on the Beach, the work teaches you how to read it. Wikipedia and Google maps help the reader to make sense of the scale, and one interlude, at the toxic, unnatural Salton Sea, puts the reader at the mouth of a fabulous rabbit hole that’s well worth diving into.

There is always more to find out, always another tributary to explore, but as Middleton says: ‘There are many more conversations I have not had, that I wish I could have had, and many things I have experienced, read, heard, imagined that I could not include here. No matter. This is the poem that could be written.’

No matter. So it goes. These are the poet’s refreshingly laconic judgements on the genesis of her work, and they fit in with the frontier, with the desert life all around her in bones, rocks, and people, as well as being typically Australian, if that is what you want it to be.

Comments powered by CComment