- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Jake Wilson reviews 'Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As film critics go, Geoffrey O’Brien is a lover, not a fighter: unconcerned with starting quarrels or settling scores, he simply aims to share his pleasure in what he has seen. Perhaps his remarkably good temper stems from the fact that he is not a full-time critic, but an example of that nearly extinct species, the all-round man of letters. He is editor-in-chief of the Library Of America series, and oversaw the latest edition of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations; he has published six collections of poetry, along with books on pop music, hard-boiled fiction, and the history of Times Square.

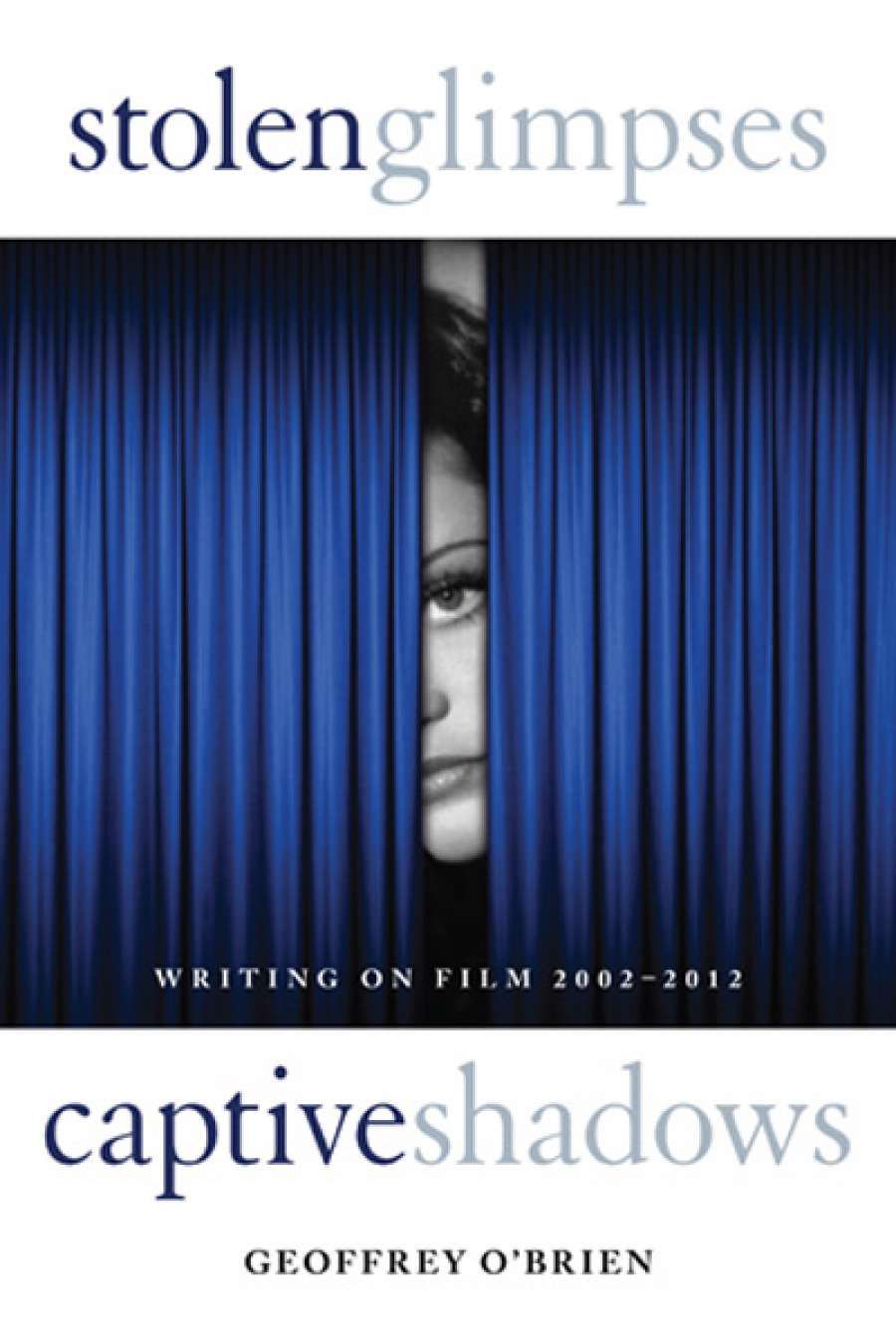

- Book 1 Title: Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writing on Film 2002–2012

- Book 1 Biblio: Counterpoint Press, $34.95 hb, 336 pp, 9781619021709

At this stage in his career, O’Brien is presumably able to choose his own subjects; of the three dozen or so essays in this very companionable new collection – all written over the last decade – the vast majority are loving tributes rather than critiques. Many of the films discussed are old favourites, like Breathless (1960) and The Lady Vanishes (1938); some are more obscure, like Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom (1966), or more recent, like Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011). There are a few broader meditations on the past and future of cinema, and a couple of excellent pieces about television: a tender account of watching Columbo in the 1970s, and an extended analysis of The Sopranos, which is the best thing I have read on that much-analysed show.

There are also assessments of two of O’Brien’s fellow critics, Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael; it is not possible to revere this pair equally, and O’Brien is firmly on Team Sarris, though characteristically generous about Kael’s strengths. Like Sarris, he belongs to the auteurist tradition which assumes that the value of a film is determined chiefly by its director. As it happens I sympathise with that viewpoint, as I do with O’Brien’s tastes in general; his over-enthusiastic discussion of Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) marks the only passage in this book where I registered strong disagreement.

A genuine polymath, O’Brien has clearly absorbed a great deal of film criticism (in French as well as English), and always knows more about the subject at hand – Japanese swordfighting sagas, medieval mystery plays – than the next critic would bother to find out. Correspondingly, his main weakness is a bookishness that can lead him to treat his subjects in an abstract, generalising way: his comments on actors, for instance, seldom offer anything really new. The wit of his writing arises less from close observation than from delight in the clash of ideas, in particular the juxtaposition of high and low culture: so the science-fiction blockbuster is seen as modern Hollywood’s answer to Jacobean tragedy, and Columbo is compared to Socrates or a Taoist monk.

This could be taken for condescending irony, but the play of allusion in O’Brien’s prose reflects a deeper interest in the ‘secret links’ between very different eras. Whether he is discussing Spiderman comics or kung fu movies or the less innocent pastiches of Steven Spielberg and Quentin Tarantino, he demonstrates a rare willingness to take popular works of art seriously – which means, among other things, understanding them as reflections of ancient rituals, conjured up in the modern temple that is the movie theatre. The word ‘ritual’ appears in more than a dozen of these essays, in reference to films that range from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) to The Passion Of The Christ (2004); the latter is described, with fascinated ambivalence, as ‘a vision of revealed religion in its savage state’.

Looking to cinema as a source of revelation, O’Brien is preoccupied with the first principles of the medium, with the ‘sheer unearthly strangeness’ of the fact this technology exists at all. Cinema is a time machine, magically letting us inspect landscapes and people that have long passed away, or a death mask, as André Bazin famously said, that reproduces the world before peeling off from it. O’Brien follows Bazin in suggesting that directorial style is finally a matter not of personal expression but of allowing things to reveal themselves, a principle that applies equally to dreamy aesthetes like Jean Cocteau and Josef von Sternberg, muscular show-offs like Akira Kurosawa and Paul Thomas Anderson, and self-effacing classicists like Eric Rohmer and Jacques Tourneur. A film is a fragment of time recovered from the dead past, as Orpheus brought Eurydice back from the underworld – though the rescue, in both cases, remains tragically incomplete.

A poet rather than a systematic theorist, O’Brien toys with these paradoxes, letting his mind drift in one direction then another. Sometimes he imagines how the barrier between film and viewer might be breached: his first encounter with Breathless, he writes, ‘was not like watching a movie of the world, but rather as if the world itself had forced its way into the movie theatre’. Elsewhere, he takes a different tack, acknowledging that cinema is all surface, and, moreover, a surface that cannot be touched. Reviewing two books on Cary Grant, he broods over inevitably disappointing scraps of biography before concluding (and who could disagree?) that the Grant who matters is the immortal star we all know. The ultimate paradox might be that cinema shows us not one unearthly world, but two: the past that remains tantalisingly out of reach, and another world that does not exist anywhere except the imagination, and never did.

Comments powered by CComment