- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

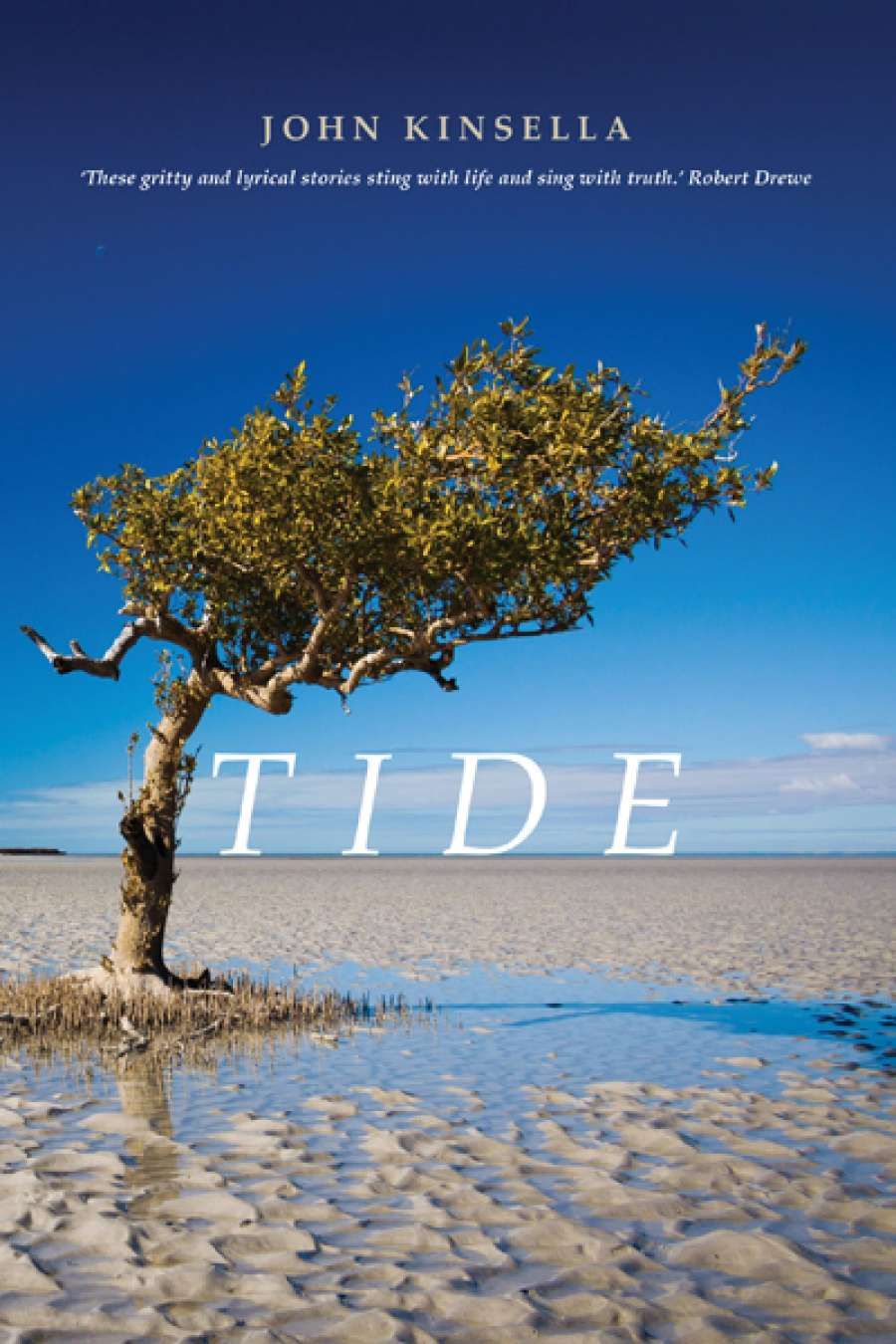

- Custom Article Title: Maria Takolander reviews John Kinsella's 'Tide'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Imagine a cross between Tim Winton’s The Turning and Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright, and you might very well imagine John Kinsella’s latest collection of fiction, Tide. Kinsella, a Western Australian like Winton, writes of the coast and of the desert, of small-town life and small-town people. However, Kinsella highlights the corruption of those landscapes and people in a way that aligns his vision more with Cook’s (which should come as no surprise, given Kinsella’s anti-pastoral poetry). There are ships pumping ‘alkaline hell’ into the waters where children swim, meatworks leaking blood to the sharks, factories, mines, old batteries, and trenches. Men are ‘brutal and brutalising’. Even boys torment and humiliate one another, often with the approval or complicity of their guardians. If someone outside Australia wanted to understand a country that hounded its first female prime minister out of office and voted in Tony Abbott on a platform against boat people and the carbon tax, this is the book I would recommend.

- Book 1 Title: Tide

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.95 pb, 237 pp, 9781921924491

Many of Kinsella’s stories evoke situations of impending danger or inevitable disaster. In the title story, we see two young boys trek out into the exposed mudflats that seem to spread all the way towards the horizon. They leave behind the ‘dark-green rigging’ of the mangroves that smelled of ‘salt and rot’, and then the tide begins to come in. In ‘Africa Reef’, a sergeant takes a group of boys out on a boat ahead of an approaching storm.

The pressure to be manly often leads these characters into danger. It is also what drives their cruelty. Characters in Kinsella’s stories are often schoolboys who are bullies, or bullied. There is no comedy or dignity in these situations. In ‘Guilt’, a schoolboy walks like a chimp to appease his tormenters, but will concede only to swinging, not flailing, his arms; showing ‘subservience and humiliation only up to a certain point’. Winton’s work is similarly interested in masculinity, but Kinsella’s is not a romantic or compensatory imagination. There is no fantastical moment of triumph and no solidarity among the weak, who can only rejoice when someone else, as described in ‘Falling’, is ‘conscripted as a victim to keep things bearable’.

Such stories of petty cruelties are set against a sublime environment of sun and wind and desert and water. This landscape is merciless, but it is also an ambiguous source of desire. Some characters are resigned to being stuck in their godforsaken towns; one refuses to even cross the Western Australian border into neighbouring states. Others want to escape to the sea or the sky: a boy dreams of launching himself in a home-made rocket in ‘Orbit’; in other stories, families head for the coast for seasonal holidays. In ‘Mesmerised’, a female narrator – one of the few in this collection – achieves a dreamy communion with the land on which she has been told her family are ‘squatters’. The story is heavily ironic. The gender of the protagonist reverses the masculine bias of traditional fantasies of colonial belonging, and the character’s experience of communion with the landscape revolves around witnessing a Muslim man in prayer on the hills behind the beach. Close by, ‘gun emplacements and a munitions dump – leftovers from the war – glowered and squatted and bristled at the ocean’, reminding us not only of the past threat of the ‘Japs’, but also of the contemporary hysteria about refugees.

There are some occasional moments of comic relief, although the milieu always remains dark. ‘Tarping the Wheat: The Wages of Sin’, a story about conformity, gives us two characters comically called Chook and Sook. Strongly reminiscent of Wake in Fright, the story shows a medical student working on a wheat belt farm and being gradually corrupted by its environment of masculine brutality, so that he ‘hated his old self and his new self’ until ‘[t]here seemed nowhere else he should be’.

Perhaps unexpectedly, and more like Winton, some of Kinsella’s stories are magical realist in nature. ‘Flight’, in which intoxicated teenagers come across a vagrant who can fly, evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s ‘A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings’. In ‘Extremities’, a misogynistic, drunken mine worker is warned off Badimia land by a ‘Nullarbor nymph’. Magical realist fiction is politically engaged literature, and the degradation of the miners in this story draws attention to their degradation of Aboriginal Australia.

As the reference to the nymph suggests, Greek myth, and particularly the story of The Odyssey, shape this collection (which is consistent with the revisionism demonstrated in Kinsella’s poetry). There is the Western Australian landscape, figured as if it is the only landscape on Earth; there is the home towards which all these characters uneasily strive; there are storms and sirens. However, there are no heroes, no gods, no happy endings. The narrator of ‘Argonaut’ tells us: ‘I have learnt that the world is an abattoir. The ocean a cauldron of blood.’

This is energetic and ruthless writing, the stunted endings of many stories paralleling the stunted lives and worlds depicted. Like the stories in The Turning, Kinsella’s collection suggests overlaps and connections, but there are none. Kinsella’s writing is stunningly good, but his vision is neither easy nor comfortable. More people will read Winton – his work provides an escape from ugliness – but we should read Kinsella if we want to address it.

Comments powered by CComment