- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Russell Marks reviews 'Trust Me: Australians and their Politicians' by Jackie Dickenson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Trust’ between voters and their elected representatives must seem rather arbitrary to politicians, whose success depends on its maintenance. Our simplistic expectations of honesty are belied by the ways in which our subconscious perceptions are herded into different narratives ...

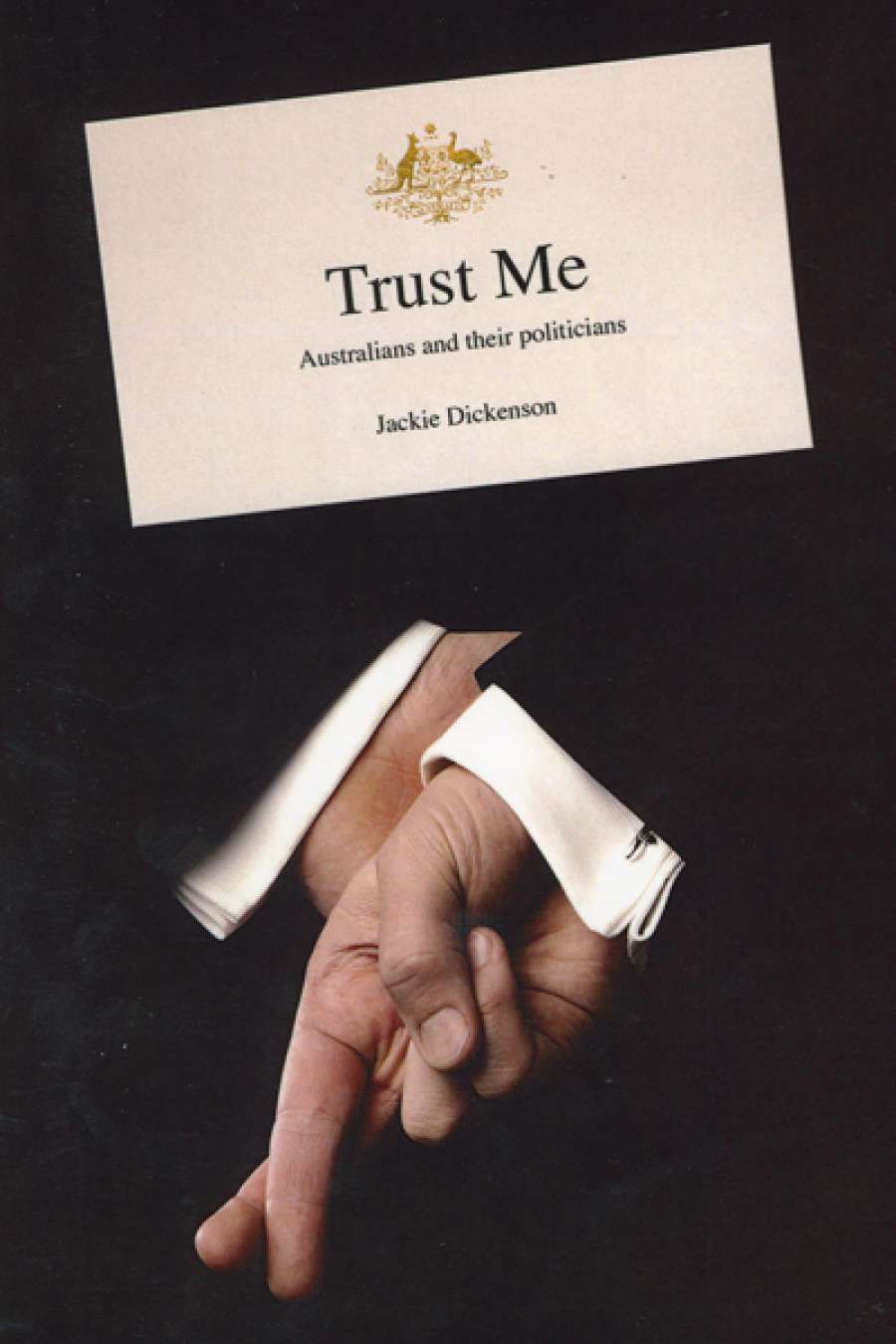

- Book 1 Title: Trust Me

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australians and their Politicians

- Book 1 Biblio: University of NSW Press, $34.99 pb, 311 pp, 9781742233819

Trust, of course, is an umbrella concept. Politicians’ perceived dishonesty is just one factor affecting the relationship between voter and parliamentarian. There are many others. What concept of representation do voters expect their politicians to embody: trusteeship or delegation? How do politicians see their role? Who is to blame for sub-standard MPs – candidates, parties, or voters? Then there are the related tensions associated with broken promises, politicians’ salaries, being a good local member as against doing the will of the party, and the role of government itself. What role does the media play? And does political trust, or the quality of parliamentarians, change over time?

In Trust Me: Australians and their Politicians, Jackie Dickenson has charted the history of the issue of trust in Australian politics from the beginnings of democracy in the 1840s to the present. Trust Me is familiar Australian political history, with a difference. It covers the main episodes: self-government; Eureka; the birth of political labour; Federation; the wars; the Depression; reconstruction and the postwar boom; the 1960s and Gough Whitlam; the 1980s and deregulation. But it does so with an emphasis on the relationship between voters and the politicians they elect.

Dickenson discusses each of the above tensions, and more, in a separate chapter within what remains a chronological history. Such presentation reflects significant editorial skill. The question of whether elected politicians are expected to exercise their own conscience as trustees of voters’ confidences, or simply to give effect to the wishes of the majority of their electors, was most pertinent to the nineteenth century, so Dickenson deals with it there. The quality of voters themselves became a hot point at every extension of the franchise – to women at the turn of the century, and when voting was made compulsory in the early 1920s. Rhetoric surrounding the broken promise had major consequences either side of the Depression, as Opposition candidates were drawn into making promises they couldn’t keep. And so on. At the end of most chapters Dickenson draws her historical observations into brief analysis of present-day issues of political trust.

Dickenson’s is not the first analysis of the voter–parliamentarian relationship. In The Emperor’s New Clothes (2002), Andrew Leigh, now a parliamentarian himself, asked why Australians don’t like their politicians. But Trust Me is the first historical account. That method has its benefits and shortcomings. A clear benefit is that we can be more discerning about contemporary commentators’ often hyperbolic claims that today’s leaders are more dishonest than yesterday’s, or that the level of trust between voters and parliamentarians has never been so low. Dickenson helpfully establishes the probability that this kind of talk is simply an extension of the discourse that has surrounded representative democracy from its mid-nineteenth-century beginnings. Democratic discourse oscillates between the criticism of politicians and criticism of voters who put them there. In more recent times, it has also incorporated criticism of media and journalists. Occasionally, voters’ hopes are temporarily restored, as many were in 2007 when Kevin Rudd allowed himself to be seen as a ‘Light on the Hill’ for those who wanted to see one; but inevitably the old discourse returns. International comparisons are outside the scope of the book, but Dickenson alludes often enough to the probability that the discourse is very similar elsewhere.

On the other hand, historical discourse analysis can lend itself to a kind of fatalism. Dickenson’s approach comes close to normalising current levels of (mis)trust as historically inevitable. The author spins this inevitability in a positive light: she suggests that criticism based on mistrust of people we don’t know personally is a healthy thing for democracy. That is true, but such a conclusion also ignores the possibility that mistrust is born of alienation from the democratic process. Even within her discursive analysis, Dickenson does not often allude to the more radical critiques of representative democracy generated by, say, socialists and ecologists, though, in her defence, such critiques have not often dominated the public conversation in Australia.

There are deeper and more structural factors at play in the historical relationship between voters and parliamentarians than Dickenson’s treatment allows. For instance, she does not refer to the issues surrounding information provision and secrecy that Wikileaks has exposed as fundamental tensions in that relationship. Nor is there any discussion of the democratic deficit produced when parties, bureaucracies, corporations, unions, and the media all adopt what Habermas, in the German context, calls ‘Deutschmark nationalism’ – the expectation that the national project is simply about ensuring that economic indicators are ‘within range’. Dickenson’s is a useful, and highly readable, introduction to a subject that begs further analysis.

Comments powered by CComment