- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Subheading: Alex Miller’s journey of the imagination

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'Coal Creek'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hanging on the cross

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The writing of a novel, Alex Miller has said, ‘is a kind of journey of the imagination in which there’s the liberty to dream your own dream … There’s always got to be a model located somewhere in fact and reality … But some of your best characters are what you think of as being purely made up, just characters that needed to be there.’

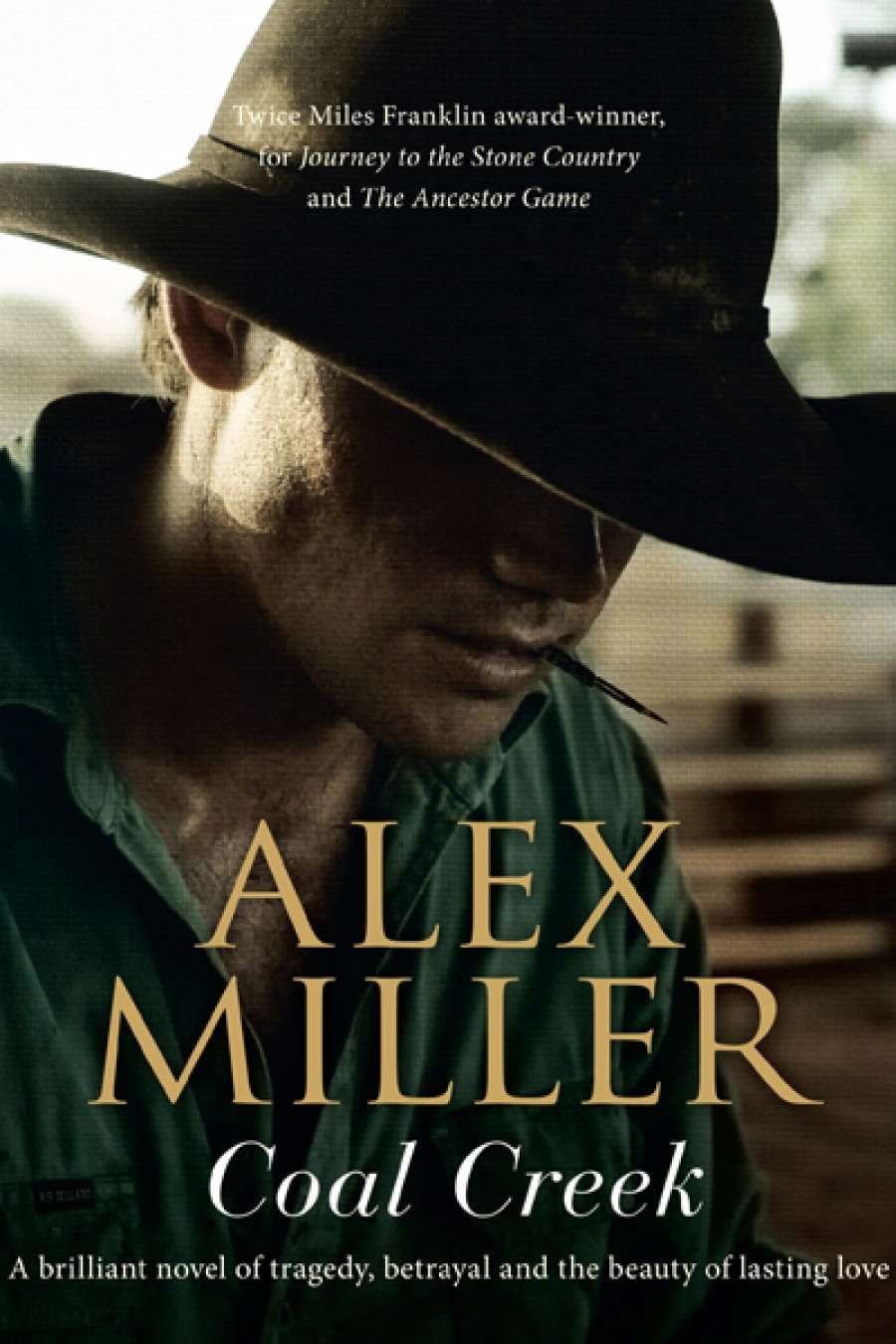

- Book 1 Title: Coal Creek

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 292 pp, 9781743316986

Bobby Blue’s story is a first-person narrative, too, but it is different. As a boy of fourteen or fifteen, he had already been mustering stray cattle in the scrub for years. He was a skilled horseman and bushman, though not as good as his father or his best friend, Ben Tobin. It is not until he is twenty that Bobby learns to read and write when he becomes the ‘offsider’ to Daniel Collins, the new local policeman in Mount Hay. And it was also when he turned twenty that, as Bobby puts it, ‘this trouble that I am giving an account of here started’.

Collins, his wife, Esme, and their daughters, Irie and Miriam, are what Bobby calls ‘coastal people’. Bobby adopts a politely disengaged, respectful attitude to Daniel and Esme, but with the twelve-year-old and fiercely independent Irie he strikes up a truly profound friendship, and it is Irie who teaches him to read and write. His ‘account’ is ungrammatical, because his speech patterns and vocabulary – unrefined and unencumbered by formal schooling – have long since been established when he meets Irie. Bobby writes more or less as he speaks, except that there is a careful deliberation about his expression which is not the writer worrying about words and rhythm but Bobby being new to words on the page, unwilling to take what he sees as risks. ‘After I started, I did not wait to be told by Daniel nothing of what needed to be done but put shoes on the police horses and took care of them without saying nothing to him. Which was the way we always worked … If we seen something needed doing we done it and no one said nothing about it.’

Far from being limited by Bobby’s fractured syntax and tightly confined narrative range, Miller maintains it with effortless consistency and turns it to brilliant advantage. Bobby’s enforced simplicity when joined to his capacity for acute observation can be wry and devastating: ‘people in Mount Hay did not know where the outback was, but Daniel and Esme seemed to be sure of knowing they was already in it … The way I saw it was that Daniel and Esme never thought too much about how it was going to be for them coming in to police a town like Mount Hay … They surely thought we was a bunch of country hicks and they knew better than we did how to do things and did not think they had nothing to learn. But they had never been out in country like the ranges before and was coastal people.’

Place is important in this novel, as the title suggests, and Bobby’s country is not for coastal people: ‘them long rolling ridges of scrub, one after another as far as the eye can see, going on into the haze of the day like a dream … Just played out mining and poor scrub country, that is all it is, fit only for them half wild cattle and that was all the good it ever was. My country. I have no other.’ Bobby’s artless demotic is stripped bare like the land he describes, and ispeculiarly moving and intense as a result.

Bobby’s attitude to and love of ‘country’ has Aboriginal echoes, and the Aborigines of the ranges are shadowy but powerfulin his story, especially Rosie, whose protest is central to the shape of the final catastrophe. ‘Them Old People,’ Bobby muses, ‘knows things us whitefellers can never know ... the knowledge is in them like the marrow of their souls. Which it will never be in us. We are like germs to them Old People, blown in on a foul wind. I knew that from Dad.’

Like Rosie, Bobby seems to see into the heart of things. He can read the signs in the scrubs, and he is a keen observer, but he does not have the Old People’s prescience. The best he can do is look back across the lineaments of a terrible tragedy in the mesh of which, at every one of its critical network of conjunctions, he comes helplessly to understand, he has been innocently entangled. His stately, unpretentious telling of it is darkened with portents, studded with reflections like ‘the bad way my life and Ben’s went …’, ‘If I had known what was going to happen between Ben and Daniel …’, ‘the trouble that come on us’.

But a crucial ingredient of the trouble is to do with place, being in this or that place and understanding what that means – its possibilities and its limitations. Without, of course, being able to foresee what disasters it would lead to, Bobby recognises early that ‘People like the Collins knew the city and the coast and they had another way of seeing things that was not our way … The Collins wanted to know what they had no need to know.’ He is tolerant of the coastal people’s incapacity to realise – not even comprehend, just realise and be calmly enrolled in – the mystery of things. ‘Daniel Collins seen understanding as the way to the comfort of his troubled soul, but anyone could have told him he was on the wrong track with that’ – a post-romantic view of the world, though Bobby would never have used such a term. On the brink of the final tragedy, however, Bobby’s tolerance of Daniel and Esme has snapped: ‘In some stupid way they seemed to me like children. I had never seen two people more in the wrong place than them two.’

By definition Bobby – shakily literate, uneducated, little read – cannot verbally place himself in any enriching, enlarging, or explanatory literary context, but Miller does it for him with exquisite tact and deftness. Bobby’s pleasure in and detailed description of ‘corned brisket and potatoes’ and ‘the yellow fat … with that bubbly look about it’ is hauntingly Dickensian, while his long meditation as he waits for the billy to boil and his love of the bush by moonlight are reminders of Lawson. There are other examples. These are not mere decoration: they extend the emotional range and intensify the growing tension with a poignancy the narrator feels but cannot articulate. ‘Words is not good for much when it comes to them feelings.’

Coal Creek is a beautifully managed novel. The almost unbearably harrowing climactic sequence – laden with the inevitability Bobby has long feared for himself, Ben Tobin, and the Collins family – is followed by a tender ‘dying fall’ in which, however, there is no mitigation of grim reality or wrenching loss. ‘We all hang on the cross, Bobby Blue,’ his mother had told him, and, in one way or another, they all do.

Comments powered by CComment