- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Lyndon Megarrity reviews 'W. Macmahon Ball' by Ai Kobayashi

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Speaking his mind

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

William Macmahon Ball (1901–86) was many things: an academic, a diplomat, a writer, and what we would now refer to as a ‘public intellectual’. As Ai Kobayashi’s new study of this fascinating man ably demonstrates, Ball was predominantly an educator. In the classroom, through books, and in the media, Ball encouraged his audience to reflect more deeply and actively on Australia’s relations with the outside world. From World War II onwards, Australia’s relationship with Asia was among his chief concerns. During his time as Professor of Political Science at Melbourne University (1949–68), Ball did much to accelerate the development of Asian studies in Australia.

- Book 1 Title: W. Macmahon Ball

- Book 1 Subtitle: Politics for the People

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 292 pp, 9781921875915

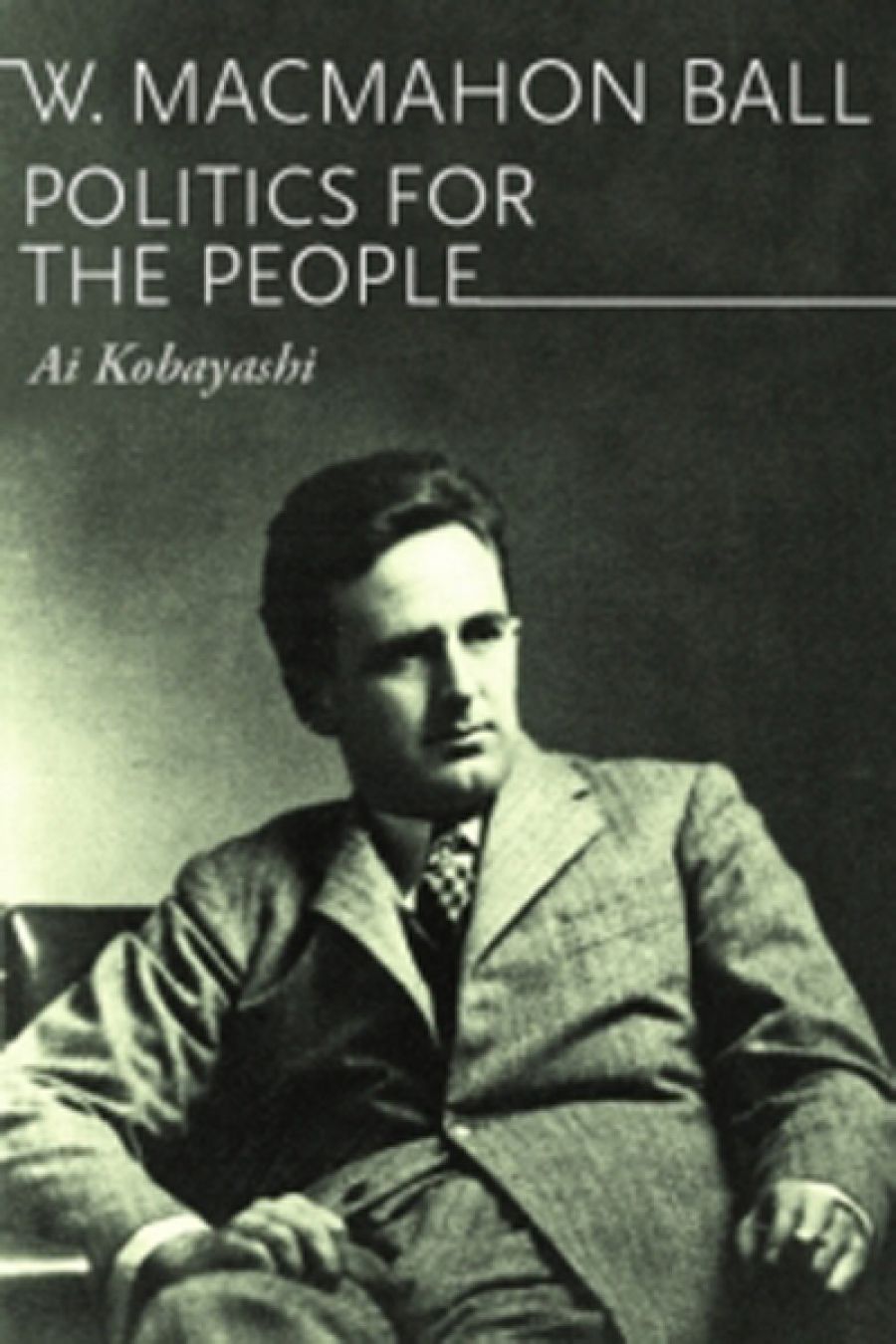

The cover of the book draws the reader in with an image of a thirty-something Ball with matinée idol looks. Small wonder that his early lectures on politics were packed and included ‘girls from Toorak who sat in the front rows and tried to catch his eye’. It is clear from the author’s account that Ball thrived on having an audience, and gained support and strength from a strong network of contacts and colleagues, especially in Melbourne.

After a shaky start, Ball proved a successful scholar at Melbourne University, where he began a long career in the 1930s as a lecturer in politics. At the same time, he developed a national profile as a commentator on world affairs in radio and in print. Ball’s armchair criticism of Australia’s lack of independent foreign policy was rudely interrupted by several life-changing events that allowed him to make a significant contribution to public life and helped give the academic a more nuanced understanding of global conflict and potential consensus.

The young academic’s visit to a German concentration camp in 1938 destroyed his belief in the validity of appeasing Hitler. A belief that force was sometimes necessary to secure human dignity was soon coupled with a sense that Australia needed to be better informed about its nearest neighbours. During the ensuing war his official duties within the Department of Information and the Australian Broadcasting Commission heightened his awareness of Asia and the relative lack of expertise available in Australia to help understand the region. Encouraging a well-informed Australian engagement with Asia subsequently became a key focus of his postwar career.

Ball’s strong interest in a more active and independent foreign policy coincided with the priorities of the Curtin–Chifley governments (1941–49). He was thus employed on several occasions between 1945 and 1948 for diplomatic missions, and was the British Commonwealth representative on the Allied Council for Japan (1946–47). Kobayashi skilfully demonstrates how profound these diplomatic experiences were for Ball, giving him practical experience in regional complexities that might have seemed straightforward in academic texts. As Ball himself wrote from pre-independence Indonesia in 1945: ‘this morning, when guns were firing in the front and back streets … the girls in their summer dresses were strolling with their boy friends and thinking only of the lovely time they were going to have together … I never realised before that peace and violence could mate so easily.’

While his diplomatic adventures proved to be useful learning experiences that enhanced his subsequent writing and teaching, Ball was often frustrated at this time by the limitations of his various official roles and his dealings with the Department of External Affairs’s brilliant but abrasive minister, H.V. Evatt. The author has provided a useful, carefully researched survey of Ball’s time as a temporary diplomat. More attention, however, might have been given to the tensions between Ball’s passion for independent foreign policy and the reality of Australia as a Middle Power caught within the new Cold War environment dominated by the United States and Russia.

The author has rightly identified this period of government-related service as a time of transition for her subject. While grateful for the experience, diplomacy was ultimately unsatisfying to Ball because he was accustomed to speaking his mind freely, whereas a diplomat must learn to trust in the benefits of the ‘softly, softly’ approach to advancing the national interest in other parts of the world. Thus Ball settled comfortably back into academia as the Foundation Professor of Political Science at Melbourne University.

While Ball’s role as a supporter and inspiration for the new generation of Asian-centred academics like Herb Feith and Jamie Mackie is appropriately acknowledged in the text, the author at times strays away from biography towards a general history of political science at Melbourne University. Readers without a deep personal connection with that institution are unlikely to find much enlightenment in the author’s discussion of academic personalities, Ball’s negotiations over staff appointments, and related departmental matters.

One of the difficulties of assessing Ball’s career as an academic is that teaching, like theatrical performance, has its greatest impact on those who were present in the room at the time. While the author’s original research amply confirms the fact that numerous distinguished former students and colleagues held W. Macmahon Ball in high regard as an educator, it is nonetheless true that ‘you had to be there’ to understand his personal touch. Fortunately, Ai Kobayashi’s biography shows that there is enough evidence in his writings to capture something of the essence of the man. Ball’s emphasis on Australia’s engagement with Asia in his later academic career was testament to his capacity to grow as an intellectual based on his personal experiences.

Comments powered by CComment