- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Colin Nettelbeck on 'Silences and Secrets' by Kay Dreyfus

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Such wide skies

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Kay Dreyfus was inspired to write about the Weintraubs Syncopators after seeing a German documentary at the Melbourne Jewish Film Festival in 2000. The film recounted the story of this interwar dance and variety band, which had earned fame in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (1930), and later used a European tour to escape from Hitler’s jazz- and Jew-hating régime. After a music-driven adventure across Russia and Asia, the group believed it had found a haven when it reached Australia in 1937, and secured a residency in Sydney’s high-society Prince’s restaurant. Then disaster struck. Accused of espionage, musicians accustomed to celebrity suddenly found themselves interned. Although they were later released, the band never reformed. Dreyfus was intrigued by the Syncopators’ story, but it was the film’s assertion of Australian responsibility for their destruction that piqued her intellectual curiosity.

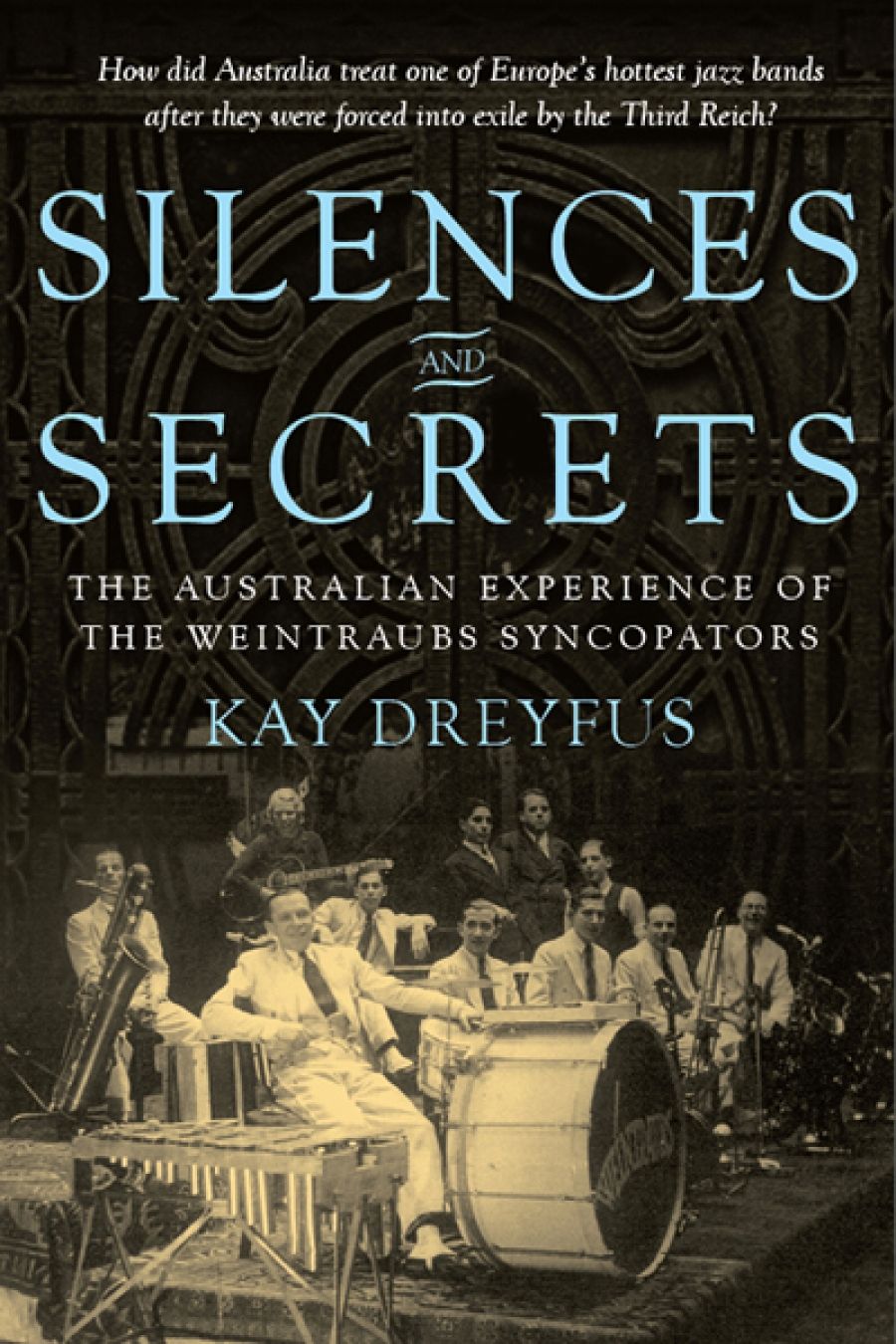

- Book 1 Title: Silences and Secrets

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australian Experience of the Weintraubs Syncopators

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.95 pb, 315 pp, 9781921867804

The result is much more than the resurrection of a colourful but largely forgotten episode in Australian musical and political history. The Weintraub case becomes a prism through which Dreyfus examines the whole socio-historical context in which the destruction of the band occurred, focusing first on the noxious conniving of the Musicians’ Union, and then on the role of the Australian state as the nation entered the intensely anxious beginnings of World War II. Each of these dimensions becomes a potent narrative in its own right, an illustration of what the author calls ‘systemic racism and generalised xenophobia’. Along the way, she also finds and produces evidence of more open and benevolent attitudes, and decisively disproves the German documentary’s insinuation that Australia’s treatment of the Weintraubs was comparable to Nazi fascism. Nonetheless, Silences and Secrets is in the end a sorry tale of endemic mean-spiritedness. It leads inexorably – despite, one feels, the author’s hope to conclude otherwise – to the pessimism of the Danielle Johnston lines cited on the last page: ‘down under / how do narrow minds / grow beneath such wide skies?’

The first major section explores how the nexus between the White Australia Policy and the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 allowed the Musicians’ Union of Australia to exercise protectionist policies and even despotic powers of exclusion in respect to non-Australian musicians, including foreign-born ones who had been naturalised. Dreyfus offers detailed analysis of the tortuous (and staggeringly idiotic) union rules, such as those that prevented instrumentalists from singing, or from playing more than one dissimilar instrument. Such constraints obviously worked against a band like the Weintraubs, whose repertoire had developed precisely around the cabaret model of variety and virtuosity on multiple instruments. Individually and as a group, they became a target for long-term MUA boss Frank Kitson, whose pursuit of them became obsessive. However, as Dreyfus demonstrates, this particular case was only one example of a deep-seated culture of prejudice and discrimination that, in the name of protecting Australian musicians, actually locked Australian music into three decades of self-imposed mediocrity.

Because of their talent and experience, the Weintraubs might just have slipped through the union snares, but there was no escaping the mechanisms Australia created to protect itself from enemy aliens. Denounced by William Buchan, a British businessman, for shady dealings during their tour of Russia, the musicians became suspect, and a number of them were interned. There was no real attempt to verify Buchan’s claims, or indeed his bona fides, which Dreyfus shows to have been extremely shaky. And then, in the Tatura I camp, Stefan Weintraub and his colleagues, who should have been considered as Jewish refugees, had to endure cohabitation with people locked up for being Nazi sympathisers. Dreyfus presents such anomalies as resulting from incompetence rather than ill will, noting Calwell’s later confession that government action on aliens was ‘largely an affair of improvisation’. She is sensitive to how much Australians remained affected by the traumas of World War I: how could authorities be expected to even try to understand that a German Jew decorated for conducting poison gas attacks on Allied soldiers in Flanders might himself become a victim of persecution in the Third Reich? She also suggests that band members may have contributed to their own difficulties by behaving arrogantly with local police officers. What is clearly true is that the very ‘foreignness’ that had constituted so much of their appeal before war broke out became a cause of immediate distrust once it did.

Silences and Secrets began life as a PhD thesis. It is impeccably researched and documented; although the text is dense, it is always eminently readable. The arguments are developed fluently, and sustain a keen critical approach to an impressive array of source materials: archives, existing scholarly work, personal testimony. The use of socio-political and psychological theory is judicious and instrumental. In its present form, it is addressed primarily to a scholarly audience, but it would be a pity to leave it there. It could readily be the basis of a more compelling film than the one that inspired it: there is mystery and intrigue; Kitson and Buchan are classic villains; there is a period-piece soundtrack; there is the evocation of the home-front at the beginning of World War II; above all, there is opportunity to probe more publicly that disturbing streak of darkness in our national ethos that seems as pertinent in the 2001 Tampa crisis and beyond as in the Tatura I internment camp all those decades earlier.

Comments powered by CComment