- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Asian Studies

- Custom Article Title: Nick Hordern reviews 'Australia’s Asia' edited by David Walker and Agnieszka Sobocinska

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Song and dance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The launch last October of the Gillard government’s White Paper Australia in the Asian Century was quite a show; in Pakistan it would have been called a tamasha – to use the lovely Urdu word for a song and dance. A flock of officials, business figures, commentators, and consultants looked grave and prophetic as they preached the importance of Asia – as if it were a new idea (their own). But as the editors of Australia’s Asia point out in their introductory chapter, ‘we have been here before’. The significance of Asia to modern Australia has been clear ever since the first ship from Bengal arrived in the infant settlement of Sydney in 1791. And it is now increasingly clear that the effects of contact with Asia on Aboriginal Australia were also considerable. While the degree of Asia’s importance may have varied, the fact of that importance is a constant.

- Book 1 Title: Australia’s Asia

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Yellow Peril to Asian Century

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $39.95 pb, 384 pp, 9781742583495

So why is the rediscovery of Asia such a regular feature of Australian life? This collection of essays includes examples of Asia awareness stretching back into the nineteenth century. And not just in the negative sense of a perceived threat – though this is a major theme – but also in the more positive veins of recognition of economic opportunities and cultural attraction.

The reader of Australia’s Asia soon comes to the conclusion that this perpetual reinvention of the wheel that characterises the recognition of Australia’s place in the region stems as much from our own domestic compulsions as it does from the external facts of geopolitical life. It tells us at least as much about the way Australians think as it does about Asia itself.

When it comes to thinking about Asia, it seems that Australians divide naturally into two camps. On the one hand are the prophets and missionaries, like those who swarmed around the White Paper launch – an Asia-aware elect striving to awaken their fellow Australians to our destiny in the region. Their audience, on the other hand, is a lay, parochial mass indifferent to the fact that their salvation lies just to their north.

If this religious terminology seems overdone, it is in fact inspired by Mads Clausen, who contributed the chapter entitled ‘Donald Horne Finds Asia’. Clausen comments: ‘The tendency to partition Australian historiography into the saved and the damned over regional engagement is patently unhelpful, yet the temptation to think in such starkly Manichean terms remains only too evident.’ In Clausen’s essay, the ‘saved’ are those writers who have emphasised engagement with Asia; the ‘damned’ those who are deemed to have given the region less than its due.

Clausen’s characterisation extends well beyond history writing; it holds good of Australian intellectual and political life in general. Particularly politics: advocacy of engagement with Asia is often accompanied by accusations of an infantile fixation on Britain, the Anglosphere, or more broadly on Europe. Support for non-European immigration and a republic naturally complements the advocacy of Asia. And while the individual components of this position may be arguable on a case-by-case basis, bundled together they become almost unquestionable, so seamless is the fit between their economic, political, geographic, and demographic logic. Asia has become the linchpin of a progressive view of Australia in the world, a perception reflected in the title of the White Paper.

This does not prevent Australia’s Asia, like any collection of works by different authors, being something of a mixed bag. The essays range from the interesting to the tendentious, the more tedious reeking of Clausen’s ‘Manichaeism’. Ipsita Sengupta’s ‘Entangled: Deakin in India’ is a postmodern case in point. It seeks to tease out the seeming paradox of how one of Australia’s founding fathers, Alfred Deakin, who served three times as prime minister in the decade after Federation, managed to be simultaneously fascinated by India – writing two books about it – and an architect of the racist White Australia immigration policy. Perhaps Deakin’s attitude is not so hard to fathom: he loved the vibrancy and beauty of India, but saw political advantage in exploiting a widespread obsession with racial purity, which he shared. But to Sengupta it’s not that simple. ‘India poses as an infinitely fluid Other to Deakin’s dream-Australia. It models the liminal beyond his cautiously defined borders of home and nation,’ she says. It became ‘[an] amniotic lair, a pet fossil of an imagined past’.

One can’t help feeling that the ‘saved’ sometimes take themselves a bit too seriously. Take the captions to the illustrations for Chengxin Pan’s essay ‘Getting Excited about China’. There is Phil May’s classic 1886 cartoon for the Bulletin, showing China as an octopus whose tentacles are labelled as social ills like ‘Opium’ and ‘Smallpox’. On the following page, the caption underneath cartoonist Ward O’Neill’s 2009 reprise of May’s image tells us that the tentacles of O’Neill’s octopus are ‘only updated accounts of Chinese vices’. But when you actually read O’Neill’s ‘updated Chinese vices’, they include ‘Teaching Kevin Rudd Mandarin’ and ‘Selling Us Flat Screen TVs’. The caption writer, fixated on a perception that Australian attitudes to China have not moved in more than a century, has missed O’Neill’s satirical point: Australia has changed – and we have a Mandarin-speaking prime minister to prove it.

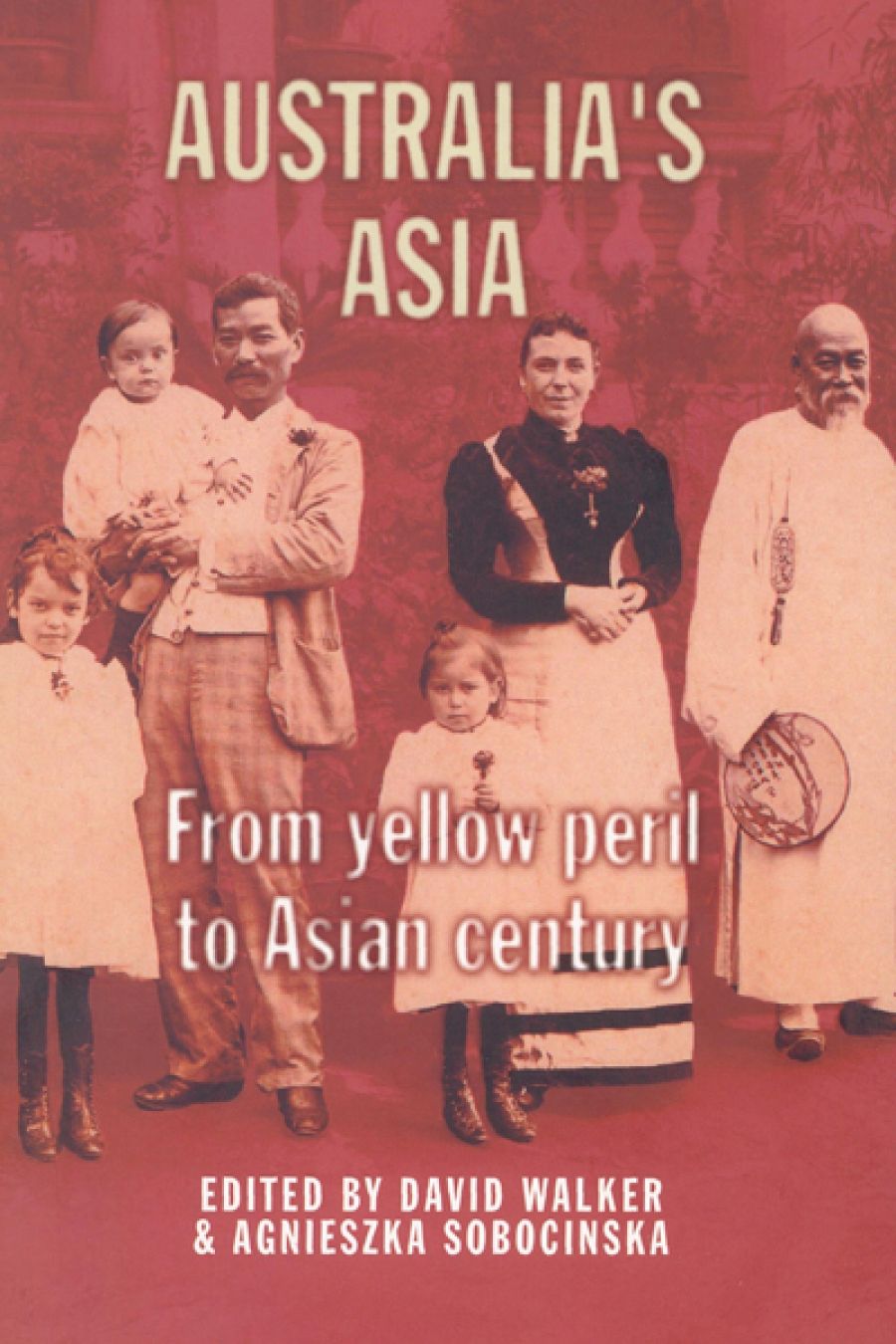

Conversely, the less polemical they are, the more interesting the chapters become. Kate Bagnall’s ‘Crossing Oceans and Cultures’ explores the lives of those European women of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who, married to Chinese men, travelled to their husband’s ancestral villages. The focus of Bagnall’s research is Margaret Tart, the Lancashire-born wife of Quong Tart, tea merchant, philanthropist, and one of the more prominent Chinese in Australia around the turn of the twentieth century. Her geographical focus is the qiaoxiang, the surprisingly small area south of the Pearl River Delta which was the homeland of so much of the nineteenth-century Chinese diaspora. Equally interesting is Mark Finnane’s description of Nationalist Chinese diplomacy in Australia in the 1930s and 1940s: it seems the Kuomintang took Australia far more seriously than Canberra took them. Then there is Shirley Jennifer Lim’s account of the 1939 visit to Australia by Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, whose career previewed the cosmopolitan allure of mixed cultures which drives so much of contemporary popular culture and fashion.

In the end, the reader is left with the impression that the debate between the saved and the damned will continue: as Australia’s Asia bears out, it has been going on a long time. This reviewer’s own introduction to the debate was Frances Letters’s The Surprising Asians, a book of youthful travels notably warm in its advocacy of the Asian perspective.

Incidentally, The Surprising Asians stands as a useful corrective to the tendency to credit the rise of Asia awareness in Australia to the Hawke and Keating governments. And not only was Letters’s book published in 1968, at a time when Australian troops were taking heavy casualties in Vietnam; it was also chosen as a set text for secondary schools by a conservative New South Wales government whose premier, when confronted with a group of anti-war protestors, had ordered his driver to ‘drive over the bastards’. As the better essays in this book show, the history of Australia’s engagement with Asia is not a simple one.

Comments powered by CComment