- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Subheading: The manhunt continues for the Prussian enigma

- Custom Article Title: Martin Thomas reviews 'Where is Dr Leichhardt?' by Darrell Lewis

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Leichhardt on the mind

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Among all the myriad characters, brilliant and brutish, fraudulent and fabulous, who lobbed into New South Wales in the mid-nineteenth century, Ludwig Leichhardt, born in rural Prussia 200 years ago, was in a class of his own.

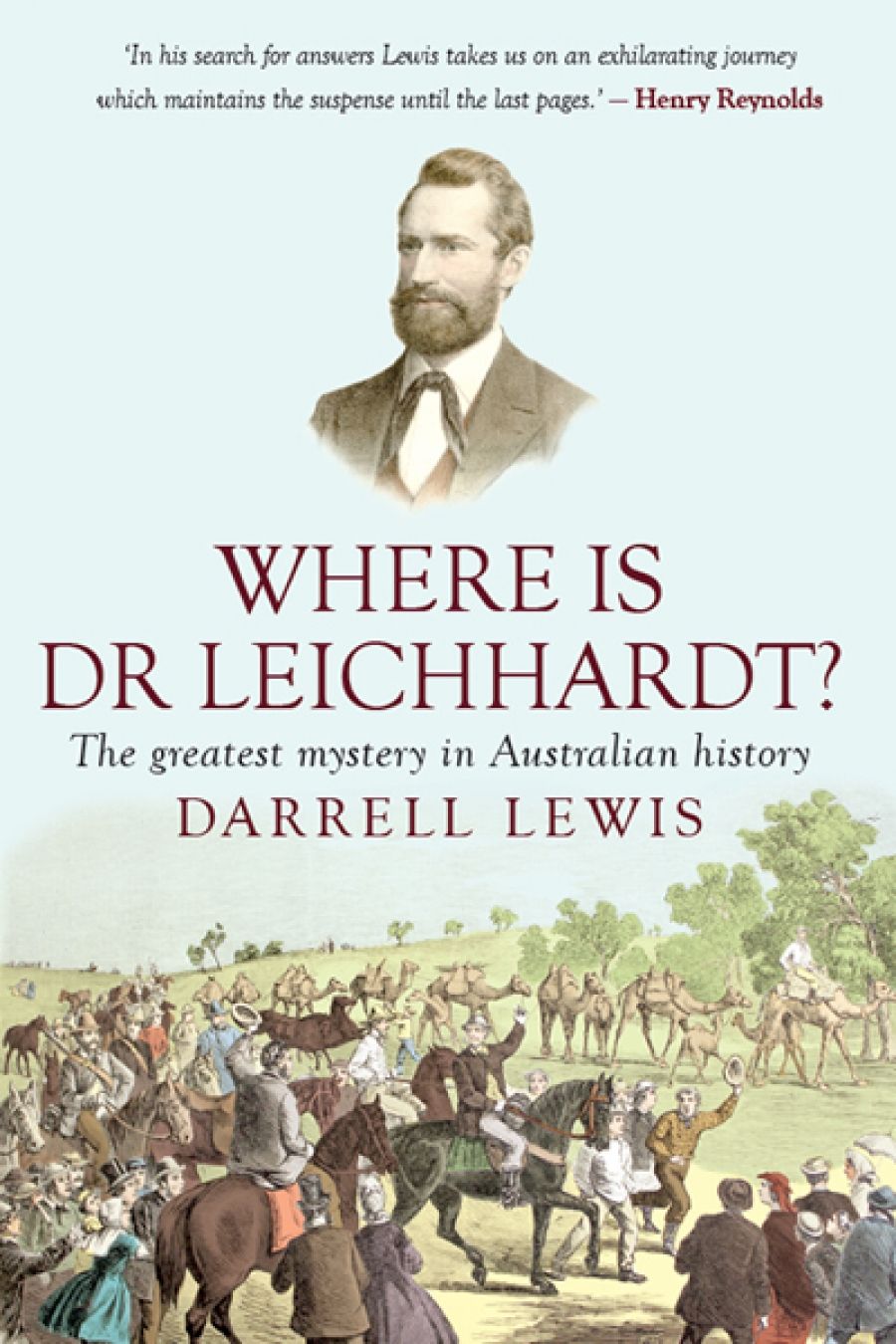

- Book 1 Title: Where is Dr Leichhardt?

- Book 1 Subtitle: The greatest mystery in Australian history

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 440 pp, 9781921867767

His father, a wood and peat vendor of modest means, made considerable sacrifices to support his brilliant son while he studied in Berlin. Ludwig read philology and became a polyglot of a high order. It was anticipated that after graduation, he would qualify for a respectable position in the civil service and repay the investment in his education. So it must have been with some alarm that Herr Leichhardt received a letter in 1836 in which his son declared that ‘[s]o long as there are things in natural science of which I am quite unaware, my studies will not be over’. A process of reinvention had begun, in which Leichhardt sought to transform himself into a new iteration of his idol, Alexander von Humboldt, explorer of Latin America and pioneer naturalist. ‘I’m setting my course myself, and shall be my own examiner,’ declared Leichhardt, in giving up formal study. ‘The bigger the building the longer it takes to build. Great structures have taken centuries, and the Strassburg minster has never been completed.’

Supported by his bosom friend William Nicholson, a well-to-do medical student from England, Leichhardt became an Anglophone and an Anglophile determined to bring glory to the British Empire. Travelling through Britain and continental Europe, he acquired the skill set – everything from mountain climbing to plant preservation – that he thought befitted a scientific adventurer. Like a character out of Conrad, he was lured by the blank spaces on maps of Australia. Financed by Nicholson, he travelled to New South Wales, determined to penetrate ‘the interior, the heart of this dark continent’.

Ludwig Leichhardt. Image courtesy NLA.

Ludwig Leichhardt. Image courtesy NLA.

Leichhardt had presented himself at the Royal Geographical Society in London. He offered to ‘spend with pleasure my unfortunately small fortune and even my life in such an expedition to which I have prepared myself these last 5 years’, but received short shrift. Sydney society, however, was receptive to this cultured European. He had no degree, yet they called him ‘doctor’. Soon he was performing medical procedures and extracting teeth. His identity as a travelling savant could flourish in this new and more fluid society where personal reinvention was more the norm than the exception.

Unable to obtain official support for an expedition, he adopted a do-it-yourself approach. Calling for volunteers and donations and appealing to the good will of colonists, he proposed a ‘squatting expedition’ – a democratic initiative that would open new country by making the first overland journey from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, the isolated military garrison on the Cobourg Peninsula in north-west Arnhem Land. He left in 1844 and got there by the seat of his pants. He sailed back to Sydney where awful verse obituarising his late self was already being recited. He attained celebrity and was lavished with reward money that capitalised another exploration. Destination: Swan River Colony, the site of Perth.

He made two attempts to get there, the second ending in the ‘greatest mystery in Australian history’, as Darrell Lewis calls it. The first attempt was merely a shambles, with the party travelling no more than 700 kilometres in eight months. They endured rain and dysentery, chased truant livestock, fought among themselves, and at last retreated. Unfazed, Leichhardt regrouped, found new recruits, and departed once more for the west. The last recorded sighting of him was near a shepherd’s hut on the Darling Downs in April 1848. He had six or seven companions, two of whom were Aboriginal. Seven horses, twenty mules, and some fifty bullocks formed the non-human contingent. While the familiar Leichhardt narrative ends here, the intriguing story unearthed by Lewis properly begins at this point.

Early in 1850, the regiment at Swan River, thinking that Leichhardt must be in the vicinity, began firing guns into the air to signal their location. This was in keeping with a long and bizarre sequence of fruitless gestures of which it was part. On the other side of the continent, when a rumour began to circulate that a party of whites had been speared in Queensland, a self-starting bushman named Gideon Lang led a tentative search party around the Maranoa River, finding not much. Things heated up in August 1850 when the Sydney Morning Herald drew attention to the colonies’ disgraceful lack of concern for the explorer. The headline of the Herald article, ‘Where is Dr. Leichhardt?’ encapsulates Lewis’s research question as well as giving him his title. He confronts ‘the greatest mystery’ with steely determination, combining Holmesian rigour with the practical-mindedness of a bush mechanic. The Leichhardt party may well have been dead by the time the first search-and-rescue brigade had packed their saddlebags, but venture out they did – and there were plenty of them. Whereas Leichhardt sought new land and scientific advancement, these were secondary explorers with a more concrete, if elusive, goal: discovering Leichhardt.

Map of Leichhardt's exploration to Port Essington (undated). John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Map of Leichhardt's exploration to Port Essington (undated). John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The book is for the most part a blow-by-blow description of these searches. Some, like A.C. Gregory, mixed searching for Leichhardt with more general exploration. Some were hardly serious, and others were seriously shambolic. Take the Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition of 1866. The Ladies of this venture prudently confined themselves to fund-raising. Gentlemen did the hard yakka up country. Crisis struck when the chaps ran out of water and was worsened by the expedition doctor who, at a crucial moment, raided the ‘medicinal’ brandy and enjoined several of his companions to join him on a bender. Lady Luck at least was with them, for they escaped with their lives.

‘In the cruel poetry of the outback, the disappearance of the searcher mirrors that of his quarry.’

Not all were so fortunate. A contingent of the Ladies’ Expedition proceeded into the Gulf country, where lives were lost. They were not alone. Fourteen known search parties have been documented, during which nine people died. The most recent person to die in search of Leichhardt was Bryce Russell, in 1937; he took twenty camels and thirty-four gallons of water into the Simpson Desert (where Leichhardt is unlikely to have gone). He was never seen again. In the cruel poetry of the outback, the disappearance of the searcher mirrors that of his quarry.

Darrell Lewis’s background is in archaeology; he has spent time in areas of Australia associated with Leichhardt. He brings to this study a bushman’s understanding and a deep, experiential knowledge of great tracts of Australia. To his credit, he has introduced an entirely new suite of material to Leichhardt scholarship, which has long been grazing on a familiar set of primary sources. A stunning array of evidence, ranging from local histories to artefacts in provincial museums, informs the investigation.

The Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition, 1865 (West Sussex Records Office)

The Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition, 1865 (West Sussex Records Office)

A shortcoming in the book is that Leichhardt himself seldom appears. One has to know some Leichhardt historiography to make much sense of it, so the book becomes unnecessarily specialised – and also somewhat lopsided. It details, as no one else has done before, the extraordinary depth of colonial Australia’s infatuation with this quixotic Prussian. Yet it is strangely indifferent to the reasons why Leichhardt, as a man and then a legend, held such sway over settler society. In fact the book is itself in the sway of this infatuation. Engrossed with the question of ‘where’, the question of why people gave their lives in search of Leichhardt is never raised.

A paucity of concrete information to guide the Leichhardt search has proven a great stimulus to the imaginations of the searchers. If one is fossicking through the bush with Leichhardt on the mind, signs can be found anywhere. Rags, rusted muskets, an aged mule, and skeletons aplenty have been claimed as talismans of the expedition. These Leichhardt ‘artefacts’, as plentiful it seems as Holy Relics of the True Cross, provide grist to the mill of Lewis in his guise of myth-busting empiricist.

The discovery of old wagon tracks spawned theories that must be false, for Leichhardt had no wagon. More promising are trees with ‘L’ inscribed upon them, for Leichhardt was known to have left such marks on his earlier expeditions. But if there is one message in this story, it is that every solution presents a further problem. In one of those irritations that history throws up to torment us, early Leichhardt searchers included a man called Landsborough who was also partial to leaving the odd arborial monogram. Was Leichhardt, Landsborough, or indeed someone else possessed of that initial, the author of the ‘L’ trees that kept turning up in northern Australia?

Tree marked by Leichhardt, Burketown (undated). Photograph taken by Alphonse Chargois, Croydon (John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Tree marked by Leichhardt, Burketown (undated). Photograph taken by Alphonse Chargois, Croydon (John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)Lewis’s excavation of the Leichhardt search is meticulous and well organised in its presentation, though often it reads more like a legal dossier than a historical narrative. The detective work has led him through a phantasmagoria of rumours, innuendoes, forged artefacts, hoax telegrams, pronouncements from a clairvoyant, and testimony from ‘witnesses’ to strange scenes in the outback. Of the latter, some were mischievous, while others were seriously deluded. Each appeal for information generated new distractions. The offer of a reward by the Bulletin for information that would finally ‘clear up’ the mystery prompted fiction as inventive as anything that appeared on the Red Page.

The direction of the narrative is predictable. The final chapter, titled ‘Discussion’, is a bushwalk through the more credible theories concerning Leichhardt’s fate, concluding with the author’s own explanation. Although credible, it is, like the others, pure supposition, and it blows something of a hollow note, given that the ‘greatest mystery’ structure creates the expectation of a resolution.

Much is revealed in this book, yet something is missed. The restricted question of where Leichhardt went, and where his bones might lie, is a narrow keyhole that provides a stilted vision of the evidential panorama uncovered. The craft of history relies on the marshalling of evidence, but interpretation is the essence of the art. The failure to find Leichhardt was in part due to the inept handling of cross-cultural challenges, for it is inevitable that Aboriginal people had information about him. It is also possible that they withheld it, having played a role in his death. Of course, stories did come from the Aboriginal side, but in the liminal and porous zone that was the colonial frontier, they morphed and transmogrified. In the black and white worlds, it seems that myths sprouted like exotic weeds. There were stories of mixed-race offspring sired by Leichhardt; rumours of a cave full of skeletons and surveying instruments; a report that Leichhardt was held prisoner in a secret desert community of blacks and white people; another of an expedition survivor living as a slave to an Aboriginal tribe.

Leichhardt's Memorial, Darwin, 1948. (Northern Territory Library)Presented with such myths, historians are often tempted to smash them to smithereens. But some of us have been arguing that such a strategy is at best reductive. Falsehoods are built on fragments of reality, and for this reason they reveal greater cultural truths. Mythology displays patterns and contours that we can map and interpret, and in the process better understand the narratives that gave meaning to colonial society as it tried to make secure its tentative foothold on foreign soil. Imperialism created the opportunity for Leichhardt’s project of self-invention to prosper. In the Australian colonies, before his death and after it, the Leichhardt narrative continued to mushroom: the composite creation of an arriving culture. This is the phenomenon that Lewis encountered in all its uncanny splendour, and it is the reason why the physical landscape, with its tantalising promise of narrative resolution in the form of a bundle of bones, can offer only so much in the search for Ludwig Leichhardt. I suspect that it is in the cultural imaginary that we will truly find him.

Leichhardt's Memorial, Darwin, 1948. (Northern Territory Library)Presented with such myths, historians are often tempted to smash them to smithereens. But some of us have been arguing that such a strategy is at best reductive. Falsehoods are built on fragments of reality, and for this reason they reveal greater cultural truths. Mythology displays patterns and contours that we can map and interpret, and in the process better understand the narratives that gave meaning to colonial society as it tried to make secure its tentative foothold on foreign soil. Imperialism created the opportunity for Leichhardt’s project of self-invention to prosper. In the Australian colonies, before his death and after it, the Leichhardt narrative continued to mushroom: the composite creation of an arriving culture. This is the phenomenon that Lewis encountered in all its uncanny splendour, and it is the reason why the physical landscape, with its tantalising promise of narrative resolution in the form of a bundle of bones, can offer only so much in the search for Ludwig Leichhardt. I suspect that it is in the cultural imaginary that we will truly find him.

Comments powered by CComment