- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Subheading: Converting a degraded saint into a typical New Englander

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews 'Hawthorne’s Habitations: A Literary Life'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The trials of St Nathaniel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Unlike Hawthorne: A Life (2003), Brenda Wineapple’s penetrating and engaging biography of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Hawthorne’s Habitations, is a work of literary criticism informed by a narrow but fascinating range of biographical details and sources. These details support Robert Milder’s construction of an author ‘divided’ by contradictory drives that remained unresolved in Hawthorne’s fiction and life.\

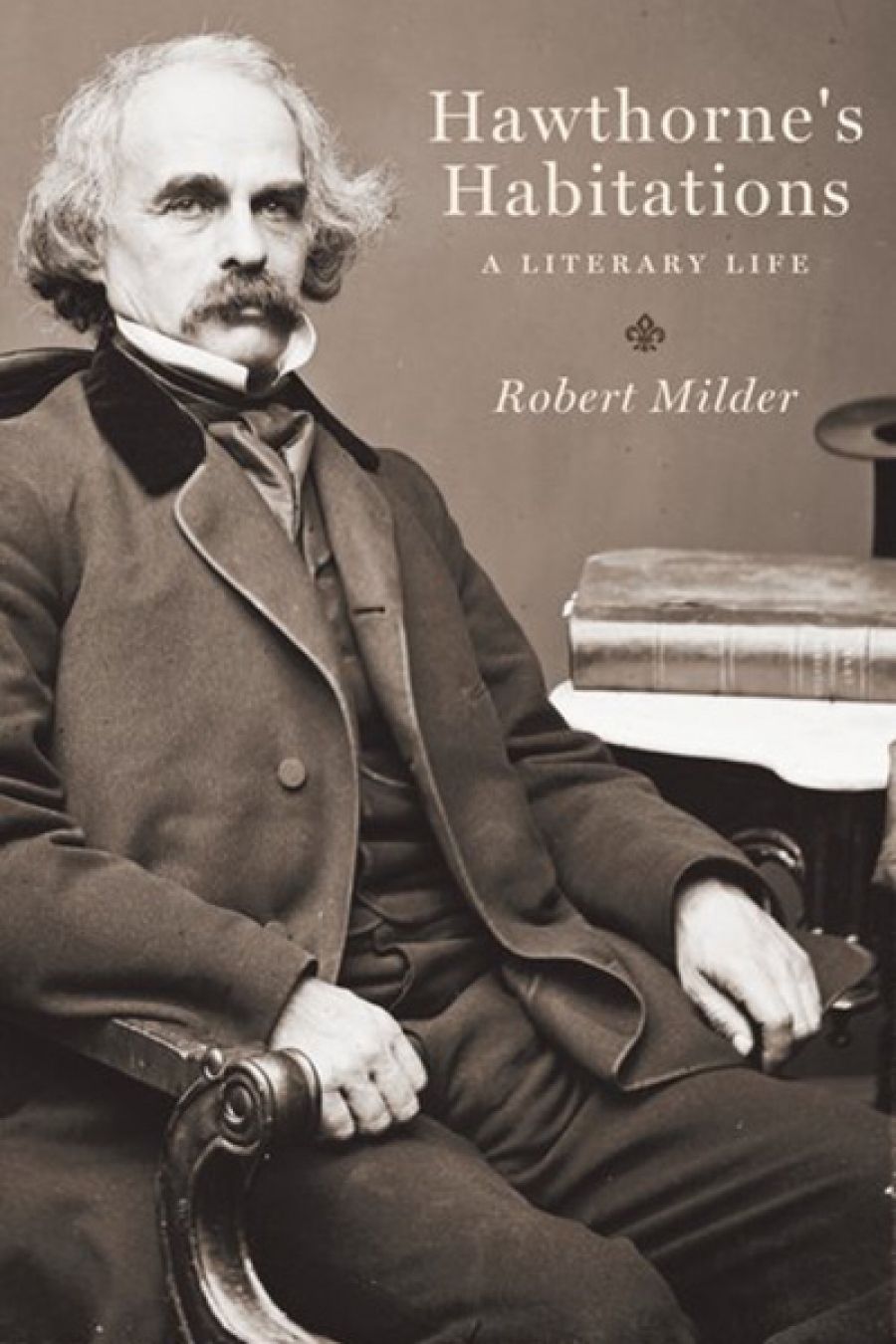

- Book 1 Title: Hawthorne’s Habitations

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Literary Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $47.95 hb, 336 pp, 9780199917259

This notion of division is prompted by Hawthorne’s major works. For instance, The Scarlet Letter (1850) lurches from a lively but subtle satire about a nineteenth-century Salem Customs House to the high-pitched turmoil of Hester and Dimmesdale’s seventeenth-century Puritan Salem. Readers are jolted from the pleasure of observing a setting through the knowing, superior eyes of a witty author into the suffocating encounter with a near-mythical Salem via the paralysing anguish of the novel’s protagonists. Such are the contradictory dimensions of all Hawthorne’s subsequent fictions, with varying degrees of accomplishment.

It is not surprising, then, that Hawthorne inspires as much annoyance as admiration in readers. In particular, those who prefer his light but piercing irony are frustrated by constant lurches into metaphysical melodrama. This frustration has as much to do with received orthodoxies as personal taste.

Twentieth-century approaches to Hawthorne varied while retaining this fundamental split in reception. The problem with any contemporary literary analysis of Hawthorne is that, like D.H. Lawrence, he has ceased to be an author and has instead become an ideological battleground. The dominant branch of Hawthorne studies in the early twentieth century was influenced by the conservative New Critics and Leavisites; it focused on close textual analysis and tended to celebrate Hawthorne’s metaphysical streak. Reacting against these conventions, subsequent approaches concentrated on textual contradictions and sought to introduce the historical and psychological Hawthorne (instead of the saint) into our understanding of his fictions. Hawthorne’s Habitations is in the tradition of the latter. Portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne by Charles Osgood, 1841 (Peabody Essex Museum)

Portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne by Charles Osgood, 1841 (Peabody Essex Museum)

There is much to admire in this inclusive study. Milder’s interpretations of the earlier short fictions are exemplary and well informed; later close readings of ‘The May-Pole of the Merry Mount’ (1836) and The Blithedale Romance (1852) are superb, and chapters dealing with Hawthorne’s years abroad represent valuable scholarship. Milder also highlights revealing distortions between the published stories about England in Our Old Home (1863) and Hawthorne’s notebook drafts of the same events.

The best and most exciting parts of Hawthorne’s Habitations emerge from contrasts between its subject and his contemporaries Henry Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Margaret Fuller. Milder provides succinct intellectual histories of the region and charts Hawthorne’s interactions with these currents; his understanding of the milieu – apparent in his previous biographies, Reimagining Thoreau (1995) and Exiled Loyalties: Melville and the Life We Imagine (2006) – is formidable and worth relishing.

Hawthorne’s ‘habitations’ are, according to Milder, Salem and Concord, in Massachusetts, where Hawthorne grew up and came into literary consciousness. These primary habitations are then mapped onto the Liverpool Hawthorne lived in from 1853 to 1857, serving as consul, and the Italy he encountered in 1858–59. As Milder explains:

‘Habitation’ also refers to a mental residence, or region of thought and sensibility rooted in time and place but not dependent on them and having its characteristic attitudes and constellation of themes, which interact with those of other times and places.

Hawthorne is therefore occupied by internal regions of thought that emerged at a particular time and place but went on to have independent existences in his mind. His habitations come to inhabit him. Usually, in Milder’s treatment, the habitations do more than ‘interact’: they wage internal battles that are then extended into Hawthorne’s fiction. Hawthorne’s divided self is, following this logic, the primary source of divisions and conflicts in his fiction.

Milder develops this further into a clear distinction between psychological and metaphysical compulsions:

The psychologist and the allegorist within Hawthorne strain against one another and contend for primacy both in representational technique and in implicit worldview, the psychologist viewing experience as an interplay of character and circumstance, the allegorist as an enactment of laws of the soul.

This is the gist of Milder’s argument: there are two Hawthornes – idealist and realist – and two narrative modes to accompany this split.

This is a common enough assertion in Hawthorne scholarship. Milder’s new idea (as far as I can tell) is that these competing drives are the product of concrete personal experiences of place; however, he too often treats the two sides of Hawthorne’s character as purely psychological constructions, and in doing so rehashes the same arguments made in several studies of Hawthorne of the last five decades. The worst strands of this critical tendency emerge from a desire to ‘uncover’ Hawthorne’s ‘secret’.

Milder notes that: ‘Philip Young has argued that the shadowy guilts in Hawthorne’s early writings are rooted in the fact of incest with his sister,’ before embracing the moderate version of this critical lunacy. He argues: ‘Physical incest seems unlikely, if only because a man of Hawthorne’s temperament would never have gotten over it. Incestuous fantasy is possible.’ Milder then asserts, without irony, that, since Hawthorne probably met ‘few eligible women’ in his youth, he likely fantasised about his sister.

In the same paragraph, Milder lurches from the idea that Hawthorne fantasised about Ebe to suggesting that Ebe also fantasised about Nathaniel. We learn that Ebe was resiliently hostile to Hawthorne’s wife, Sophia, and protective of her brother. Milder echoes, with seeming approval, Gloria Erlich’s assertion that ‘a powerful sexual motive’ underscored Ebe’s ‘possessiveness’.

While Young’s argument was a critical misstep influenced by the intellectual enthusiasms of the period (Freudianism, dismantling the canon), Milder’s substitution of Nathaniel and Ebe for characters in ‘Alice Doane’s Appeal’ (1835) inspires wonder. By contrast, his invocation of the masturbation paranoia of the period, and its potential expressions in Twice-Told Tales (1837) is more alert, but once again the assertion that Hawthorne’s sexual practices are the source of guilt and shame in his fiction is unnecessary. (Why can’t Hawthorne merely express the paranoia of his age?)

Milder subtly moves from outlining pre-existing theories about Hawthorne’s dirty secrets to speculating about possible extensions or modifications of those theories, to embracing them wholeheartedly and treating them as proven. Late in the book he asserts that Arthur Dimmesdale ‘embodied the sexual guilts of [Hawthorne’s] Salem years, compounded by who knows what subsequent imaginings’. Milder then contradicts the basis for accepting these fabrications when he notes that the symptoms of the alleged perversion (Hawthorne’s reserve, inhibitions, feelings of guilt and reclusiveness) were typical qualities of a New Englander, shared by his mother and sister:

The ‘peculiarities’ that Frederick C. Crews identifies in Hawthorne are nearly all variations on the common New England qualities; they include his ‘fear of passion; his tendency to reduce historical issues to psychomania between impulse and inhibition … his association of art with [a] guilty role; his clinical coldness, which works at cross-purposes with his endorsements of affection and community; his yearning toward ... blandness to swallow up his morbidity; and, as a result of all this, his profound loneliness and premature world-weariness.’

So, Hawthorne is Hawthorne because he is a New Englander. Better still, the solution fits Milder’s core theory about the primacy of Hawthorne’s ‘habitations’. Why, then, does he pursue the incest/masturbation theory in the first place?

The answer can be partially gleaned from Milder’s primary achievement: a reading of the latter part of Hawthorne’s life via strong reference to his notebooks and letters, successfully illuminating the complex relationship between Hawthorne’s non-fiction and fictions in the process. The result is excellent, productive scholarship grounded in tangible sources, but the biographical story goes slack through the absence of enigma and sexual intrigue.

Philip Rahv once observed that orthodox Hawthorne scholars tended to convert a lively author into a boring saint. Milder’s best work converts a degraded saint into a typical New Englander. This Hawthorne replicates the same battle between his Salem-Romantic-Puritan and Concord-Realist-Renaissance selves in each novel and story, with the former claiming victory in similarly abrupt and jarring ways each time.

The definition of a Puritan as someone who is deathly afraid that someone, somewhere, is having fun applies to Milder’s prudish and easily scandalised Hawthorne all too neatly. The shame is that what is so remarkable about Hawthorne’s fiction – the sense of social, psychological, and material entrapment; the refusal of benignly enriching resolutions (in his best work); the inescapable turmoil of being a human (impure) creature with spiritual (pure) desires – is afforded the status of a Puritan joke.

Comments powered by CComment