- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Ian Dickson on 'Wotan’s Daughter: The Life of Marjorie Lawrence'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

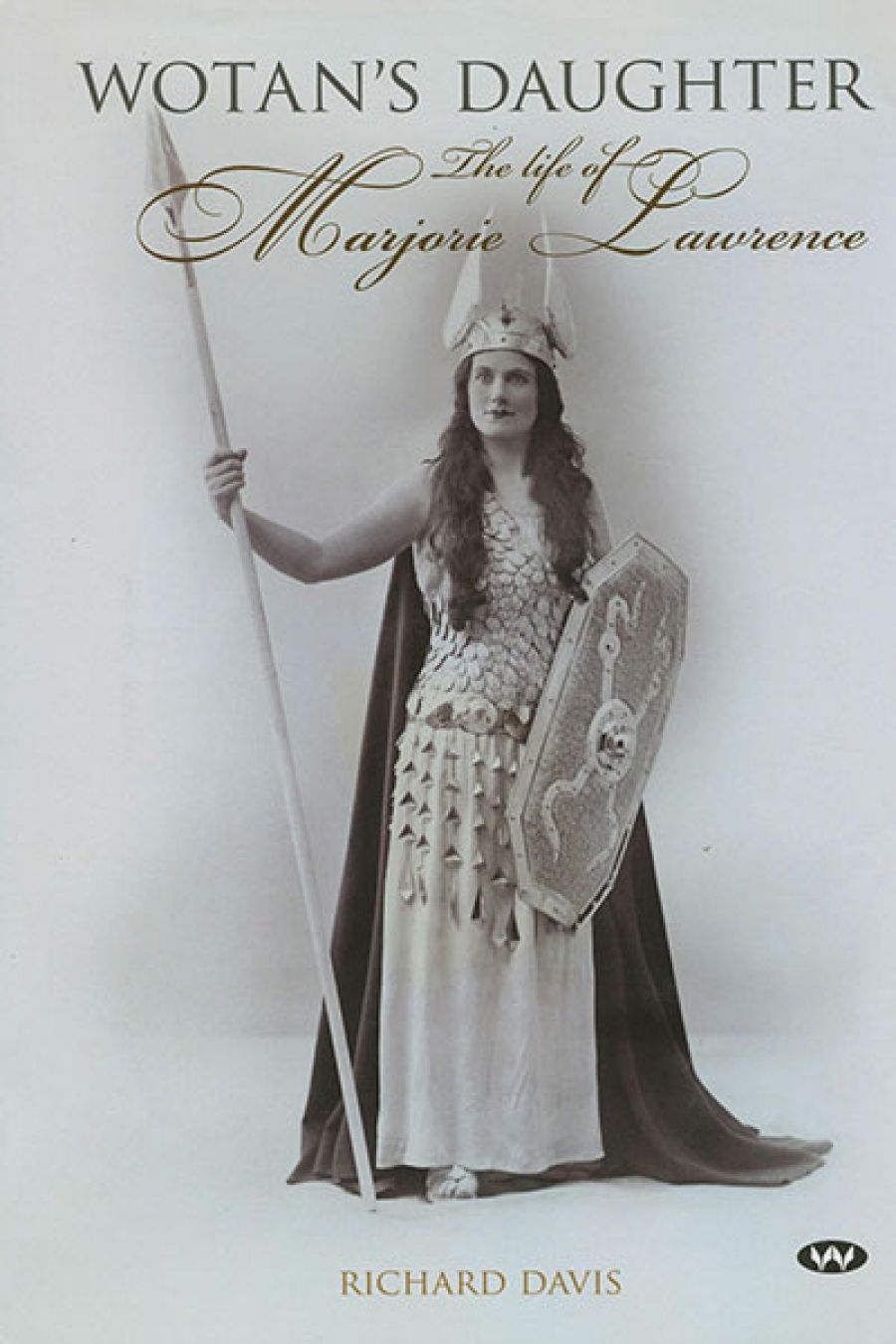

The career of Marjorie Lawrence is one of the great might-have-beens of operatic history. The saga of a young Australian woman who, in an astonishingly short period of time, became a leading singer first at the Paris Opéra and then at New York’s Metropolitan and who was poised to become the Met’s prima donna assoluta in the Wagnerian repertory when disaster struck, sounds like a script for the Hollywood weepie it eventually became. Although her career was spectacular and her talent indisputable – the renowned British critic Neville Cardus described her as ‘the finest musical artist ever to be born in Australia’ – her name seems to have faded from view. Now, in his comprehensive biography, Richard Davis redresses the balance.

- Book 1 Title: Wotan’s Daughter: The Life of Marjorie Lawrence

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $45 hb, 324 pp, 9781743051221

Marjorie Lawrence was born in 1907 to a farming family in rural Deans Marsh, Victoria. Her father, William, farmer and businessman, had a fine baritone voice and his musical abilities were passed on to his children, but it was clear to them all that Marjorie’s talent was exceptional. Against her father’s will, Marjorie and her brother Percy absconded to Melbourne, where she began her vocal training. Marjorie and William were reconciled before she sang in the 1928 Sun Aria competition in Geelong; he agreed to support her if she were to win. She won not only the Sun Aria award but all the other adult solo singing sections in the competition, and, like most Australian artists of the era, immediately made plans to travel overseas, in her case to Paris.

After intensive coaching with renowned teacher Cécile Gilly, Marjorie made a triumphant début in Monte Carlo as Elizabeth in Tannhäuser and, at the ripe age of twenty-six had an equal triumph at the Paris Opéra as Ortrud. She was now, in her twenties, singing the most demanding roles for soprano in one of the world’s leading opera houses – a mere five years after she had left Australia as a semi-trained unknown.

In some ways Marjorie was fortunate in her timing. An older generation of Wagnerian singers was fading out, and word of this young, attractive, vibrant performer soon travelled. The problem of finding first-rate Wagnerian replacements was especially dire for the Metropolitan Opera, which attempted to lure Marjorie away from Paris. Sensibly, she realised she needed more experience before facing New York’s demanding audiences and requested that they let her spend another year in Paris before joining the company. In desperation, the Met management reluctantly decided to hire a dowdy, middle-aged Norwegian soprano to fill the roles they had intended to assign to Marjorie. Thus, the international career of Kirsten Flagstad was launched.

Queen Elizabeth, Princess Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret with Marjorie Lawrence and her husband after Lawrence performed at Buckingham Palace, 1 August 1945

Queen Elizabeth, Princess Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret with Marjorie Lawrence and her husband after Lawrence performed at Buckingham Palace, 1 August 1945

When Marjorie did eventually join the Met, once again her success was instant. Famously, as Brünnhilde in a performance of Götterdämmerung three weeks after her début, she leapt on to her horse and rode him into the funeral pyre, a feat one cannot imagine many other Wagnerian divas attempting or, if they did, many horses surviving. In a 1935 live recording of Lohengrin, Marjorie is surrounded by an exceptionally starry cast, but it is she who stops the show cold with Ortrud’s invocation.

By the beginning of the 1940s, with Flagstad immured in Norway for the duration of the war, Marjorie was now the undoubted leading dramatic soprano of the Met and at the age of thirty-four could count on keeping that position for a long time. In the summer of 1941 the newly married Marjorie and her husband, Tom King, travelled to Mexico City where Marjorie was to fulfil an engagement with the recently inaugurated Mexican National Opera. During a dress rehearsal, Marjorie collapsed and was eventually taken to the American Hospital, where she was diagnosed as suffering from poliomyelitis. Davis suggests that the diagnosis may have been incorrect and that she could have had an acute reaction to the smallpox immunisation she had been required to have before she left for Mexico; but whatever the cause, she was now severely paralysed.

If her pre-paralysis career was exceptional, in many ways her post-paralysis life was even more so. With extraordinary courage and determination, she regained sufficient upper-body mobility to enable her to sing again. She sang for American and Australian troops both in hospitals and in the field and, as her strength and confidence returned, gradually took on a limited career of carefully staged opera performances and recitals, singing in America, Europe, and Australia. There is a marvellous photograph taken at Buckingham Palace in 1945 after a concert there. A seated Marjorie, every inch the regal prima donna, appears to be granting an audience to Queen Elizabeth and her two rather cowed-looking daughters.

Marjorie’s autobiography, Interrupted Melody (1949), written just after her return to the stage, became a bestseller and a successful film based very loosely on it was released in 1955. Eleanor Parker suffers bravely and lip-syncs appallingly to the voice, not of Marjorie, but of the young Eileen Farrell. Marjorie hid her dudgeon about the voice replacement and basked in the publicity.

As her singing career wound down, she began to teach and became a successful and popular mentor. One can find many warm recollections from ex-students among the comments on her YouTube recordings. Marjorie Lawrence died in 1979, at the age of seventy-two.

Richard Davis’s book is obviously a labour of love, but it is no hagiography. Most opera divas’ autobiographies are a sublime mixture of fact and fantasy, and Interrupted Melody is no exception. Davis carefully separates one from the other. Unlike many an infatuated diva biographer, Davis does not unduly denigrate Marjorie’s rivals. His clear-eyed, or rather clear-eared, comparison of the marmoreal splendour of the Flagstad voice with Marjorie’s brighter, more urgent sound is one of the book’s highlights.

Meticulously researched, highly readable, and with a comprehensive discography of this woefully under-recorded artist, Davis’s biography restores Marjorie Lawrence to her rightful place among opera’s greats.

Comments powered by CComment