- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Terzis reviews 'Loving this Planet' by Helen Caldicott and 'Waging Peace' by Anne Deveson

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Two unconventional pacifists

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In a world punctuated by civil and global conflict, it seems almost quaint to promote peace as a weapon of choice. Even in more progressive quarters, an explicit identification with pacifism seems to evoke nostalgia for a time when the enemy was obvious and the mission supposedly self-evident. But in recent decades the threat has become more nebulous, as has the relationship between defence, government, and the arms industry. Ideological differences, rather than territorial disputes, are much harder to resolve. A drone strike, regardless of its intended specificity, will always incur – to borrow from army parlance – a significant amount of ‘collateral damage’.

- Book 1 Title: Loving This Planet

- Book 1 Subtitle: Leading Thinkers Talk about How to Make a Better World

- Book 1 Biblio: New Press (Palgrave Macmillan), $24.95 pb, 382 pp, 9781595588067

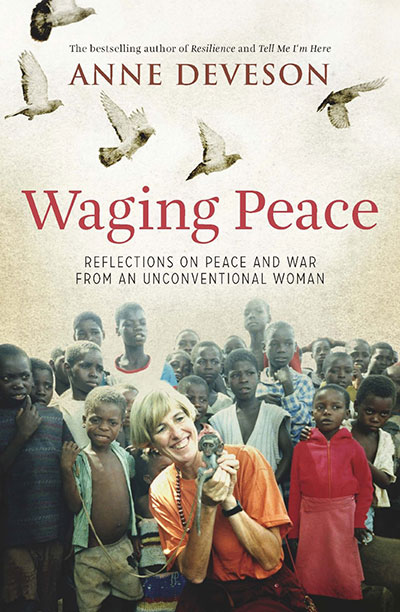

- Book 2 Title: Waging Peace

- Book 2 Subtitle: Reflections on Peace and War from an Unconventional Woman

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 248 pp, 9781743310038

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/stories/issues/352_June_2013/WagingPeace.jpg

Resistance to military intervention still exists, but it has taken the form of resignation instead of anger. Dwight Eisenhower’s famous speech on the military–industrial complex, delivered in 1961, is remarkable not only for its prescience, but also for its blunt appraisal of war as a means of conflict resolution. Among other things, he warned: ‘The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist … [A]s one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war … I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.’

The only assurance granted by the battlefield is that of agony, yet conflict continues to rage, under the banner of ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’, in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Horn of Africa. Then there is the ongoing defiance of North Korea, with its development of a nuclear program, not to mention the destabilising effects of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East.

In this context, the releases of Helen Caldicott’s Loving This Planet and Anne Deveson’s Waging Peace couldn’t be timelier. Both books, written by unconventional Australian women, provide much-needed meditation on the nature of war and our responses to it. Dr Helen Caldicott, one of the world’s most renowned anti-nuclear campaigners, has devoted three decades to the prevention of nuclear war. Her new book, Loving This Planet, voices her concerns over the nuclear arms race; her passion for climate-change action; her passion for grassroots activism; and her more mixed views on the state of contemporary politics in the United States. The structure of Loving This Planet is easy to digest, consisting of interviews Caldicott has conducted with a diverse array of big names in academia, activism, and Hollywood, including Frances Fox Piven, Antony Loewenstein, Bill McKibben, Lily Tomlin, and Martin Sheen.

There is some fascinating material to be gleaned here, especially when Caldicott is talking to experts in the field. Her interview with anthropology professor Hugh Gusterson on the sociology of bomb-making is intriguing reading, particularly the focus on birth metaphors to describe the creative process of crafting and designing a bomb, as well as the linguistic divorce from the bomb’s aftermath. People, we learn, ‘are not incinerated but carbonized’, constituting an ‘anaesthizing [of] language from which death is banished’. There are fewer revelatory insights from Caldicott’s interview with actress Lily Tomlin, which starts as an earnest discussion about The West Wing and morphs into a conversation about disappointment – in political leaders, in the system, in the watered-down progressive agenda.

Caldicott revels in her role as nuclear-free advocate, particularly in an illuminating (and disturbing) discussion with toxicology specialist Janette Sherman-Nevinger, which revolves around the far-reaching consequences of Chernobyl, decades after the event: accelerated ageing – ‘loss of mentation, heart disease, arteriosclerosis, thickening of the arteries’ – is occurring among young children, in France, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Wales, Great Britain, and so on. The conversation mostly serves to reaffirm Caldicott’s opinions on nuclear power, but Caldicott makes some salient points that highlight the absurdity of US policy-making: ‘You mustn’t have socialized medicine, but it’s all right to have socialized nuclear power and socialized nuclear weapons?’

For the most part, Caldicott is in total agreement with her interviewees – she never has to challenge their views, because she shares them. But it also means that her portrait of today’s modern world is framed in stark moralistic terms. It’s their way or the highway. There is no ambiguity about what is right and what is wrong; no sense of the complexity of overcoming these challenges, other than the fact that such triumphs are often thwarted by the negative capability of special interest politics. It would have been fascinating for Caldicott to take on her opponents – perhaps that would have given the reader an insight into the psychology of why we, as individuals and societies, conspire to act against what is in our best interests.

We get a sense of the psychological in Anne Deveson’s memoir Waging Peace, which intricately weaves in experiences from her childhood and her public life, and which gives us an insight into the woman who was influenced by them. Deveson, a documentary-maker and writer, became a commentator on social justice and equality issues, and was also part of the Royal Commission on Human Relationships. Reading about her experience with violence (growing up during World War II in Britain, seeing tiny gas masks and thinking: ‘But who would want to gas a baby?’, then filming in Africa), we can make sense of her pacifist stance.

Deveson has made her quest for peace a personal one. There is no shortage of emotive language or emphatic declarations, and they sometimes interrupt the flow of otherwise elegant and personal reflections. ‘Wars kill, full stop’, she writes, in reference to the ongoing civilian casualties in Afghanistan. She recounts the protests that were held when it was announced that the ‘Coalition of the Willing’ would invade Iraq, and reflects on the nature of conflict. ‘Young men and women seldom march off to war of their own accord … it is the lambs that go to the slaughter, rarely the wolves,’ she writes. Reasonable pay and ‘promises of glory’ are just some of the inducements. Both of these things, of course, appeal to human instinct.

Deveson’s in-depth exploration of human nature draws on science, psychoanalysis, and more. For instance, Einstein’s exchange with Freud during World War I gives Deveson pause for thought: ‘Is it possible to control man’s mental evolution … to make him proof against the psychoses of hate and destructiveness?’ Years later, Deveson is holidaying in Thailand, ruminating on human nature. The myths that have ‘perpetuated and glorified war’ persist: that ‘war is the norm … that man is a killer by nature and wars are a manifestation of human instinct, offering man’s finest hour, an opportunity for nobility and glory’. She laments not asking her brother, a ‘pink-faced officer cadet’ at nineteen, who fought in the conflict in Somalia and Sudan, how he felt about it. It is a discussion that is difficult to have not only privately, but publicly.

Deveson also interrogates human nature by looking at our primate ancestors. Chimps, our closest relatives (we share ninety-eight per cent of their DNA), participate in all manner of murders, cannibalism, and group violence. Instead, pacifists would do well to study the case of the bonobo, a species of ape that ‘respects hierarchies … resolves conflict, yet they are also social, share food, share sex’. Clearly, we are – like our primate cousins – capable of empathy and violence. Like any animal, ecological settings are crucial in determining our behaviour.

What hope do we have for peace if people believe in the inevitability of war? Can one exist without the other? Baruch Spinoza, who is quoted by Deveson several times, wrote that peace is ‘not an absence of war, it is a virtue … a disposition for benevolence, confidence, justice’. This outlook informs Deveson’s concept of a peaceful world, which is seen as within the realm of the possible, but is constantly jeopardised by political hubris and a lack of ‘responsible leadership’: leaders who refuse to negotiate, or even to meet.

Indeed, politics and vested interests may prove the biggest obstacle towards the creation of a truly peaceful world. Deveson argues that ‘war and violence are not life [but] events, grotesque and brutal’, and that peace is a way of life. Her (and Caldicott’s) overarching optimism is admirable – that cannot be faulted. But achieving peace – with countries, with the environment, or with other people – requires resistance to what has become the global status quo; it requires an imagination that transcends policy-making. Some fifty-odd years after Eisenhower’s farewell speech, war has become a trillion-dollar enterprise, haemorrhaging lives and dollars. We have yet to see a government with the conviction to formulate an exit strategy.

Comments powered by CComment