- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

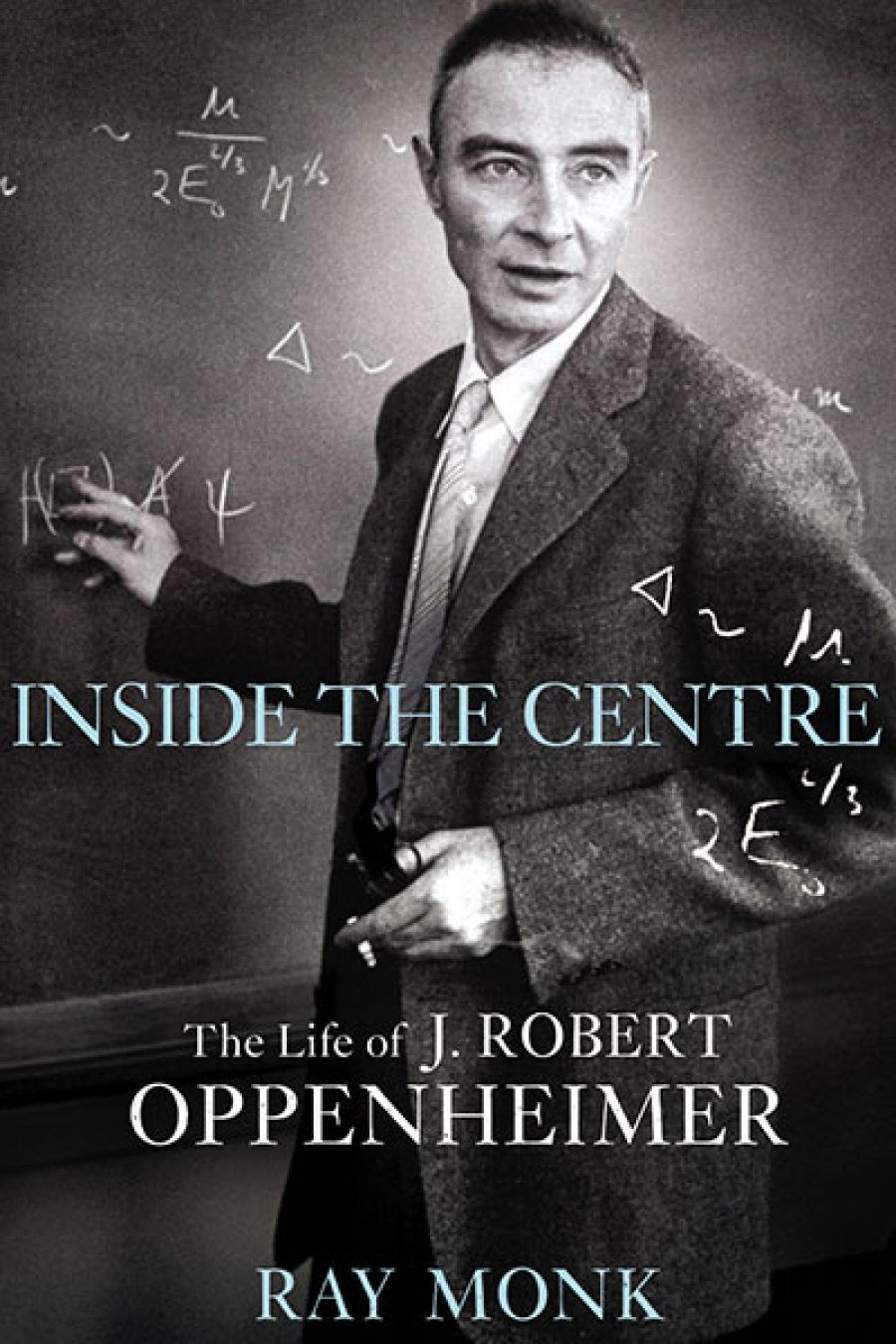

- Custom Article Title: Harry Oldmeadow reviews 'Inside the Centre: The life of J. Robert Oppenheimer' by Ray Monk

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Father of the bomb

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of Ray Monk’s biography of Robert Oppenheimer plays on several ‘centres’: the entrancing interior of the atom wherein physicists found the secrets of nuclear energy; the institutional centres of American intellectual life that served as Oppenheimer’s professional milieu; the seductive hubs of political power to which he felt a fatal attraction; his own inner life, full of strange shadows and paradoxes.

- Book 1 Title: Inside the Centre

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $65 hb, 832 pp

By the late 1940s, so well known was Oppenheimer in America that the popular magazine Physics Today could represent him on its cover by no more than a pork-pie hat. Even today, half a century and more later, almost everyone knows something about ‘the Father of the Bomb’: his pivotal role as head of the Manhattan Project and scientific director of the Los Alamos Laboratory; his now well-known allusions to the Bhagavad Gita, triggered by the Trinity test at Alamogordo; the postwar disagreements with Edward Teller about the H-bomb and his torment over a possible nuclear Armageddon; his early dalliance with communism, which was later seized on by the guard dogs of American ‘security’ (McCarthyite politicians, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, opportunistic careerists in the academy, sabre-rattling generals, and others of similar ilk).

A burgeoning literature has accumulated around both the nuclear arms program inaugurated by the Manhattan Project and Oppenheimer’s life and work: the major landmarks include Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atom Bomb (1986) and Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (1995), Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005), and Oppenheimer: The Tragic Intellect (2006), by Charles Thorpe. Monk’s avowed purpose is to remedy a conspicuous lacuna in this ever-proliferating body of writings, namely the absence of a detailed examination of Oppenheimer’s career as a physicist. In any case, says Monk, the man cannot be fully understood in isolation from his work.

Ray Monk’s track record is impressive. He has produced celebrated biographies of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1991) and Bertrand Russell (two volumes, 1996–2001), each rooted in prodigious research, shaped by a dispassionate approach, written in lucid prose, and informed by a sharp eye for the suggestive detail and the telling anecdote. As a biographer, Monk knows well how to contextualise his subject, construct a narrative, and throw into sharp relief the contours of a life. He also, in the main, keeps out of the way, eschewing too much editorialising and crediting readers with enough intelligence to make their own judgements and discriminations. As Monk signals in his preface, the biography spotlights Oppenheimer’s professional life as a physicist and academic. This entails some lengthy excursions into the arcane world of sub-atomic physics and a painstaking exposition of the work of a glittering constellation of scientists with whom Oppenheimer developed close professional and personal ties. We meet, among others, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Max Born, Paul Dirac, Hans Bethe, Ernest Lawrence, Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller, Julian Schwinger, and Richard Feynman – a veritable roll call of the century’s most eminent physicists.

Robert Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein

Robert Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein

Monk certainly realises one of his governing purposes through a detailed mapping of Oppenheimer’s contribution to modern science. This is no small accomplishment. He also tells us everything we might want to know about Oppenheimer’s unique contribution to the Manhattan Project and about his life as a public intellectual (terrain pretty thoroughly worked over in previous biographies). Always informed, sober, and thoughtful, our biographer addresses ‘Oppenheimer’s place in history, his impact on American society, and that society’s impact on him’. He carefully tracks a path through the Kafkaesque labyrinths of McCarthyite politics in the early 1950s and provides a nuanced account of Oppenheimer’s unhappy involvements with the security establishment – a murky story from which no one emerges with much credit. No question, Monk’s achievement in these respects is formidable indeed and should be warmly applauded.

However, in his preface Monk also says this: ‘what most interests me is Oppenheimer himself, his extraordinary intellectual powers, his emotional and psychological complexity and his curious mixture of strengths and weaknesses in dealing with other people.’ Compared to the task of unravelling this ‘psychological complexity’, the world of sub-atomic physics is mere child’s play. Oppenheimer’s personality was, to say the least, enigmatic, his motivations opaque, his behaviour occasionally bizarre, often unfathomable. Monk certainly uncovers some persistent motifs, which go part way to solving the many riddles of Oppenheimer’s life: his detachment from his Jewish heritage; his intense patriotism and fervent commitment to an idea of America; his addiction to work and determination to always be the Main Man; his apparent incapacity for familial intimacy; his attraction to the austere beauty of the New Mexico desert; his vague but potent spiritual yearnings. But while Monk avows an interest in the whole man, there are many aspects of Oppenheimer’s experience in which the biographer evinces not the smallest interest. This could perhaps be partly justified by the fact, accented by Monk, that many of Oppenheimer’s previous biographers have focused on the personal and/or political aspects of his life to the neglect of his work as a physicist. But faced with a door-stop biography of more than eight hundred pages, and given Monk’s stated interest in the man, the reader is surely entitled to expect a much fuller account of Oppenheimer’s emotional life and of his family relationships.

The friendship with his brother Frank is given detailed consideration, but about Oppenheimer’s love affairs, marriage, closest friendships, or troubled relations with his children we learn little or nothing. Nor are Oppenheimer’s deep interests in literature and Eastern philosophy given more than cursory attention. Oppenheimer is a perplexing and elusive subject, and one certainly does not want one of those impertinent attempts at a glib ‘psycho-analysis’ that litter much contemporary biography – but still! Despite the massive accumulation of detail in Monk’s biography, we arrive at the end with many questions unanswered and with only a fugitive sense of the flesh-and-blood person.

Another thing: the treatment of a raft of moral and intellectual questions in which one might have supposed that Monk, as a professional philosopher, would have a serious interest. Was the Manhattan Project, and indeed, modern science as a whole, a Faustian bargain bound to yield a bitter and malignant harvest? Did Dostoevsky indeed portend the future when he claimed that ‘without God, everything is permitted?’ What dark impulses fuelled an enterprise hitherto justified by the need to beat the Nazis to the bomb once it was clear, well before the end of the European war, that Germany’s nuclear weapons program was no more than a faint gleam in Werner Heisenberg’s mind? May we not see some connections between the instrumentalist rationality of the Enlightenment and the barbarities of the twentieth century – not only Hiroshima but Auschwitz, Dresden, Chernobyl, and Bhopal as well? Must not scientism – the triumphalist ideology of modern science, which acknowledges no authority outside itself and of which Oppenheimer himself was a fervent apostle – be held to account for the sins of Frankenstein’s children? Monk either skirts around or gives no more than a token nod to these vexing questions. Perhaps we should not expect more from an analytic philosopher. Impressive though it is in many respects, Inside the Centre is something of a disappointment.

Comments powered by CComment